Cindy, a fourth-grade teacher at a parochial school in East LA, likes to treat her students as equals. Both are on journeys of discovery and learning. Like studying how students in China have a different way of learning their multiplication tables — something she shaked her head at with a questioning smile, before showing me around her cozy classroom.

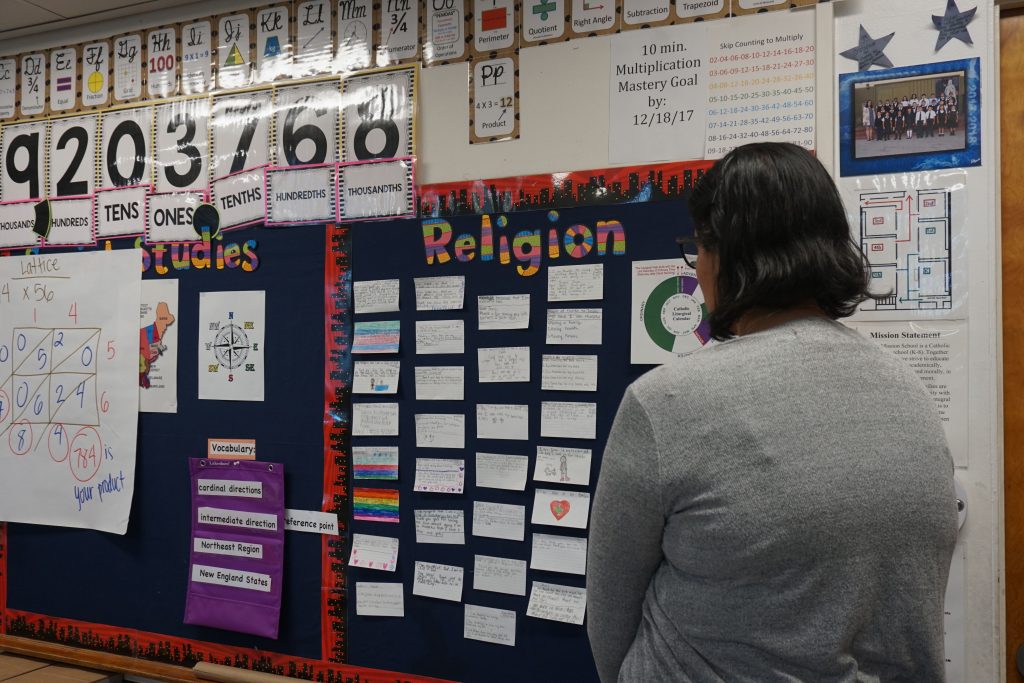

It’s an explosion of color, with walls virtually covered with religion and reading boards, phonics charts, a painting of Our Lady of Guadalupe and two long whiteboards.

But the 26-year-old educator also shared something else with some of her fourth-graders from East LA. Almost one-third of her 25 students were born in the United States to undocumented parents. And so was she.

“In sixth grade, I started at a new school, Immaculate Conception in the Pico-Union area of Los Angeles,” said Cindy (who didn’t want her last name or where she teaches identified to protect her still-undocumented parents).

“It was halfway through the school year when my dad got fired from his construction job when I found out after coming home from school.

“My mom told me. And I was scared. But I guess she was more concerned about ‘What are we gonna do now?’ My father never worried about [being deported] until after the Bush administration, when he lost his job.”

Cindy pushed herself to do her best in school, but not stand out. And like her mother, she put the family’s possible breakup in God’s hands. Still, she also realized, “ ‘Well, if nobody’s gonna help me and nobody’s gonna help my family, I have to do it.’ So I took it upon myself to grow up faster.”

The determined adolescent finished middle school, got good grades in high school and received scholarships and financial aid to graduate from the University of California, Riverside. She returned to Los Angeles to work at the nonprofit City Year Los Angeles program, mentoring third- and fourth-graders near Watts.

“After my last year of service at City Year, I realized ‘I’m ready for my own classroom,’ ” she said, sitting across from me on a plastic chair and group table-desk that’s definitely made for the younger set. “So I started applying.”

This is Cindy’s third year teaching fourth grade at the elementary school. She wanted to give back and feels blessed to be in a Catholic academic setting once again. She can see that children are being empowered, which she struggled so hard to do at City Year Los Angeles.

But there’s another, more personal, reason Cindy feels blessed: the special connection she has with students who are also U.S.-born with undocumented parents, children living with the ever-present fear their father or mother, or both, won’t be home one afternoon when they get home.

With the recent crackdowns targeting any immigrants lacking documentation — not just those with criminal backgrounds, as other presidential administrations have focused on — any undocumented individual or family can be arrested, detained for months before a hearing with an immigration judge and deported back to a country where they haven’t lived for decades.

“When I see students really worried about this, I tell them it’s OK, because I lived with that every day — and still do,” she said. “And I tell them what makes me forget about that problem is the fact that I’m coming here to help you.”

Then Cindy talked about a girl in her fourth-grade class last year. She found out on a late Friday afternoon that her mother had been detained.

“The first thing she said to me Monday morning was, ‘They caught my mom.’ And ever since then, I saw her shut down,” said the teacher. “She was keeping herself busy, but not with school work. It was just making things out of paper, distracting herself, I guess, just going back into a childlike state. She just didn’t want to deal with it.

“And already academically she was low. But you could tell that she was trying. And now in fifth grade, she still shuts down. Her attitude is still, ‘I don’t want this work.’ And she’s more aggressive with other kids. So she’s getting worse.”

This year is no different. Students continue to be stressed out. A boy is upset about what’s going to happen to his undocumented mom. Another has taken on his mom’s concern about finding the right lawyer to help her husband from being deported. These are just a couple troubling issues her students are dealing with.

rn

rn

rn

Hypervigilant kids

Luis Zayas, dean of the Steve Hicks School of Social Work at the University of Texas, Austin, calls his research and writing about U.S.-born children of undocumented immigrants as well as children and mom refugees in American detention centers “just a drop in the bucket.”

Before coming to academia full time, he worked as a social worker for more than 30 years. And today he works with lawyers in immigrant courts as an expert in the field, testifying about the harm it would do to these citizen children if their undocumented parents were deported.

“Probably what we found most — and it really confirms what mixed-status families know, whether they’re U.S.-born or have come to America at an early age — is they grow up with an ever-present fear,” he told me recently. “And that constant fear is that at any moment their parents, or themselves if they are undocumented, will be arrested, detained and deported.

“It’s just the dread of everyday life that most of us don’t have to live with,” he went on. “But these children do. Just about every knock on the door that’s not expected can stop their heart and sends them into some anxiety of who’s at the door. And just riding in cars, there’s always the fear of being pulled over. In one case, the parents were fearful of going pass any police station and fire station.”

That fear results in children being hypervigilant — making sure there’s no danger or threat nearby. He and his co-workers also found that many are exceptionally well-behaved and self-controlled, not wanting to draw any attention to their parents.

They also learned how the children quickly realize who they can talk to and confide in.

And there are serious consequences of having this ongoing stress, according to Zayas. The more of these so-called “adverse childhood experiences,” the more likely they are to develop mental disorders and chronic diseases such as diabetes, gastrointestinal conditions and cardiovascular problems.

“They’re carrying a big secret about their parents,” he pointed out. “So there’s the behavioral thing of keeping still, keeping quiet and behaving. I often jest — but a very serious jest — that I seldom see the child of an immigrant throwing a tantrum at Walmart. And it’s true, because they have to maintain a self-regulation or their parents will get into trouble. So what does that mean?

“It means they can be separated from their parents, and not know when, or if, they’ll ever see them again,” he said. “So for children, it’s really troubling, possibly leading to behavioral, mental and even cognitive problems where their thinking is disturbed. And it can also exacerbate other medical conditions like asthma.

“With the constant stress, your body is always on alert, and the hormones it secretes don’t stop. And there’s only so much, without rest, that the body can take.”

The clinical social worker and psychologist then brought up a couple of recent cases. A few weeks ago he met with a boy wearing a baseball cap, football jersey, jeans and sneakers, looking like the stereotypical American adolescent.

First they made small talk about his favorite food and drink. Eventually, the conversation turned to his detained undocumented father, and how he was probably going to be sent back home to Honduras. Realizing how his family was breaking apart, the boy suddenly got emotional and could barely contain himself, Zayas recalled.

In a case about a year ago, two brothers didn’t even know their dad wasn’t legal — so when they were pulled over on a street, they had no idea what was happening.

Their mother, a U.S. citizen, offered no explanation. The older brother happened to see a news spot about a father being deported and showing his kids crying. When he asked, “Could that happen to daddy?” his mother finally explained and acknowledged it could.

But the younger son still didn’t understand the situation and why everybody was so sad. It was only just before Zayas evaluated him that his mother tried to explain.

“When you see into these kids, the biggest dread is they’ll be losing their parents or that they’re going to go to a place that they don’t know with their parents,” Zayas said.

That’s the King Solomon choice that undocumented parents with U.S.-citizen children have to make. U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) doesn’t keep statistics about how many parents take their kids with them or leave them behind when deported.

“ ‘OK, if I take them with us, well, they’ll be with us and we can kiss them goodnight and make sure they say their prayers,’ ” the social scientist said in a different voice. “ ‘But we’re going back to a poor little hamlet in Mexico with nothing. So they won’t have the good health care and education, and language and culture they’ve become accustomed to.’ ”

After a moment, Zayas added, “That’s a hard decision that parents have to make.”

rn

rn

rn

Positive affirmations

Few Mexican immigrants can forget the words of then-candidate Donald Trump from his presidential announcement speech: “When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best. … They’re sending people that have lots of problems, and they’re bringing those problems with us. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. And I assume, some are good people.”

Cindy, the fourth-grade teacher, says she’s been trying hard to counter the almost daily stream of statements and actions from the White House targeting undocumented immigrants.

The young teacher agrees with behavioral clinicians and researchers like Luis Zayas. These specific condemnations coming from the president of the United States can severely damage the developing self-image of young elementary schoolchildren. Earlier this school year, a girl in her class asked, “Why does Trump hate Mexicans?”

“I’ve just seen them stressed out and they’re more anxious than usual,” she said. “And I ask them to pray for the person who you feel is causing you harm or anxiety or sadness. That’s all I can really do.”

There’s a dark blue “affirmation” section of a side wall with named pockets so students can write posted notes to one another. She picked out one that read, “You are nice and smart and cool.” And after lunch it’s usually “daily reflection” time, when students go over both good and bad thoughts that come to mind.

A “growth mind-set” poster is even taped to the wood door. The words inside one of the offshoot circles read, “Always believe in yourself, even when others don’t believe in you.”

Cindy said she’s just trying to create a safe and positive environment for her fourth-graders, whatever the legal status of their parents happens to be.

“I honestly think my own background is what’s helping us connect,” she pointed out. “I feel like I can really relate to all my students. I’m doing all the things that I wished somebody could have done for me in my situation and walked me through it. Like when I was dealing with having parents I might never see again or be taken to live in a place I really didn’t know.

“I just tell my kids ‘You’re not the only one.’ ”

• • •

rn

rn

rn

The battle ahead

Restricting immigration and stepping up deportations of undocumented immigrants have been two of President Donald Trump’s top priorities since becoming president. His administration has had some success accomplishing those goals, but legal and political battles remain.

Plans for Trump’s promised “border wall” have gone ahead, even though Congress has yet to approve most of the federal funding needed to build or replace hundreds of miles of border barrier between the U.S. and Mexico.

Immigration enforcement efforts have ramped up. Encouraged by the Trump administration, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) street-level officers and field directors have been given more latitude to choose which undocumented immigrants they can arrest and process for deportation.

A Feb. 2 Washington Post article referred to this as “taking the shackles off” of immigration officials who were ordered to focus on rounding up undocumented immigrants with criminal records during the Obama era.

That’s likely why arrests by ICE officers went up by 40 percent after Trump took office in January 2017, according to statistics from the Department of Homeland Security. The biggest increase in arrests has been of “noncriminal” immigrants, a group that previous administrations tended to avoid targeting.

For immigration advocates, the biggest hope for progress remains the status of so-called Dreamers, the name given to those brought to the U.S. as children by undocumented parents or family members. An Obama-era program known as DACA protected Dreamers from deportation and provided them permission to work.

Although Trump ended the DACA program on March 5, a federal judge in late April found the decision “arbitrary and capricious” because the Department of Homeland Security failed to “adequately explain its conclusion that the program was unlawful.”

Eventually, the program’s future may ultimately be decided by the Supreme Court.

Meanwhile, a compromise crafted by a group of lawmakers may offer President Trump a way out of this legal battle. The proposed bipartisan USA Act introduced in Congress earlier this year would boost border security and U.S. efforts to help Central American countries address the root causes of illegal immigration, as well as permanently protect Dreamers from deportation and provide them a path to citizenship.

The U.S. bishops, including Los Angeles Archbishop José H. Gomez, recently urged Congress to pass the bill as a replacement for DACA.

In January, Trump famously told a bipartisan group of lawmakers that he’d sign whatever immigration bill was sent to him by Congress. “I’ll take the heat” he pledged. “I don’t care.” Could this be his chance?

Interested in more? Subscribe to Angelus News to get daily articles sent to your inbox.