Despite tough times in foster care, hope — and a Catholic education — are starting to pay off for Elizabeth Wolf

It’s been a ride — a blessed ride, for sure, for Elizabeth Wolf.

What are the odds of a girl from the projects, raised mostly in foster care homes, getting a full-ride scholarship to graduate from a private college on the east coast? Or then becoming a prestigious Fulbright Scholar, soon off to Spain to help teach English and, hopefully, work with refugees?

In Los Angeles County, only 58 percent of youths in foster care homes graduate from high school. Bouncing from school to school, many have academic problems and are passed off as having learning disabilities. Others who act out are often labeled with behavioral disorders.

For “Liz,” as her friends call her, the challenges were formidable. Foster care kids often don’t get the help they need to even finish high school.

And going off to a four-year college? Forget about it: only 3 percent graduate from college, according to statistics from the Alliance for Children’s Rights. And if they do, it’s often from community colleges.

But it gets even worse for foster kids.

Across the nation, even having more than one foster care placement raises a youth’s likelihood of becoming homeless by 1.5 times. In fact, within 18 months of being so-called “emancipated” from foster care, usually between the ages of 18 and 21, 40 to 50 percent are homeless.

In Los Angeles County, half end up either being homeless or incarcerated. And foster care teenage girls in Southern California are 2.5 times more likely to be pregnant by 19.

So how did Liz do it? How did she break away from those life-defining statistics?

A Catholic school start

It started in Las Vegas, where she was born 22 years ago. First living in government housing, “the projects,” and then a rented house. There were a lot of boyfriends in and out of that house. Many were drunk. She saw them beat up her mom.

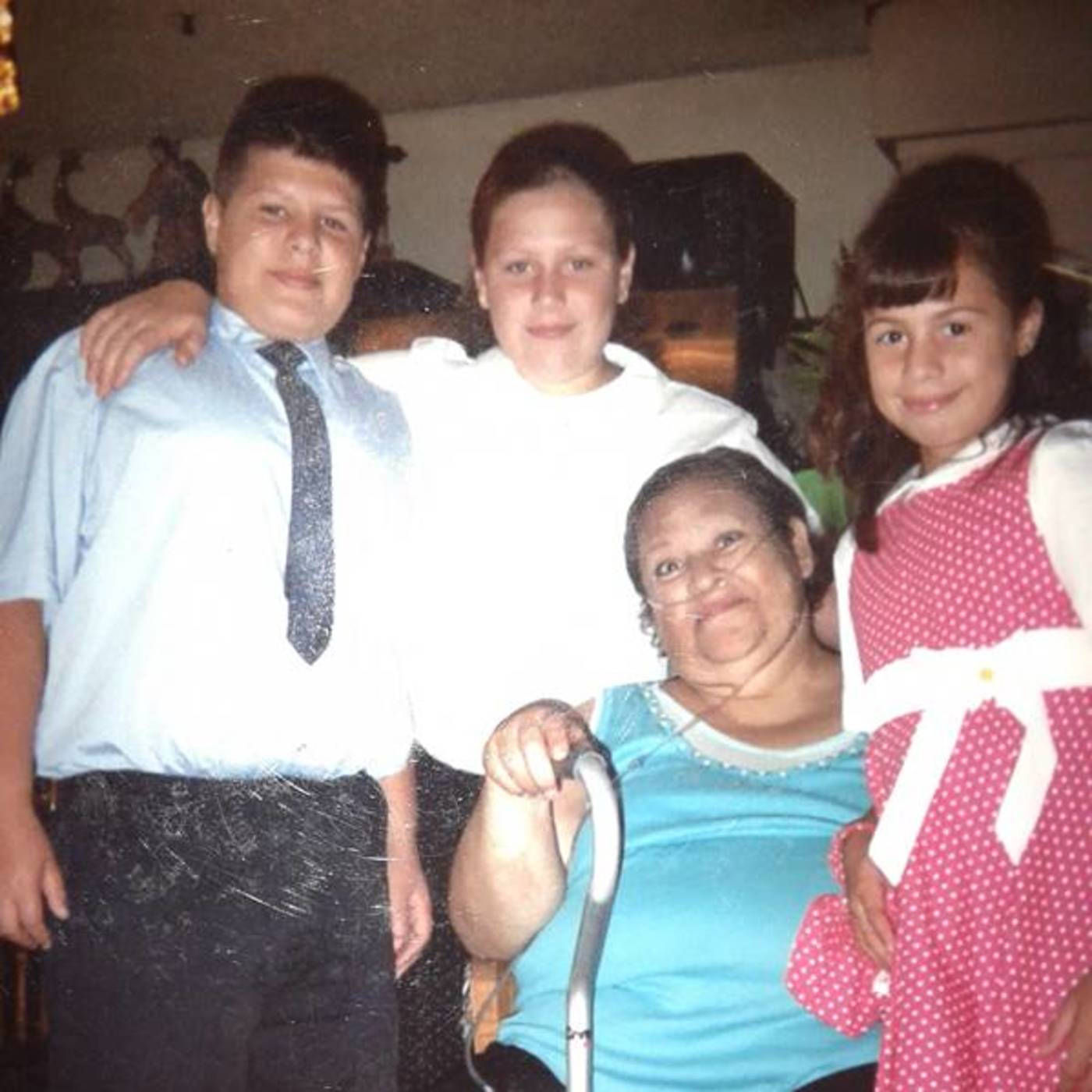

When she was in the fourth grade, her mother had a nervous breakdown. She and her older brother, Drake, and younger sister, Carolina, went to live with their grandmother. Later, when her mother wanted them back, her grandmother declared, “No! There’s no way you’re taking these kids.”

Then her grandmother, three kids in tow, moved back to the LA-area suburb of South Gate. She enrolled all of them in nearby St. Emydius School, to help make sure they would get a good education.

Two years later, when she died, the children went to live with their aunt, who couldn’t keep up with tuition. When Liz told the principal they would have to withdraw and go to public school, grants from the Catholic Education Foundation (CEF) and other financial aid for the three helped them stay and graduate from the parochial school.

“So that’s how we got a Catholic education,” Liz explained to Angelus News.

After graduating from St. Emydius, Liz and Carolina went on to St. Joseph High School in Lakewood, again with CEF grants and other financial help. Drake went to St. John Bosco High School in Bellflower.

“A lot of teachers and principals were looking out for me and my siblings,” she said, “and looking out for my family in general.”

But during the summer after her sophomore year at St. Joseph’s, her aunt was no longer eligible to care for the three kids.

So they went into foster care for the first time, the girls in one home, Drake in another. But that fall the siblings were reunited in another foster home — one Liz would come to dread.

Still, she said, “That lady, my foster care mother, I think God put her into my life for a reason. I learned a lot in that home, but it was very hard because I was used to taking care of me and my siblings. I’d grown up fast, and so I was very much their parents. I remember having fights with my foster mom. I didn’t like the way she was taking care of us.

“It wasn’t a healthy environment for me and I started to act out, and I started to do a lot of things. I just wasn’t prepared to be in that environment with that woman. She eventually walked into my school at St. Joseph’s and unenrolled us. She said we weren’t able to go to school there anymore.”

When her elementary school principal found out, she called the principal of another all-girls’ high school at the time, St. Matthias in Downey, and explained the dire situation to Principal Erick Rubalcava. He readily agreed Liz and Carolina should come to his high school, again, with the help of CEF grants and financial aid.

Blessings in disguise

All this was bittersweet for Liz.

“Mr. Rubalcava was so helpful,” she recalled. “So starting my junior year we started at St. Matthias. Again, I feel like it was a special blessing in disguise. I remember when she withdrew us from St. Joseph’s I was crying hysterically, because I didn’t know if I was going to be able to go back to get a Catholic education. I was very upset. It was like for my foster mom, this was a vindictive way of hurting me.”

After a moment, she added, “And again, I think it was a blessing in disguise because I felt more community and more at home at St. Matthias with more students like me.”

But her foster mother wasn’t finished. She kept telling Liz she would never be able to go away to a good four-year college. Perhaps a local community college, but that was it. After a while, Liz bought into having low expectations for her future, despite her good grades.

Things got worse when in November of her senior year at the school (by now the newly merged coed St. Pius X-St. Matthias Academy), her social worker gave her the seven-day notice from her foster care parent that every foster kid knew about: a notice stating that the parent no longer wanted to take care of them.

In a week, her foster mother would no longer be her foster mother.

Liz panicked: “My brother was 18, so he was able to emancipate into California’s Independent Living Program with his friend. But I was 17, and Carolina was 16. So we didn’t know where we were going to go. We didn’t know where they would place us. Would we be split up? It took over my mind day and night.”

Liz reached out to Alfredo Casada, a single parent of two adopted children and also a foster care parent.

“I went to him for advice and wound up asking him if he would foster me and my sister. And he said no problem. There was an empty room in his home.”

Casada’s house would end up being Liz’s last foster home. She credits him with mentoring her through applying for college scholarships, offering advice and even driving her to a second interview for the Posse scholarship, which offered to cover four years of college.

“He encouraged me to speak up, be clear and shake their hands,” she remembered.

“I really do believe it’s because of him that I got Posse,” she continued, “because my confidence before I met him was not there at all. Being in Alfredo’s home, he taught if there’s a ‘no’ and you want it to be a ‘yes,’ fight for it.”

Posse scholar

Liz, in fact, did became a Posse Scholar and went on to graduate last month from Dickerson College in Pennsylvania, where she majored in Spanish.

The experience was not always an easy one. It was her first time being separated from Carolina.

“That was so hard, you know, being here and also recognizing that back home she and my brother Drake were missing me.”

She also said the change from living in foster homes to dorming at a mostly white, affluent private college on the east coast was a “huge cultural shock.”

But her time at Dickerson also presented some opportunities that many foster children don’t get. A few weeks before graduation, she found out she’d been awarded a Fulbright grant to help teach English in Spain’s Canary Islands. She’ll also do a service project, hoping it will be working with refugees.

Why refugees?

“My sorority sister was talking to me about how bad the refugee crisis was right now, and so I was thinking about that,” she said. “Displaced communities, underprivileged communities was something I was always interested in. So that’s why I would like to work with the refugee population in Spain if I could.”

Drake recently graduated from Cal State Long Beach and is applying to join the California Highway Patrol. Carolina is still a student at Cal State Long Beach.

So, again, how did Liz and her siblings — all raised in foster care settings — accomplish so much so soon? How did this happen when so many foster kids, shuffled from one home to another in Los Angeles County, wind up on the street shortly after being emancipated?

Liz isn’t really sure herself how things have worked out so well. At times it still seems unreal that she’s a college graduate and now a Fulbright scholar soon to be off to Spain on another life adventure.

All she knows is that she wants to give back by working with foster kids — maybe as a social worker after she goes to graduate school or in some other capacity. She believes that’s where she will not only find her life’s fulfillment but also a genuine joy.

“Honestly, I think Catholic education saved my life,” she told Angelus News.

“I don’t know how to explain my life before St. Emydius and before coming to California. So many people helped me — from my grandmother to my vice-principal at St. Emydius, Ms. Ponce, to Mr. Rubalcava to Alfredo and Mary Rose Jeffry, who’s on the board at St. Pius X-St. Matthias Academy. She and her husband have just loved me unconditionally.

“I don’t think a lot of foster youths have had the opportunities that I have had. And I think that’s very unfortunate. But I am very, very grateful for the people that I’ve come in contact with,”she said.

“I think that God is definitely looking out for me and my siblings,” she added with a chuckle. “And I’ve made the most of what God has given me, which was a lot.”