Most 11-year-olds going to Mass with their moms don’t have a line of TV cameras waiting for them in front of the church. Nor do they have to worry about whether their wireless microphone is fitted properly, or if they’ll remember what to say in front of more than 3,000 people.

But neither have the average 11-year-olds living in the United States ever had to worry about crossing hundreds of miles of hostile terrain alone, without their families, personal belongings or any kind of guarantee that they’ll make it alive just to see their mothers again.

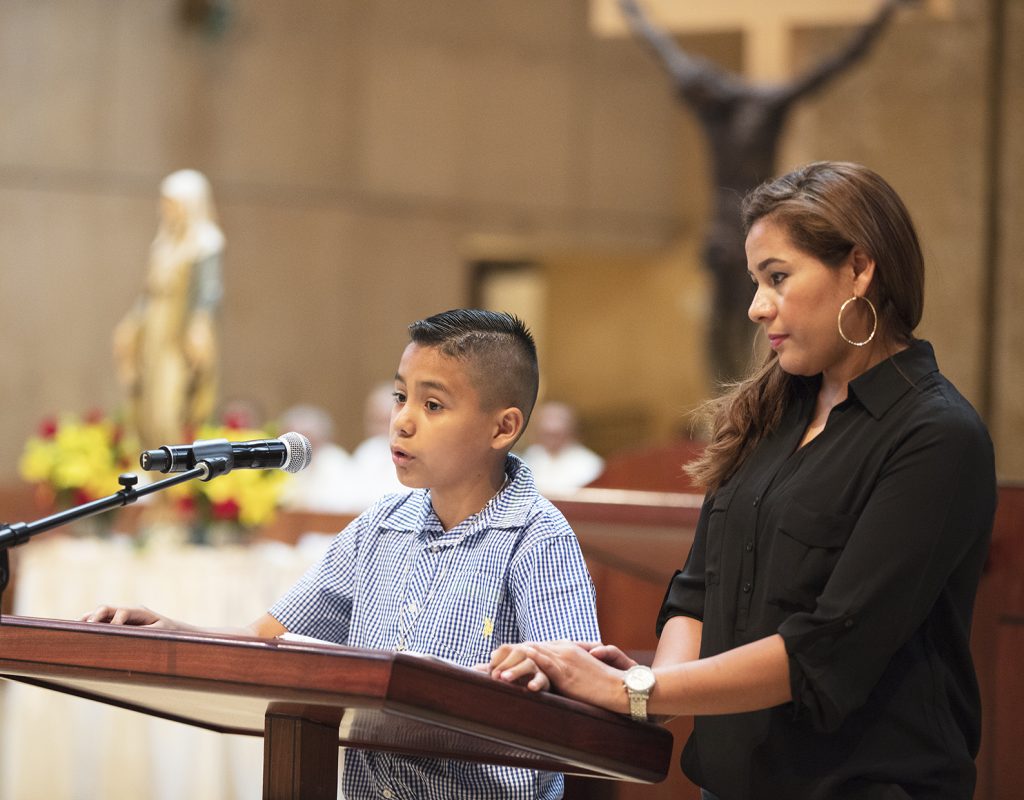

So for Adán, his speaking assignment — sharing his experience before the start of the June 24 Mass for All Immigrants at the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels — was nerve-racking, for sure, but nothing he couldn’t handle.

“I felt nervous,” the incoming sixth-grader told Angelus News after the Mass presided by Archbishop José H. Gomez and also attended by bishops and lay representatives from the Dioceses of Orange and San Bernardino.

“But I felt happiness at the same time to be telling so many people, to make my story a little known, at least here in Los Angeles.”

In the days leading up to the Mass, Adán’s story made the rounds on several local Los Angeles TV stations, the same week that the national outcry over the Trump administration’s “zero-tolerance” policy of detaining the parents and children of families became so loud that the president himself reversed it by signing an executive order ending the practice.

Adán’s experience is different. According to his mother, Roxana, she decided to flee El Salvador for the U.S. after the boy’s father became so violent that she began to fear for her life. Adán was only 8 months old.

“His father didn’t admit his paternity, so when I was pregnant he would come to my house to beat me,” Roxana told Angelus News. “He beat me and forced the doors until he managed to get in.”

Her infant son was also subjected to his beatings, Roxana said.

Years later, Adán decided he wanted to join his mother in the U.S. At 7 years old, he traveled north from El Salvador with a group of 50 people, many of them children, but was sent back home by immigration officials in a plane.

He tried again in 2015, but this time the person Roxana and other family members had paid to accompany Adán’s group disappeared with their money. He returned home again.

The third time, he made it as far as the Rio Grande, where he was detained by immigration officers as soon as he made it across to the Texas side. He stayed in a detention shelter for a month before federal officials put him on a plane to Los Angeles to be reunited with his mother.

“Thanks be to God I made it here,” Adán said after the Mass. “May he bless us here, inside and outside of the church.”

A broken system

The stories from America’s southern border usually sound like more of the same: Children trying to reach the border only to be detained or sent back; undocumented criminals being deported only to return again.

In extreme cases, entire families have been found half-dead from heat exhaustion in the desert shared by the southern U.S. and Mexico. Cartels use caravans of migrants to smuggle drugs into the U.S., where more than ever before Americans are addicted to opioids sent from Mexico.

All are consequences of a broken immigration system that advocates have been complaining about long before the election of President Donald Trump.

And long before disturbing images like those of children separated from their parents living in a former Walmart in Texas emerged earlier this month in news reports, politicians from both sides of the aisle have struggled to pass any kind of substantive immigration reform legislation.

“The biggest thing standing in the way are the politicians,” said Isaac Cuevas, associate director of the Archdiocese of Los Angeles’ Office of Immigration Affairs.

“They need to set aside partisan issues and understand the importance of coming up with a compromise. At stake are the millions of people who are here and the hundreds of thousands of people around the world coming here seeking help.”

Proposals such as opening a pathway to citizenship for law-abiding undocumented immigrants, especially for those brought to the U.S. as children by their parents, have been criticized as a form of “amnesty” by some lawmakers and especially by some commentators in the media.

“This injustice has been going on for a long time,” said Archbishop Gomez in his homily at the June 24 Mass, referring to the inability of Congress and the president to protect “Dreamers,” or recipients of the federal Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, from deportation as the program expires.

“It did not start with this administration. But it will not stop until good people end their silence and speak up for what is right.”

Also speaking at the Mass was Paulina Ruiz, a 26-year-old DACA recipient who came to the United States illegally at the age of 6 in need of treatment for cerebral palsy. She went on to graduate from UCLA.

‘Tough times’

“We are living in tough times,” said Ruiz, speaking from her wheelchair before the Mass. “My story has reached many, and I have the duty to stand here with all of you today to ask you to protect our immigrant community.”

The Mass was the culmination of a novena (nine days of prayer and reflection) at parishes throughout the archdiocese, and a three-day, 60-mile walking pilgrimage by a group of faithful from Lake Forest to the cathedral in solidarity with migrants.

Following the Mass, the faithful venerated the relics of St. Junípero Serra, St. Frances Xavier Cabrini and St. Toribio Romo, all recognized as patrons of immigrants.

But like Adán’s story, the novena, pilgrimage and liturgy took on a more special meaning in light of the news headlines describing the plight of children deliberately separated by federal authorities at the southern border.

Those orders came from Attorney General Jeff Sessions, who in defending the policy cited “the clear and wise command” of St. Paul to the Romans, “to obey the laws of the government because God has ordained them for the purpose of order.”

Although President Trump has since signed an executive order undoing parts of the policy, the order does not address reuniting the more than 2,000 separated children with their parents.

And as Archbishop Gomez noted in his homily with alarm and disbelief, the government has no idea when the families might be reunited.

At the Mass, some immigrants told Angelus News that things are not the same as when they first arrived.

“It’s nice here, but now with the immigration situation, everything’s changed,” said Cristian Posada, who attends Our Lady of Perpetual Help Church in Newhall with his wife and three children.

Posada immigrated to the U.S. from Mexico with his wife, Leonor, 15 years ago.

“You no longer feel safe here because every day that passes, you wonder if you’re going to come across the immigration officers and be deported,” he said after the Mass.

Asked if he’d tried to apply for legal status since migrating, Posada said that the legal obstacles were too discouraging.

“There’s no opportunity, because if you try to apply [for legal papers], you can make a mistake and get deported. There’s no way, there’s no assurance.”

Moments earlier, Archbishop Gomez had voiced similar frustration as he led prayers for the political leaders charged with confronting the country’s deepening immigration crisis.

“For years now, we have been asking our leaders to fix our broken immigration system. Year after year, they keep telling us, ‘Ma√±ana, ma√±ana,’ ” he said.

“We need to tell our leaders — no more ‘ma√±anas,’ no more excuses,” he said, using a line that was answered with applause more than once inside the cathedral. “The time is now.”

A so-called “fix” to the system has eluded recent U.S. presidents, despite efforts to pass reform that strengthens security measures at the southern border while addressing the status of millions of tax-paying, law-abiding undocumented immigrants with no plans to return to their native countries.

Prospects for their fate have suffered since the election of Trump, whose anti-immigrant rhetoric during the 2016 presidential campaign capitalized on the fears and frustration of many Americans who felt that the government was giving a free pass to Latino immigrants who migrated here illegally, while not doing enough to “Make America Great Again.”

Still, Archbishop Gomez and his fellow U.S. bishops hope that compromise legislation like “the USA Act” in Congress could help break the impasse. The bill would permanently protect “Dreamers” such as Ruiz from deportation and provide them a path to citizenship, while improving border security and addressing the root causes of instability in countries like El Salvador.

But families worshipping at the cathedral on June 24 remain optimistic.

“We don’t want to do any harm,” stressed Adán, who said he wants to be a police officer when he grows up. “We came to this country to be the best we can be.”

“It’s true that many are forced to pay for the deeds of a few, but the great majority come here just to work to earn bread for our children,” added his mother.

“The only thing I can ask of people in the same situation as us is that they fight and try every day to be better people, and to show it not only with words but with their example: that we deserve to live in this country.”

Interested in more? Subscribe to Angelus News to get daily articles sent to your inbox.