For all the arms he’s lovingly twisted, every gut he’s jovially busted, for every alumnus’ wallet he affectionately pried open, there has always been an unspoken passion behind Msgr. Aidan Carroll’s methods.

Was it the buildings he’s built, the scholarships he’s funded, the ongoing financial stability he’s helped give his beloved Bishop Amat High School, from which he recently retired as president after 28 years?

Yes.

Then again, no.

What always guided the Irish priest is a simple, unwavering belief in the value of Catholic education. He’ll be happy to see the new, $11 million performing arts center he’s spent more than a decade building open on Bishop Amat’s campus this fall but, like everything else he’s done, he won’t see it as an end but a continuing means to the ultimate mission.

“What I have always tried to keep in focus is that the No. 1 reason that I’m here, what I feel is our purpose and achievement, is to bring our children up with an outstanding education permeated by the truth of the Gospel,” he said. “I make no secret that this is my primary purpose and I’m proud of having done that.”

Those are words spoken during a rare moment of seriousness for Msgr. Carroll, 82, known for his self-deprecatory humor. Dan O’Connell, who has worked with Msgr. Carroll during his last years as deputy superintendent for Catholic schools, considers him “an absolute legend,” precisely the kind of label the priest is known to reject.

Legendary? He’ll tell you he more closely identifies with a character he saw recently in a comic who surmised, “I’m at the point in my career where my problem-solving skills are being eclipsed by my problem-creating tendencies.”

There’s not a lick of truth in that, of course. Because of delays, including lost manpower hours due to COVID-19 (which he himself battled, and defeated) he delayed his retirement for years so that he could see the performing arts project through to the end.

“I’ll tell you, when it comes to his characteristics, his skills he — and I don’t use this word lightly — he’s a genius,” said Rick Beck, principal under Msgr. Carroll who will now replace him as president.

“He could have been a CEO and that is no exaggeration. He never had a deficit budget, [Bishop Amat] has always been in the black, he’s always managed to squirrel away some funds. In terms of how he operates, it’s always with a sense of humor and this easy way about him that makes you want to come to his side, to participate. That’s what the best leaders do.”

Arriving at Bishop Amat nearly 30 years ago, Msgr. Carroll found a school with, in his words, “shabby” facilities. The roof leaked, the library and gymnasium were worn out, and there was no air-conditioning, the latter forcing teachers to give students shortened days during the summer. One by one, he addressed those and many more, including less than glamorous fixes such as plumbing.

To ensure a Catholic education was possible for anyone in the working-class neighborhoods Bishop Amat’s La Puente campus serves, he began growing a scholarship program that matched alumni contributions. The program is worth more than $8 million and made attending a possibility for many families who believed it was out of their reach.

“Monsignor understands if there is no money, there is no mission,” said O’Connell. “Without money we can’t serve the Catholic mission. He not only understands that, but his keen business sense has meant he has raised more scholarship funds than any president of our schools.”

He’s done it by appealing to individual donors, preferably face-to-face.

“I’ll tell them, ‘My friend, do I have a deal for you.’ And I tell them about the scholarship and that they can name it to memorialize a loved one, perhaps a parent.”

Of course, he admits sometimes to playing on more base motivations, telling this former student that that former student has already contributed to the program and wouldn’t it be awkward at the next reunion to have to face them?

“This isn’t anything I was trained for,” he said with a laugh. “They don’t teach you that kind of stuff in the seminary.”

Paul Escala, Superintendent of Catholic Schools, says Carroll’s ability to raise funds comes from a realization that “it’s not about ‘The Ask,’ it’s about the relationship you have with the person you’re asking. It’s about trust, that has a value far beyond monetary means. When donors feel a strong connection, they want to be asked. He knows that, he knows the community and cultivates relationships, strong relationships. That’s why he’s the best at it.”

Still, Msgr. Carroll makes it clear he doesn’t want to be seen as “a money getter.” It’s certainly not how he sees himself, and certainly not what was on his mind when he came to the United States in the 1960s after graduating from Seminary of All Hallows in Dublin, Ireland. Back then he was convinced his path in America would lead him to parish life, and eventual retirement as a pastor.

Instead, he ended up as the only assistant to Msgr. Donald Montrose in the Archdiocese of Los Angeles’ Department of Catholic Schools for Secondary Education. He learned a lot from Msgr. Montrose, not the least of which was to be OK with taking some heat. “He used to say, ‘Principals are on the firing line, it’s our job to channel the hate down here,’ ” and that the best way to do that was with a bit of humor.

Not all the lessons were pleasant. Looking back on that turbulent time, Msgr. Carroll said he believes the Church began “losing contact with young people” amid social upheaval and violence home and abroad.

So when he left the archdiocesan offices to serve as a principal — first at St. Paul High School in Santa Fe Springs, then at Bishop Amat — he found himself looking to always bridge that gap and make as many connections with young people as often as possible. He tried to never pass a kid in the hall without saying hello to them by name. He attended as many events as possible, and notes how much a little gesture like showing up and sitting down can mean to a young person.

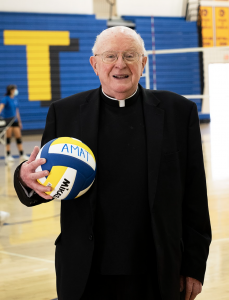

“If I show up at a volleyball game, the next day I’ll get so many kids saying, ‘Hey Monsignor, thanks for coming to our game.’ It means a lot to them, and that means a lot to me.”

But, by far his favorite method of connection would be by celebrating Mass with students, whether at morning services in the school chapel or at Masses attended by the entire student body.

“That is something I really looked forward to on a regular basis,” he said. “To have 1,200 teenagers sitting there, able to see the whites of my eyes, and they are serving and they are doing the readings. For many of these kids, their lives revolve around the school; that’s a huge opportunity I have.”

The connection continues long after students leave Bishop Amat. Choosing to support the school financially later on makes alumni still feel part of the school. It’s not unusual for students to ask Msgr. Carroll to perform weddings or funerals for a family member, something he says he feels “humbled by, that they would think of inviting me to do a special thing like that.”

He’ll have more time for that in retirement. He will continue to live at nearby St. Martha’s Church, about 15 minutes from Bishop Amat. Beck has told him that he is welcome on campus any time, “for any reason or no reason at all.” Msgr. Carroll says that beyond visiting family back in Ireland, he intends on taking Beck up on his offer: “I don’t want to go into a cave.”

That’s unlikely, given all the volleyball games to be played, all the kids to talk to, all the Masses to be celebrated.

“In my job, I have a lot of things to be concerned about,” Escala said. “I can tell you one thing I don’t lose any sleep over is Bishop Amat. Under Monsignor and now with Rick, who he has mentored, that school is in good hands. And that is all because of Msgr. Carroll. He’s our living endowment.”