A tradition started last year, the second annual Healing Mass for victims of crime and violence at St. Andrew Church, welcomed not only parishioners but members of other faith communities to come together for prayers and blessings.

The emotionally-charged, bilingual Mass began with organizers passing out healing cards for worshippers to write down names of those who have been affected by crime and violence as intentions.

Father Paul Sustayta, pastor and presider, set the reflective tone for the Eucharistic celebration which combined personal testimonies, blessings, songs and prayers. “We are here to celebrate God’s gift of healing and forgiveness in our lives,” he said, welcoming members from other faith communities.

Organized by the parish Peace and Social Justice Committee, the Healing Mass was held in October, Respect Life Month, because “it’s important to remember that a lot of people grieve in silence because of violence or crime,” said committee member Noel Toro. “Here is a way we can all come together to help each other better understand that pain.”

In his homily, Father Sustayta explained the often long-process of healing from traumatic events. He described how a 15-year-old football player suffered a bad injury on the playing field which left him a quadriplegic 36 years ago. The ICU nurse who cared for him after he was brought to the hospital was upset, thinking it was unfair that such a devastating moment changed this boy’s life forever.

The boy, however, told her, “Whatever path God has chosen for me, that’s the path I’m willing to take.” The boy went on to graduate from high school and college and was recently ordained a minister this year --- all being in a wheelchair and on a ventilator.

“This is a story of justice, acceptance and forgiveness,” says Father Sustayta. “This is the transcendent message of healing that comes neither from revenge nor hatred.”

After the homily, three people shared personal testimonies. One woman described what it is like to love a person who has been incarcerated for 26 years.

“It has been a long journey for me,” she said explaining that two words rejuvenate her in her dark moments: healing and forgiveness. “I often think of the victims of this crime --- the other family but this one, too. [My husband] has missed the beautiful and powerful experience of seeing his son grow up. Please keep the victims and the incarcerated in your prayers.”

Another woman came forward to share her story of losing two brothers who were murdered. “I often go back to the day when he was killed; he had just celebrated his 22nd birthday,” she said. Because of this traumatic experience, she found a career in helping people who have been victims, “walking with them as they heal. I have seen transformations in people. I continue to work every day on my own healing, as well.”

Finally, a member of Homeboy Industries told his own story about growing up not just with the gangs of Boyle Heights, but living in a household where his father, unable to find a job after moving his family here from Mexico, turned to selling and doing drugs. “My innocence was robbed,” he recalled. “[My father] brutally beat my mother and I looked around and all I saw was drugs and violence.”

After his father was sentenced to prison, the young man described his anger and confusion which led him to join the local gangs. It was after his second failed suicide attempt that the man realized that he was “blessed with the gift of life” and needed to make amends to himself, his family and his community.

Using his artistic talents, he created a mural in Boyle Heights that he unveiled on Mother’s Day to a large crowd, many of whom were mothers. “I asked each of them, pointed to each one, asking for their forgiveness for what I have done,” he said. “But they came to me and said, ’No, we weren’t there for you. Can you forgive us?’ I want everyone to know that yes, people can change.”

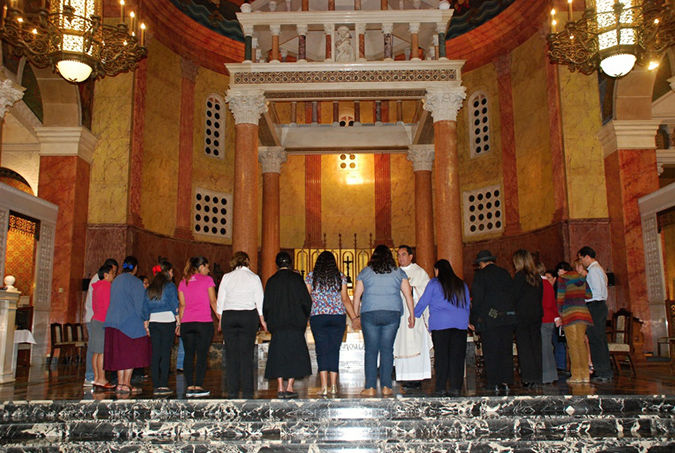

At the recitation of the Our Father, Father Sustayta called forth all victims and loved ones of victims of a violent crime to join with each other at the altar. Into a microphone, they said the names of their loved one, whether it was a victim or someone incarcerated. After the prayer, individuals gave each other hugs at the Sign of Peace.

Fittingly, the Prayer of St. Francis was sung after Communion, encouraging worshippers to realize the power of meeting hatred with love.