Cardinal Roger M. Mahony has been a bishop for 40 years and a cardinal for 25. With his 80th birthday a few months away, the cardinal sat down with The Tidings to share his thoughts on the many surprises in his ministry.

The cardinal was quick to quash questions about his career accomplishments. In his answers, he pointed constantly to God’s providence, not his own merit.

“One thing leads to another and you look back on it and you see God’s hand in all of this,” he said. “So I often think of the expression the saints often use: ‘God draws straight with crooked lines.’ It’s true. That’s the way the Lord works.”

The cardinal was raised in North Hollywood, where his father had a poultry processing plant. Some of their employees were Spanish-speaking, so he learned the language.

A ranch with acres of orange trees, orchards and corn was behind the plant. Latino immigrants took care of the ranch. He and his twin brother loved it.

“What they would do for lunch is pick corn right off the corn stalks and bring them over and barbeque them, add butter and salt, and they would share it with us. And let me tell you, we could hardly wait for summer,” he said.

By eighth grade, thanks in large part to the Blessed Virgin Mary sisters, it was pretty clear Cardinal Mahony had a vocation to the priesthood. He attended a high school that prepared young men for the seminary. At St. John’s Seminary, he first learned of the unjust treatment of farmworkers. Priests from the seminary would go and celebrate Mass for migrant workers.

“They had absolutely no rights,” he said. “At the end of the week they would get their paycheck, but they would get what we’d call today a print-out, and they would get charged for everything — rent of a cot, rent of a towel, rent of plate and utensils. They were deducting all this stuff.”

The cardinal never forgot.

He was ordained a priest for the Diocese of Fresno in 1962, in the middle of the Second Vatican Council. But his education wasn’t finished. He was asked to enter a graduate program in social work at the Catholic University of America.

“What? I was studying 20 years to become a priest and go to work in the parish with the people. The last thing I wanted to do was to go to school again,” the cardinal said.

“But God’s surprises are always things we don’t count on because we don’t understand the big picture. So I went back and got my masters in social work and came back and was put in charge of Catholic Charities,” he said.

A year later, Cesar Chavez began to organize the farmworkers in Delano. Fresno Bishop Hugh A. Donohoe asked then-Father Mahony to get involved.

“If I hadn’t of had those two years of education and experience, I would have been at a worse loss that I was,” Cardinal Mahony said. “How do you get the growers and workers together? What made it more difficult was that both the growers and the workers were Catholics. So they both said, ‘The Church has to be on our side.’”

The cardinal’s tact wasn’t to take sides, but instead he tried to moderate an agreement — fair wages and benefits for the farmworkers, and profits for the growers.

“Those were grueling years,” he said, noting the mixed results.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Cardinal Mahony was involved in farmworker negotiations and attended meetings of bishops in California and Arizona, though he also traveled to Texas and Florida.

Another surprise awaited the cardinal in 1975 — being named auxiliary bishop of Fresno, serving under Bishop Donohoe. “It was totally out of the blue,” the cardinal said.

Providentially, the cardinal was ordained a bishop on March 19 — the Feast of St. Joseph, his personal patron saint. He had been ordained a priest on May 1 — the Feast of St. Joseph the Worker.

A couple of months later he received a call from Governor Jerry Brown’s office.

“So I went up there and [Governor Brown] said, ‘Oh, I’m trying to get together the [California Agriculture Labor Relations Board] and I want you to serve as a member and be the first chairman.’ I said, ‘You gotta be kidding me. Well, I just became bishop a couple months ago. I don’t think the Holy See is going to let me do this.’

“Long story short, within a week, the Holy See said yes I could,” the cardinal said. “The Church has been advocating for so many years for the rights of farmworkers and here’s a chance to be a part of the solution, they said.”

The cardinal, who would eventually facilitate major change in labor rights, had been appointed to help Bishop Donohoe lead a diocese with a huge geographical region. But it turned out he wouldn’t be able to do that with his duties in Sacramento.

“That’s why I call this a journey of God’s surprises,” he said, “because every time I turn around, there’s something. ‘What? Where did that come from?’”

Five years later, God revealed yet another surprise.

“Never in my wildest dreams did I think I’d be the bishop of Stockton,” he said. “But it was a lovely life. The San Joaquin Valley and the Sacramento Valley are one huge area of agriculture — very similar.”

In April of 1980, the cardinal became the bishop of Stockton, one of the smallest dioceses in the United States. He loved it. A land that burgeoned during the gold rush, where little churches built by the miners still serve small towns.

He was in his cabin in the High Sierras when his vicar general told him that the apostolic nuncio — Archbishop Pio Laghi — was trying to get ahold of him.

“So I call him and he says, ‘Oh, well, the Holy Father is appointing you to another diocese,’ and he didn’t say where at first. Then he just started talking about it, you know, ‘there’s a number of issues, a lot of Spanish-speaking Catholics there, a lot of things that need to be taken care of…’

“He’s going on and on and on. And I’m saying, ‘Archbishop, I appreciate this, but where? What diocese is this?’ And he says, ‘Oh, I didn’t mention that, oh. It’s Los Angeles.’

“I said, ‘Los Angeles? You’ve gotta be kidding me!’ I said, ‘That’s the largest archdiocese in the United States. I’m in the smallest diocese in the United States. This has got to be a mistake. You can’t have me going to Los Angeles.’

“‘No, yeah, that’s what Pope John Paul II has decided. That’s where you’re going.’ I thought, ‘Oh, I can’t believe it.’”

The cardinal called it fortuitous to receive the news while he was at the cabin. He was doing little repairs and no one was visiting.

“It gave me a lot of wonderful time to take long walks in the pines and just really pray and reflect and just say, ‘Lord, you’ve gotta be kidding me,’” the cardinal said. “How could there be any more surprises than this.”

In 1986, the cardinal divided the archdiocese into five pastoral regions — Our Lady of the Angels, San Fernando, San Gabriel, San Pedro and Santa Barbara. In 1991, St. John Paul II elevated him to a cardinal, the third in the history of the archdiocese.

In 1995, the cardinal announced plans to build the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels to replace St. Vibiana’s, which had been badly damaged by the 1994 Northridge Earthquake.

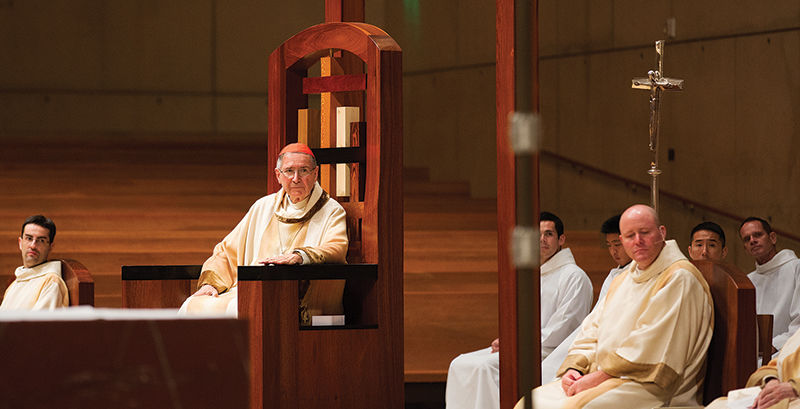

On All Saints Day this year, the cardinal celebrated Mass at the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels to commemorate his years as a priest, as a bishop and as a cardinal. Describing himself as an “unprofitable servant,” he confessed to asking himself “what if” questions.

“What if I had dared taking more risks in order to be a better instrument of God’s peace and justice?” he said of his work on behalf of farmworkers.

He spoke about the “scourge of the clergy sexual misconduct of minors,” calling it an “unthinkable evil” that rose from a “murky darkness.”

“I was stunned to learn that any priest could possibly harm children and youth in this dreadful manner,” he said.

While he recognized failings, he also held up the example of the saints depicted in the cathedral’s tapestries — 125 men and women “who lived out their discipleship with Jesus in heroic fashion.”

The cardinal took part in the 2005 conclave that elected Pope Benedict XVI and the 2013 conclave that elected Pope Francis. Here, too, he found the unexpected.

“What I wasn’t really expecting was the real powerful presence of the Holy Spirit,” he said of the conclave that elected Pope Benedict. “I had no idea how strong that was going to be. It was palpable.”

The media, the cardinal said, just doesn’t know how to cover something like a papal conclave.

“Their only frame of reference is political and legislative elections. They can’t imagine that you don’t have all that nonsense going on because they don’t have the Holy Spirit involved,” he said.

The surprise of the second conclave, which the cardinal said had the same, palpable presence of the Holy Spirit, was the move to the southern hemisphere and Latin America.

“And a Jesuit! But it was obvious the Holy Spirit was leading us,” he said.

Reflecting on his time in the archdiocese, the cardinal said it has been blessed with “such marvelous priests,” and praised his predecessors. He said the Archdiocese of Los Angeles has a rich history, one that Catholics can learn about through the many books of Msgr. Francis J. Weber, the archdiocesan archivist emeritus.

Msgr. Weber’s writings, he said, reveal “a fascinating history, and you look back at God’s plan and how things unfold. You know, all the first bishops were Hispanic. It wasn’t until Bishop [Thomas J.] Conaty in 1903 that we switched primarily to Irish bishops.”

The cardinal, from his time in Fresno, has believed in leadership by minorities. Before becoming bishop of Fresno, Bishop Armando X. Ochoa was named auxiliary bishop in Los Angeles in 1987. In 2003, Bishop Oscar A. Solis was one of the first three Asian bishops in the United States — all of which were named to California dioceses.

“I was very anxious that we go back to a Hispanic archbishop,” he said of retiring as archbishop of Los Angeles. “So I was delighted when Archbishop [José H.] Gomez was appointed as co-adjutor in 2010.”

Nowadays, the cardinal celebrates Mass at a different church every Sunday. While the pastors want him to join them for a cup of coffee in the rectory, the cardinal prefers to be with the people.

“I say, ‘No, no.’ They all have groups of people selling doughnuts, and the Mexican and Salvadoran places have people selling coffee and pastries, ‘No! I’m not going to the rectory,’” the cardinal said.

“I’m going to have a cup of coffee with these folks,” he said. “I always go into the kitchen to talk to the cocineras. I always go out of my way to talk to the groundskeepers.”

The cardinal is still making connections like he did as a kid on his father’s poultry farm in North Hollywood. And he’s still enjoying Hispanic cuisine.