Christianity — unlike other world religions — has never mandated pilgrimage.

But it didn’t have to. Christians just did it. Spontaneously. In impressive numbers. And often at great risk.

The Law of Moses required Israelite males to make three trips to Jerusalem every year, for Passover, Pentecost, and Sukkot (see Exodus 23:14–17; 34:18–23; Deuteronomy 16:16). In the early first century, the population of the Holy City doubled during these holidays as Jews arrived from all nations of the known world (see Acts 2:1, 9–11).

Pilgrimage is the fifth pillar of Islam. Muslims are duty-bound to make the Hajj, the pilgrimage to Mecca, at least once in their lifetime — and some 2.5 million people complete the journey every year.

For ancient Jews and modern Muslims, pilgrimage has occupied a place that’s comparable to the place of the sacraments in Catholic tradition. The Church, however, has never claimed such a place for pilgrimage. The New Testament doesn’t require it. Canon law has never mandated it. No catechism has ever presented it dogmatically.

Yet Christians have always done it. That’s clear from the documents of the early Church. It’s evident also in the archeological remains from that period.

A pilgrimage is a journey undertaken for a religious purpose.

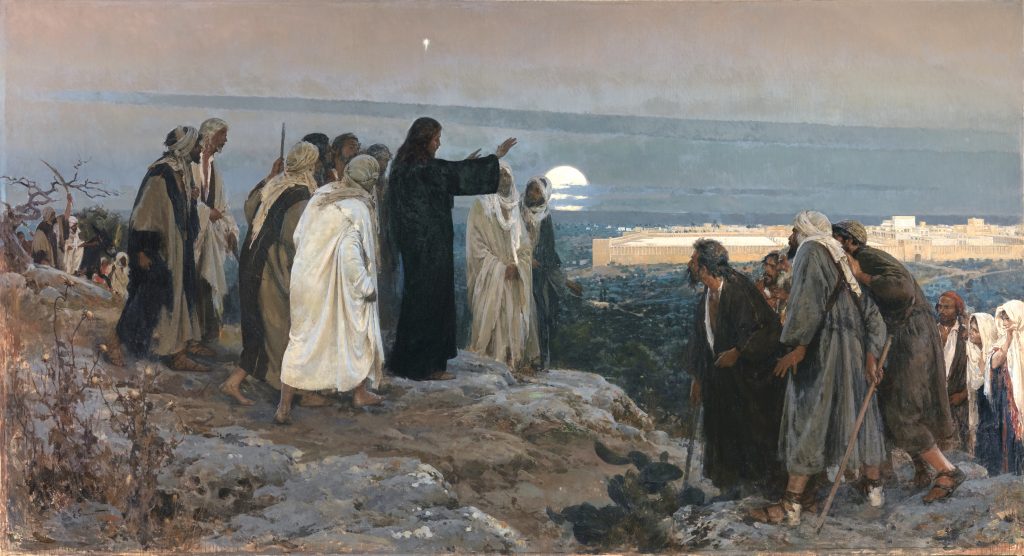

From at least his adolescence, Jesus fulfilled the command to celebrate the festivals in Jerusalem. It was his family’s custom (Luke 2:42), and the trip from Nazareth — on foot, on crowded roads — probably took between four and six days each way.

In adulthood Jesus continued the practice, not out of a sense of obligation, but rather out of love. It was his earnest desire (Luke 22:15). He set out for Jerusalem with determination (Luke 9:51). The pilgrimages were so important to Jesus that St. John uses them as the dominant structural element in the narrative of his Gospel.

The apostle St. Paul, even after his conversion to the Way of Jesus Christ, continued to make pilgrimage to Jerusalem for Pentecost (Acts 20:16).

And others followed his example. St. Melito of Sardis, in the mid-100s, made his way to the Holy Land in order to enrich his understanding of the Scriptures. A few decades later, the

Egyptian scholar Origen recounted his own sojourn in Palestine as a pilgrimage and availed himself of opportunities to visit the sacred sites.

The pagan Romans even took measures to discourage Christian pilgrimage. The pagan emperor Hadrian ordered that the cave of Jesus’ Nativity be buried and a grove planted over it, dedicated to the god Adonis. Every deterrent was in place; but believers visited anyway.

As the Church spread outward from Jerusalem, Christians made their way to other pilgrim destinations. There was Rome. St. Paul himself was led inexorably toward the empire’s capital (Acts 19:21, 23:11; Romans 15:30–32). St. Peter was, too. Both men sanctified the ground there by their martyrdom — and so drew many more pilgrims in their wake.

In the next generation after the apostles, in A.D. 107, St. Ignatius of Antioch felt himself to be propelled toward Rome, to die there as a martyr, but also to pay his respects to the place that was already regarded as the religious capital of Christianity — the Church that “presides in the place of the region of the Romans, worthy of God, worthy of honor, worthy of the highest happiness, worthy of praise, worthy of obtaining her every desire, worthy of being deemed holy, and which presides over love.”

In spite of persecution, Christians streamed to Rome and left their marks in graffiti at the burial places of St. Peter and St. Paul — and then at the sites associated with other saints.

Paul and Peter, pray for Victor! …

Martyrs and saints, keep Maria in mind …

O Hippolytus, remember Peter, a sinner …

Master Crescentio, heal my eyes for me! …

O St. Sixtus, remember Aurelius Repentinus in your prayers! …

O holy souls, remember Marcianus, Successus, Severus, and all our brethren!

In the fourth century, St. Jerome traveled from Croatia to Rome to pursue his studies; but he spent his Sundays wandering with a torch through the dark tunnels of the catacombs. There he prayed in a weekly pilgrimage.

Later in life, St. Jerome would go to Jerusalem, along with an entourage from Rome. They would become history’s most ardent promoters of religious tourism to the Holy Land. He describes the effect such an excursion had on his friend, St. Paula of Rome:

“She … started to go round visiting all the places with such burning enthusiasm that there was no taking her away from one unless she was hurrying on to another. She fell down and worshipped before the Cross as if she could see the Lord hanging on it. On entering the Tomb of the Resurrection she kissed the stone which the angel removed from the sepulcher door; then like a thirsty man who has waited long, and at last comes to water, she faithfully kissed the very shelf on which the Lord’s body had lain. Her tears … they were known to all Jerusalem — or rather to the Lord himself to whom she was praying.

Shortly after the Emperor Constantine legalized Christianity in A.D. 313, his mother, St. Helena, went abroad to see the holy places described in the Scriptures. In Jerusalem and Bethlehem she commissioned the construction of great basilicas in honor of the Savior. Christians from everywhere would throng these places, and they continue to do so today.

Believers also made pilgrimage to living saints and sages. St. Anthony of Egypt strove to live in the desert in poverty and solitude, but he was visited daily by the devout, the inquisitive, and the curious, who sought his advice or just his blessing. So diverse were the pilgrims — coming from every direction — that St. Anthony had to keep translators at hand, drawn from the monasteries nearby.

Why did the early Christians go on pilgrimage? They did it because Jesus did, and they wanted to follow his example. They did it because St. Paul had done it — the same St. Paul who said, “Be imitators of me, as I am of Christ” (1 Corinthians 11:1).

And so, down to our own day, Christians continue the pilgrim way.