When Norma Cumpian arrived at the California Institution for Women (CIW) in Corona in the mid-’90s, all the inmates thought she was a snitch. She had to be “planted,” they thought. No one ever got transferred there from the Central California Women’s Facility (CCWF) in Chowchilla, doing life.

But the young woman did, and the move would radically change her life. Because now her toddler son, being cared for by her parents in Orange County, could see her on a regular basis — and that made all the difference in a 16-year struggle to not become hardened by the Golden State’s penal system.

“I was told, ‘CIW is closed to people with your life sentence,’” Cumpian recalls today. “And I don’t know what told me to do it, but I said, ‘Look, I’m not trying to act like I’m better than anybody else here or that I want something special. But this is the only child I’ll ever have. And I just want to be able to be a part of his life. I’m not like a screw-up. This was just a one-time thing.’

“Then she looked at me, and she opened up the folder, and she wrote something and slammed it. And she said, ‘That’s so you can 602-it,’ which is an appeal. I didn’t know what that meant at the time, but something told me to shut up and wait. I didn’t think anything happened. But later I got a note shoved under my door that said, ‘CIW endorsed.’ So when I got to CIW, all the women there thought I was a snitch.”

But then an inmate from a Los Angeles County jail, where Cumpian was locked up for two years, recognized her: “That’s Norma. That’s the little pregnant girl. She’s not a snitch. She’s cool.”

Cumpain’s crime was domestic violence, with another family also tragically involved. The sentence was seven years to life. Then it was up to Chowchilla for six months before the unexpected transfer closer to home. Still, being an inmate took its toll.

“Living as a prisoner, you know, you’re so powerless,” the 44-year-old woman explains. “And you have nothing. People have basically, like, thrown you away. And you feel like you’ve been thrown away. You’re embarrassed about what you’ve done, and you are humiliated.”

She grew up in Orange County, and for a “little while,” went to parochial school. Her working class family was very involved in their parish. Her devout Catholic mother had a statue of the Virgin Mary in their back yard on a mound, surrounded by sea shells from a favorite beach in Mexico. Written on each shell was a different prayer.

“I was ‘busted’ for stepping on the mound to see over at our neighbors,” she says, laughing at the memory.

Culture clash

But Cumpian’s long stretch at CIW was never anything to smile about. At the beginning of doing hard time there, the young woman thought she would never get out of state prison. Her life was over. Visits from her son and parents, however, gradually gave her hope along with steadfast courage to change during her 16-year lockup.

“When you’re in a situation like that, incarcerated within the prison culture, it’s easier to do the wrong thing,” she points out. “So I would go out in the yard and be in that culture, but then I had an escape. I would see my son at visiting. And here’s this innocent child who almost, like, had a disability being born into this situation. And it’s not his fault.

“At first, I felt like there’s nothing I can do — this is just horrible. But then I got a job in the mental health department and was exposed to a lot of people who were really good role models. I also listened to a lot of women at CIW who were older lifers, and they said, ‘Norma, you can be a good person in here.’ I was like, ‘What?’ And they were like, ‘You can do it. You need to start educating yourself.’”

Which is what Cumpian did.

Over the years she read all the books in the prison library. Her treat on Saturday was to take out a “junk food” title by Stephen King or another pop author along with some deeper tome on history or philosophy or religion. Her brother would bring her biographies of people like Nelson Mandela and Malcom X, who had endured horrendous behind-bars experiences and actually grew from them.

She also enrolled in trade schools at CIW and taught herself how to public speak properly. There was also the dog program, where she lived, 24/7, with different canines for years, training them to do tasks for people with disabilities.

“So then I kind of started seeing it in a different way: ‘If I can make myself this great role model, even though I’m in prison, that’s going to be my son’s reality. So why don’t I do that?’” she recalls asking herself. “And my mother, who is very devout, she gave me one bit of advice that stuck with me for my whole time inside. She said to me, ‘Norma, make your decisions and conduct yourself like your son is standing next to you.’

“He was so bright, he still is. And he would call me on stuff, on my principles — only five, six years old, but his reality was coming into prison to visit his mom, and he didn’t have a dad. So his mentality was a lot different than other kids. They were playing ‘ring-around-the-rosy’ and he’s like, ‘How do you feel about the death penalty?’”

But it wasn’t her son’s intelligence that inspired her metamorphosis.

“What really made the difference was unconditional love — from my son and parents, older inmates and the nuns like Sister Suzanne [Jabro] and Sister Mary Sean [Hodges] who visited us,” observes Cumpain. “I told myself I knew I was going to get out, and I wouldn’t allow myself to become an ugly person. I wanted to make myself a good person so I could give my son as good as I could possibly give him.”

GOTB pizza party

Norma Cumpian knows firsthand what a visit from a child means to a locked-up parent — as well as to that son or daughter. Since the single mother got out of prison in December of 2010, she’s worked for “Get On The Bus” (GOTB), a nonprofit with the mission of uniting children with their incarcerated mothers and fathers. Today, she’s a regional coordinator of the state-wide program started by Sister Suzanne Jabro in 1999.

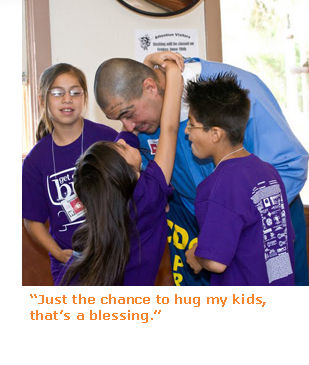

GOTB handles the detailed paperwork needed for clearance into prison. It also provides transportation on chartered buses to and from prisons in California, plus chaperones for children who don’t have any adult to accompany them. And it enlivens drab visiting rooms with a pizza party, featuring games and photo opportunities, arts and crafts, and other child-centered activities.

“After all these years, it is amazing how many of the children we are now accompanying who are still meeting their father or mother for the first time,” says Sister Jabro, executive director. “And how many of them, even if they’re older, are looking at this dad or mom to see themselves reflected in them. They have the same color hair or the same color eyes. And they’re trying to mirror themselves.

“So it’s an identity issue,” notes the Sister of St. Joseph of Cardonelet. “Whether they ever lived with their parents or not is another story. The identity issue is so critical to their life as a person. But it works both ways — the need of the child to see their parent, and the need of the parent to see their child. The parent needs to know they have another life and remember that, because the prison subculture just eats you alive.”

Meanwhile, Cumpian’s nearly 21-year-old son is a decorated sergeant in the U.S. Army, with a Purple Heart from being wounded in Afghanistan.

Volunteers can start a GOTB team in their community, parish or faith group, or organize a fund drive in a school, church, temple or mosque. Donors are needed as bus benefactors, event sponsors family supporters or be “Child’s Angels.”Information: (818) 980-7714 or [email protected] and www.getonthebus.us.