In the spring of 1992, then-Father David O’Connell was comfortable in parish life in south LA. The Irish-born priest had served the Archdiocese of Los Angeles for more than a decade by then, and he was familiar with the conflicts and tensions that existed in the area.

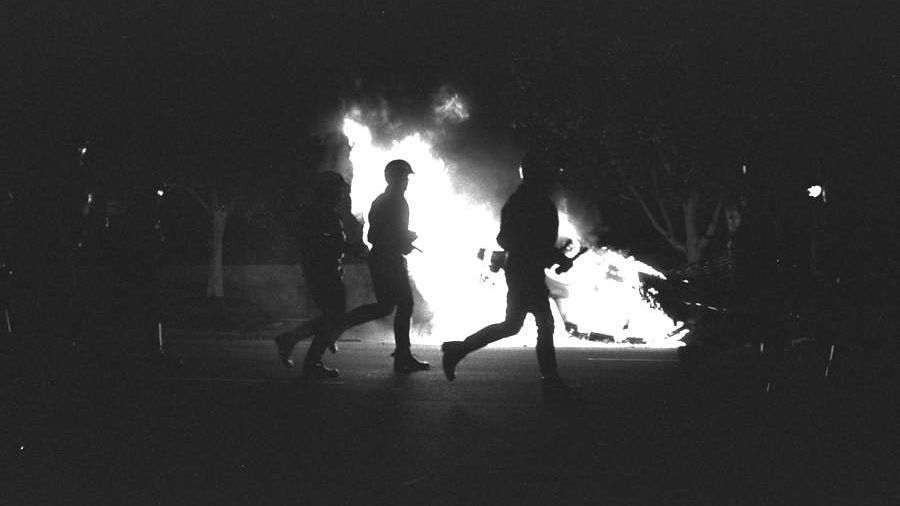

But O’Connell wasn’t ready for the riots that would break out on April 26, 1992, after the acquittal of four police officers who had been videotaped beating an unarmed black man, Rodney King.

O’Connell – who is now an auxiliary bishop in the Archdiocese of Los Angeles – was pastor at St. Frances Cabrini Parish when the 1992 riots took place. More than 60 people were killed in the violence, with over 2,000 more injured, and $1 billion of property damaged.

O’Connell told CNA that when the riots began, he was actually in Washington, D.C., where he was testifying before a Congressional committee on violence in urban America. He said he turned on the TV at his motel and saw footage of a restaurant being attacked, just blocks from his parish back home.

When he flew home the next day, O’Connell said his plane had to be rerouted because of concerns about people shooting at airplanes landing at LAX.

By the time he arrived home, he found widespread destruction. “There was a huge devastation of businesses – large ones, small ones, burnt to the ground,” he said.

O’Connell reached out to local Catholic, Baptist, and Muslim leaders, to start a conversation and to pray together while waiting for the nightly riots to calm down.

He also helped in local clean-up efforts. He said that work was mostly cosmetic, but he viewed it as a symbolic gesture “to show that we were going to come out of it.”

While he was still trying to assess the damage and process the trauma of the unfolding events, he also started thinking about ways to begin reconciliation in the community.

“Right away, we said that our churches were open for people, if they had taken stuff, to bring it back,” he said.

The idea worked. Some people involved in the looting later regretted their role in the riots.

“People brought things back, and we tried to give them to the stores which they had come from,” O’Connell said.

About a year before the 1992 riots, O’Connell had been involved in initiatives to build trust between the local community and the police. But the efforts had not made much progress.

In the months that followed the riots, however, O’Connell realized he needed to focus on those efforts if the community was ever to heal. He and other local faith leaders held meetings with sheriffs and members of the LAPD in people’s homes. At those meetings, police and civilians practiced talking to each another about their concerns and finding ways to disagree civilly.

“That was part of our work as a Church, to try to provide spaces for conversations,” he said. “And we thought we really had achieved a lot of progress. Killings were way down in south Los Angeles. There was a trust built up between LAPD and residents. This level of trust has helped us over many different crises over the last almost 30 years to be able to talk things through.”

Today, O’Connell fears that the killing of George Floyd and other recent incidents of police brutality have eroded much of the trust that had been established.

“This [Floyd’s killing] is so egregious, it’s just heartbreaking. It’s like the work that the community leaders have tried to do over the years is falling apart,” he said.

“For all those years we were doing this in the ‘90s, the early 2000s, we kept trying to convince people that we have to trust each other, you have to trust the police department, and convince the police how to deal with problems, de-escalate, respect people, build relationships so that when conflicts happen, they don’t result in violence, and you can deal with things in a more humane way, a decent way, a civil way,” he said.

“It’s harder now to go back and say, ‘Ok, we broke that trust, and now we want you to trust us again… it didn’t work last time, but trust us again next time’.”

O’Connell said he understands the anger of many communities in the wake of police brutality. Their suffering is real, and their anger justifiable, he said.

“People [in 1992] felt – and the African American population in particular felt – very grieved that they were able to do this and there were no repercussions for the officers involved,” the bishop said, adding that he sees similar sentiments today.

However, he said, if he could share one message with people rioting, it would be that dialogue, not violence, is the best way to solve underlying problems.

“I know it’s hard for them to hear right now, but violence is never the answer,” he said.

“It doesn’t seem so right now, but if we can do the work of negotiation and politics and building trust, we can achieve a lot more good out of that than we can out of any violence.”

The process of reconciliation in communities will undoubtedly be a long and difficult one, the bishop acknowledged.

“But we have to do it. It has to be done,” he said. “There’s no other way forward than to try again as best we can…to try to build these conversations and maybe even this time, take it as a national project, not just a local project.”