As the passengers of bus nine from Brownsville disembarked at St. Anthony’s Croatian Catholic Church in Chinatown, there was the usual mix of emotions; some happy to see relatives there to meet them, others confused or suspicious of the strangers moving toward them.

That was understandable, since it was strangers who placed them on the bus in Texas on Aug. 20, sending them on a near-30-hour trek to Los Angeles where they arrived on Aug. 21.

But the people who met them at St. Anthony’s — mostly affiliated with either the Archdiocese of Los Angeles or the Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights (CHIRLA) — were welcoming, offering food, clothing and, in one case, balloons and flowers.

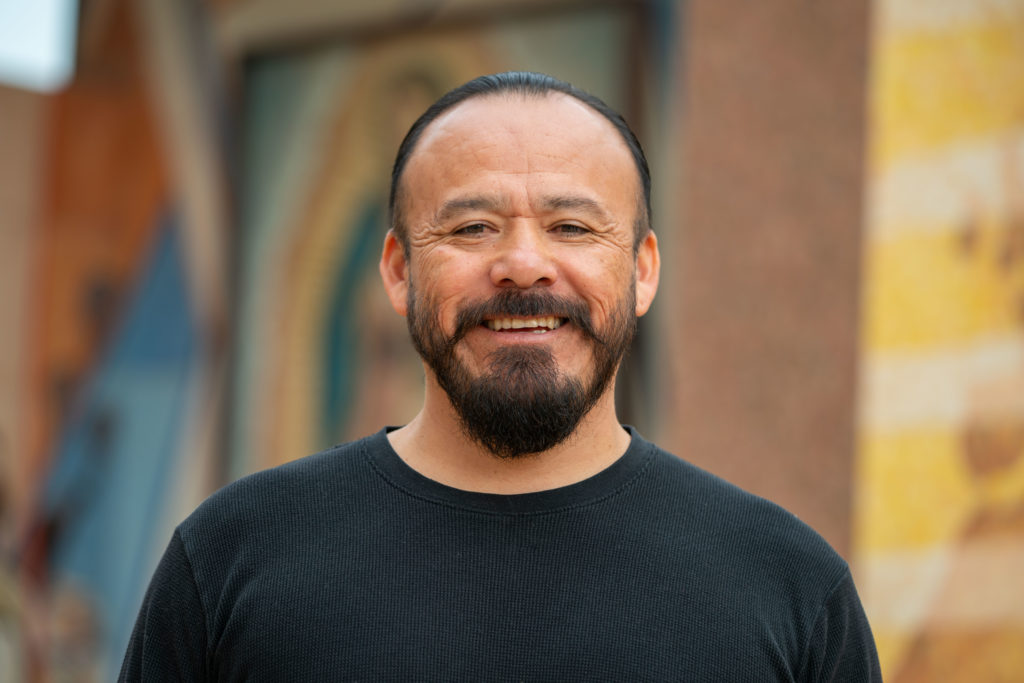

The bearer of both balloons and flowers was Filiberto Cortez, or rather, Father Filiberto Cortez, a fact lost on many that evening. After all, that particular day was the priest’s day off, and he wasn’t wearing his usual Roman collar. Instead, “Father Fili,” as he’s known among his brother priests, was wearing his civilian duds and looked very much like “a guy who was going to a Dodger game,” recalled Yannina Diaz of the archdiocese’s media relations team.

When Isaac Cuevas, of the archdiocese’s Office of Life, Justice, and Peace, saw “a youngish, fit guy with a good head of hair,” moving single-mindedly toward a young mother and her 3-week-old infant daughter, he assumed he was either husband or fiancé making “a grand gesture.”

Diaz said she and others around her had already begun to speculate what was about to happen.

“I mean, he’s holding this ginormous balloon in the shape of a heart that says ‘I Love You’ along with flowers. We were all looking and saying, ‘Are we going to have a proposal?’ ”

What was happening, of course, is what Cuevas called “a sweet act of simple kindness.” Cortez said that when he found out there was a young mother traveling alone with such a young infant, he felt compelled to do something to “let her know we are joyful for her and her child.”

The balloons, he said, were for the child, the flowers for the mother. When the mother finally processed what was happening — yes, she too was initially thrown by what Cortez was wearing — he said she told him, “I’m a single mother, I’ve done all this for her,” pointing at her daughter.

“She was in tears about this little gesture,” said Cortez. “I think it meant so much to her because these people have been made to feel as if no one cares about or wants them around. Seeing her reaction completely brought to mind what Jesus said about ‘I was a foreigner and you took me in.’ ”

Cortez knew about the young mother because the group that meets the buses has become “a very efficient operation,” said Jorge-Mario Cabrera of CHIRLA. “At most, we get 24 hours notice that the buses are coming. We’ve gotten very good at quickly making arrangements to meet them at schools or houses of worship. Those are human beings coming on those buses, brothers and sisters, moms and dads, and we want them to know that there are human beings here for them who they can trust.”

It is not Texas state officials who tell them of the bus departures; instead the information comes from contacts the consortium has developed in Texas, contacts who not only tell them when buses are leaving but who is on them. Bus nine contained 37 people, including 16 families with 14 children, the youngest of which was 3 weeks old.

There is, of course, always special concern when children are on the buses — and they usually are. That concern was ramped up this time since bus nine was headed toward Southern California just as Hurricane Hilary was. Also, less than two weeks before, a 3-year-old child had died on a bus en route from Texas to Chicago.

“A trip like that is hard on anyone, let alone a child, let alone a 3-week-old baby,” Diaz said.

Diaz said she could see the exhaustion in the young mother as she tried to eat with one hand and hold her baby with the other.

“I went up to her and asked if I could hold her baby while she ate,” Diaz said. “She told me the other women on the bus had held the baby for her as well, so she could rest. She was so young, it broke my heart when I found out she was alone.”

Upon learning that information himself, Cortez immediately began calling around to see if he could arrange for someone to take the young woman and her child in. Eventually, he did.

“It’s impossible to see that child and her mother and not think of Mother Mary,” Cortez said. “I mean, that was Mary and I’m not talking about a story, this was real, this was happening right now, a call from God to act.”

It is a call to action that brings many to meet the buses time after time. A call to action that, no matter what one is wearing, can at times be heartbreaking though ultimately soul-nourishing.

“I can tell you, when I see these immigrants each time getting off the bus, I see Jesus coming to us,” Cortez said. “And, again, I’m not talking about metaphors or symbols, I mean Jesus is literally there. I’ve never had a feeling, an epiphany like this, to feel what the saints must have felt, to serve Jesus, to recognize it is him you are receiving.”