Ahead of this year's Religious Education Congress, Angelus News heard from three featured speakers. This is the last of the three-part series. You can read interviews with Bishop Daniel Flores and Julianne Stanz here.

For Timothy O’Malley, Ph.D., this year’s stop at the Religious Education Congress is just one stop in the busy schedule of a very busy theology professor.

A native of Tennessee, O’Malley researches and teaches at the University of Notre Dame in South Bend, Indiana, in the areas of liturgical-sacramental theology, marriage and family, catechesis, and spirituality. He also works as the director of education at the McGrath Institute for Church Life and academic director of the Notre Dame Center for Liturgy.

He has written books and gives frequent talks on a wide range of subjects. Just days before coming to LA for the congress, he visited Ireland and Scotland for speaking engagements. Angelus caught up with him to discuss how he sees the Church responding to the biggest challenges in evangelizing today’s world.

Tell us a little bit about how you first ended up speaking at the congress, and why you’re back this year.

Last year, I was invited to speak at the congress through my relationship with Our Sunday Visitor. I spoke on young adults and the liturgy, how liturgical formation might enable young adults to develop a form of life dedicated to human flourishing. For me, coming to the congress is always an opportunity for learning.

My institute at Notre Dame, the McGrath Institute for Church Life, describes itself as a bridge that connects the academy and the Church. If that bridge is to function well, we need to bring the concerns of the Church back to the academy, reflecting on pastoral needs from those involved in pastoral work. The congress is the best place to do this kind of bridge-building in the Church today.

In a book review for America magazine last November, you wrote about the post-Vatican II “tide of disaffiliation” and secularism, saying that “it is possible … that it is the post-conciliar Church alone that will have the resources to respond to the real crisis, the one that the council fathers could not have recognized.”

In your view, what is the “real crisis,” and what should U.S. Catholics in 2020 be focusing on most when it comes to evangelization?

The crisis for U.S. Catholics today is twofold. It’s not secularization as it has often been presented by sociologists, as a kind of disenchantment. Human beings remain enchanted but just by the wrong things. They’re enchanted by money, by advertising, by violence and addiction.

The second dimension of the crisis is a loss of faith in institutions. Certainly, the Church has lost institutional credibility over the last 20 years, particularly around the sexual abuse crisis. But, U.S. citizens seem to distrust a variety of institutions: colleges and universities, the government, newspapers, and the media as a whole.

The Church today has the capacity to respond to both crises. We offer something to worship outside of the gods of mammon, of Instagram influencers, and drug use. At the same time, the Church is not another bureaucratic institution.

It’s a place where new charisms arise, where the Spirit flows through Christ’s body. These charisms take shape in the institution of the Church, becoming a concrete way of “gospelizing” the world.

That’s the heart of evangelization: It’s not just inviting your neighbor to go to Mass (that is, a very good thing, of course). Evangelizing is creating a culture where divine love is the meaning of life.

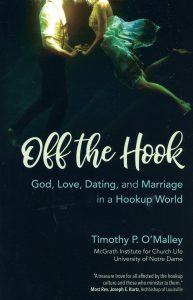

You’ve written and spoken quite a bit about “hookup culture.” In fact, you’ll be speaking about it at this year’s congress. How do young people you meet at Notre Dame and elsewhere react when you discuss such a potentially “icky” subject?

For the most part, no one likes hookup culture. This is because hookup culture is ultimately not about sex per se, but about a loss of communion, a fear of intimacy with another person.

People engage in noncommitted sexual encounters because they’re afraid to commit to a concrete relationship with another person, one that unfolds over the course of time. They want intimacy, but they’ve been formed to be terrified by the mundaneness of commitment.

Yet, that’s what we’re made for: communion with God and with one another. Once you give young people a space to talk about what they don’t like about hookup culture, to be critical of it, they find new possibilities for human relationships. It’s why my class at Notre Dame that addresses hookup culture directly has grown to nearly 300 undergraduates.

You teach, speak, and write about Christian marriage often. How does being married (with children) help inform what you have to say on the subject?

My marriage and my family are everything to me. For my students at Notre Dame in particular, it’s important to me that they know that my primary vocation is to be a husband to my wife and father to my children.

When we study the history of marriage and family, I want them to see this history not as some archaic past but as offering them wisdom even today. For this reason, my life is always part of what I propose to the students, the ultimate hypothesis that I give them.

I want them to see that the theology of marriage and the family we’re studying is salvific not just in the abstract but in my particular life.

In this year’s election cycle, many Catholics seem to be fretting about their “political homelessness,” a subject you’ve written about in the past. What’s your first piece of advice to Catholics feeling confused, dismayed, or better said, “homeless” during the election cycle?

My doctoral work was related to St. Augustine of Hippo. His famous quote, “Our heart is restless until it rests in you, O God,” is often evoked by those speaking about the spiritual life. But it’s also true for Catholic engagement with politics.

The temptation of the current political climate in the United States is to put our ultimate hope in a platform of a particular political party. For the Catholic, this is absurd.

Politics is not salvation, and elections are not sacraments. Catholics are, for this reason, politically homeless because our homeland is life with God, love unto the end. We engage in the political realm with this ultimate end in mind.

The Catholic vote should be highly confusing to our polarized age, defending the life of the unborn, the flourishing of the migrant who comes to our borders, the man sentenced to death, and the elderly whose life is not valued. This is the kind of politics that won’t always result in wins. But we order ourselves to the logic of the cross, rather than the data suggested by polling.