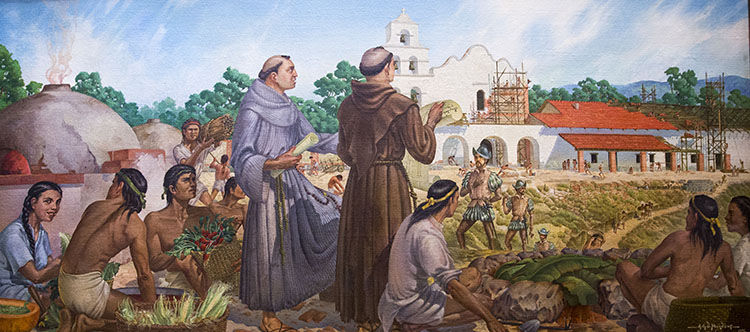

Franciscan Friar Junípero Serra, joined by a Native American companion, walked from San Diego to Mexico City for an unannounced visit with Viceroy Antonio Maria Bucareli y Urs√∫a in 1773.

Another friar had told him of a soldier who had raped two native women. Father Serra, nearly 60, was so outraged he decided he was going to do something about it, according to archeologist Ruben Mendoza.

Upon Father Serra’s insistence, the viceroy had the soldier’s commander removed for tolerating such behavior.

During the same visit, Father Serra presented the viceroy with “La Reprecentación,” or the “Representation,” a 33-point document that put forth the case for separating the work of the missions, the colonists and the military.

The document called for “justice for indigenous peoples living in the missions,” according to Archbishop José H. Gomez. Father Serra called for strict moral standards for the soldiers and for the removal of corrupt commanders.

Pope Francis canonized Junípero Serra Sept. 23 at the Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, D.C. The pope recognized Father Serra’s defense of rights of the indigenous as well as his missionary zeal.

“He was one of the founding fathers of the United States, a saintly example of the Church’s universality and special patron of the Hispanic people of the country,” the pope said during a May 2 homily at the Vatican. “In this way may all Americans rediscover their own dignity, and unite themselves ever more closely to Christ and his Church.”

Saints are men and women who live exemplary lives in their relationship to God and others, according to Archbishop Gomez. Saints show us how to live good Christian lives.

Father Serra dedicated time to pray and speak and hear God, he said.

“It’s something very important for all of us, in the society in which we live, we’re so busy that it can be a challenge to make time for God,” the archbishop said.

As a missionary, Father Serra left behind a promising academic career to share the Gospel with the people of North America. He was constantly dogged by ailments and faced resistance to his view of the role of the mission.

“His simple desire was to communicate the beauty and the teachings of the life of Jesus with others,” the archbishop said. Father Serra established the first nine of 21 missions in California, living out his motto: “Always forward, never back.”

Earlier this year, Archbishop Oscar Romero was beatified in San Salvador. Archbishop Gomez said, while the two men need to be appreciated in their historical context, both Blessed Oscar Romero and St. Junípero Serra reflect the pope’s vision for the Church.

“In the case of Archbishop Romero, he lived with the constant threat of violence from the Salvadoran government. In Junípero Serra’s case, amid the violence that was committed against the native peoples,” he said. “The two were constantly on the side of love, of justice and of service, respecting the dignity of the human person.”

When Father Serra first arrived, a spider bit and infected his leg on his way from Veracruz to Mexico City. The indigenous cared for him, but his concern was not for his own health, but theirs, the archbishop said.

Pope Francis is calling the Church to be a field hospital and for pastors to smell like their sheep. Father Serra did that, according to the archbishop.

“His concern was not for himself, but for his sheep,” he said. “And they got along and treated each other well — he learned their language and their culture.”

nCultural and ethnic genocide

Many Native American groups have met the canonization of Father Serra with outrage. In a recent release, one group names Father Serra as “the principal perpetrator for the oppression against our ancestors.” He’s accused of “capturing, enslaving, whipping and torturing Indians.”

The controversy over Father Serra’s legacy is not new, according to Ruben Mendoza, a professor at California State University Monterey Bay who is of both Yaqui and Mexican American heritage.

In 1934, the Congregation for the Causes of Saints began the process of Serra’s canonization. In the 1940s, Father Maynard J. Geiger gathered nearly 7,500 pages written by Father Serra while Father Eric O’Brien interviewed more than 2,000 descendants of California settlers, Indians and Spanish who knew Father Serra in the Diocese of Monterrey-Fresno. In 1950, the diocese handed over their research to the Vatican, at which time Father Serra was recognized as “Servant of God.”

St. John Paul Il recognized Father Serra as “Venerable” in 1985 before he beatified the priest in 1988. At that point, Father Serra’s intercession was credited with the miraculous healing of a nun with lupus.

In January, Pope Francis announced he would canonize Father Serra as a saint during his visit to the United States.

When the Spanish arrived, there were an estimated 330,000 Native Americans in California, though estimates vary.

“When the mission period ended 62 years later, 100,000 disappeared,” said Auxiliary Bishop Edward Clark, the California Catholic Conference’s liaison with Native American communities. “After that, it got worse.”

The Native American population in California dropped to 20,000 by 1900. Historians typically break this time into three periods: The Missionary Period (1769-1821), the Mexican Period (1822-1848) and the American Period (beginning in 1848).

Under Spanish rule, the intention was for Native Americans to become citizens of Spain. Still, during the missionary period, many died from diseases, including smallpox, according to Bishop Clark.

“They died from hunger because, with the best of intentions, Europeans came to establish European-style agriculture, which destroyed the natives’ natural food gathering, and they starved,” he said.

“Their culture was displaced and that killed them,” he said, explaining that many Native Americans fled colonization. “Some of them died, later, but even during the mission period, soldiers killed them. They abused them.”

The Mexican government secularized the missions in 1834. The government gave land grants, making the missions ranchos.

“These grant owners didn’t want natives on their property, so they ran them off or killed them,” Bishop Clark said. The Franciscans had intended for the land to be left for the Native Americans.

During the American period, Native Americans were bought and sold as slaves.

“You could buy a slave on Olvera Street, you could buy an Indian,” Bishop Clark said. “There was a real genocide of the Native Americans after the missionary period. The first governor of California said that California will never be a true state until we get rid of the Indians. He actually called for them to be eliminated.”

During the California Gold Rush, it was not illegal to kill a Native American.

Gregory Orfalea, author of “Journey to the Sun: Junípero Serra’s Dream and the Founding of California” and writer-in-residence at Westmont College in Santa Barbara, said Father Serra cannot be accused of genocide.

“What the Americans did in all but extirpating Indians from the continent was genocide. What the Spanish did, at least in California, was not,” he wrote in an Aug. 31 article in Commonweal magazine. “The missions were designed to attract Indians, not destroy them.”

Father Serra did not believe in forcing Native Americans to be baptized. They had to choose it for themselves. Yet once they entered the missions, Native Americans were not allowed to leave without permission. If they did, they were punished.

“He was an individual, in this case, that was a person of his time. He didn’t go against these notions of the period,” Mendoza said. “But what has to be understood is that corporal punishment at this time was not restricted to native peoples.”

Commanders in California ordered the beatings of soldiers disobeying or abandoning their posts, he said.

“Serra and the Franciscans were concerned by the fact that the Spanish conquistadors dominated the Indians in an oppressive manner,” according to Robert Senkewicz, professor of history at Santa Clara University.

“They were worried that the Spanish landowners, the miners and the soldiers would gather them up to take them to their deaths,” he said. “That is why they founded the missions as a safe place to convert and protect the Indians.”

Father Serra has also been accused of “cultural genocide.”

“The missionaries came very definitely to change the culture of the Indians. They wanted them to be citizens of Spain, which meant they had to do away with their culture,” Bishop Clark said.

“In some places, they were forbidden to sing their songs, do their dancing, carry on their traditions in some of their missions,” he added. “But the overall goal was to get rid of the Native American culture and make them citizens of Spain. True citizens, so that meant true European, and Serra came with that in mind. That was his commission.”

Still, Msgr. Francis Weber, archivist emeritus of the Archdiocese of Los Angeles and the author of several books on Junípero Serra and the California missions, doesn’t think the saint is guilty of “cultural genocide.”

“Such a charge irresponsibly conflates Serra’s missionary work with the misdeeds of Spanish colonialism, and thus may be seen as a contemporary form of the Black Legend,” he wrote in an April 1 article in Columbia Magazine.

“Some historical perspective is in order. Given the explorative patterns of the time, the colonization of California in the 1760s was inevitable. The missionaries were not unmindful of history; they voluntarily became part of the process in order to Christianize and to cushion what they knew would be a major cultural shock.”

Msgr. Weber further noted that Father Serra sought to separate military involvement from his missionary work.

Msgr. Weber noted that, before the beatification of Father Serra in 1988, St. John Paul II said the Church is called to learn from the mistakes of the past during a 1987 visit with Native Americans in Phoenix.

“Unfortunately not all the members of the Church lived up to their Christian responsibilities,” he said. During a recent visit to Bolivia, Pope Francis also apologized for the “many grave sins were committed against the native peoples of America in the name of God.”

“I would also say, and here I wish to be quite clear, as was St. John Paul II: I humbly ask forgiveness, not only for the offenses of the Church herself, but also for crimes committed against the native peoples during the so-called conquest of America,” he said.

“Let us say no to forms of colonialism old and new,” Pope Francis said. “Let us say yes to the encounter between peoples and cultures. Blessed are the peacemakers.”

Earlier this month, the California bishops announced a program to review and revise the cultural content and displays at the California missions under Church authority. The program will also review the third and fourth grade curriculum in Catholic schools to better reflect modern understandings of the mission era and the relationship between Spanish civil authority, the Catholic missions and local Indian tribes.

“The mission era gave rise to modern California, but it also gave rise to controversy and to heartache when seen through the eyes of the first Californians,” said Sacramento Bishop Jaime Soto, president of the California Catholic Conference. “For many years, the Indian experience has been ignored or denied, replaced by an incomplete version of history focused more on European colonists than on the original Californians.”

nSan Diego revolt

Father Serra found much turmoil when he returned from his meeting with the viceroy in Mexico City. The 1775 San Diego Indian revolt is a sign of the challenges he faced at the time. During the uprising, the San Diego mission was destroyed.

Father Serra’s friend, Father Luis Jayme, was shot with 18 arrows and beaten to death during the revolt. When soldiers arrested those responsible, Father Serra asked that the men not be harmed.

“Serra’s response was that the blood of a Christian martyr has now landed in California, the time for the evangelization is now,” Mendoza said.

“Serra came to California, he gave his life, he was the great evangelist,” he added, noting that the pope is well aware of the controversy surrounding Father Serra. “Pope Francis was willing to take on the worst of this to recognize a man who truly was devoted to the community he served, the California Indians.”

Father Serra died Aug. 29, 1784, after a confirmation tour at the San Carlos Mission. His friend, Francisco Palóu, laid a large wood cross on his chest.

“More than 300 Native Americans came in and wept and prayed with Serra’s body,” Mendoza said. “They also began to remove fragments of his body and take locks of his hair.”

Father Palóu told them they couldn’t do this because he was not a saint and these were not relics.

“But the Indians begged to differ, ‘He was a blessed and saintly father,’” Mendoza recounted. “His colleagues, his compatriots and the Indians believed that he would be made a saint. But now, 240 years ago, we Americans are conflicted.”