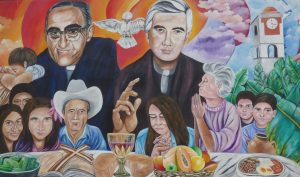

Last week, I watched the livestream of the beatification ceremony of four new martyrs of the Catholic Church from El Salvador: Father Rutilio Grande, SJ, Manuel Solorzano, Nelson Rutilio Lemus and Fray Cosme Spessoto, OFM. As a priest who spent 20 years as a missionary in their country after their deaths, it was an experience about events that happened far away and long ago that still seemed so near to me that it had me holding my breath at times.

A few hours later, I came across a quote from Father Paul V. Mankowski, SJ, some of whose essays have been collected in a book called “Jesuit at Large” (Ignatius Press, $15.26). In an essay on the Immaculate Conception, Father Mankowski wrote:

“If you think about the two or three saints to whom you yourself have the deepest devotion, is it not the case that part of what attracts and fascinates you about these saints is that you can recognize a certain kinship in the kind of fragility they possess, a fragility against which their heroism blazes with particular glory in your eyes, in your heart? Isn’t it the case that, since you can see God’s work in their weakness, you can come to accept the possibility of God’s working in your weakness, too?”

The thought reminded me of a saying common in Alcoholics Anonymous: “Your strengths are your weaknesses and your weaknesses are your strengths.” The fragility of a saint can be like stained glass that allows us to see the many colors in sunlight in a pattern of grace. In other words: God’s glory is more colorful when seen in contrast with human weakness. In the words of St. Paul, “It is when I am weak that I am strong.” (2 Corinthians 12:9–10)

Yet this idea did not come through so clearly at the beatification. I was thinking especially of the most well known of the four martyrs, Father Rutilio Grande. The ceremony highlighted his commitment to the evangelization of the rural poor, and to his pursuit of justice for them. Much was also said about the 12-year-long bloody repression before and during El Salvador’s civil war. And the theme of “reivindicación,” or justice for those ignored in history, was also prominent.

What was not emphasized was how the four died in the crosscurrents of a violent conflict that reached far beyond the borders of El Salvador. St. Oscar Romero’s successor as archbishop of San Salvador, Arturo Rivera y Damas, used to say that El Salvador was a battlefield in the Cold War between the U.S. and the Soviet Union, with the combatants as pawns of ideologies and concerns not always in their own interest.

The archbishop had another metaphor for the war and what it called the Church to do. When a house was on fire, he would explain, the first thing to do was get its inhabitants out of harm’s way. Then, of course, you had to see the cause of the fire.

The four new blesseds were all burned alive in the fire of social conflict in El Salvador. Fray Cosme was a religious, almost perfectly apolitical. The two laymen who accompanied Padre Rutilio were hardly figures of revolution.

It was Father Grande, on the other hand, who was considered a revolutionary. A pastor in a poor region of rural El Salvador that was boiling over with agitation, he had a reputation as a fiery orator and an opponent of the government. His rhetoric was sometimes very sharp, as when he characterized the government as “established disorder,” which served only the minority of rich “Cains” oppressing their brothers “Abel.”

I remember Archbishop Rivera saying to me that Father Grande was not served well by many who claimed to idolize him and made him a political icon. He was not “political” but “pastoral,” even though some of those who worked with him were ideologues. A pamphlet written by one of his colleagues changed St. Paul’s confession from, “Woe is me if I do not evangelize” (I Corinthians 9:16) to “Woe is me if I do not conscienticize and politicize.”

Msgr. Fabian Amaya, a great figure in the Church in El Salvador, famous for his sympathy with the opposition, once told a group of us American missionaries that Blessed Rutilio was radically a pastor more than a radical pastor. He said that shortly before his death, Father Grande had “purged” the pastoral leaders of the Christian communities who were heads of the cells of the generally left-wing “organizations.”

He had no trouble with commitment to the organizations that eventually incorporated in the armed revolt against the government, said Msgr. Amaya, but, as pastor, he emphasized that the Church could not be completely identified with any political movements.

As far as weaknesses and difficulties go, Father Grande had a few: He came from a broken home, had severe emotional crises (including, mysteriously, one before his ordination), and was often very uncomfortable as pastor amid social conflict.

He was a man of many contradictions: A lion in the pulpit, but also a priest in need of psychiatric help who asked his superiors to be relieved of his duties without success. He was a man of the people, but one who had the support of ecclesiastical authorities. He did not hesitate to criticize the powers that be on the national stage: In fact, he famously did so at a Mass for the feast of the Divine Savior, where he preached in the presence of the country’s president, as well as members of the country’s political and religious hierarchy. He sent two letters to the president explaining his pastoral work and sympathies as consistent with the Gospel and the country’s constitution.

Like Manuel Solorzano, the old man who was his sacristan, and Nelson Lemus, the young man who helped him in what he could in the parish, Father Grande met death in a place he should have been safe: on his way to a happy event, a novena Mass in his hometown honoring its patron, St. Joseph. A local man who had known Blessed Rutilio and his family all his life was the Judas who signaled the assassins to shoot at Father Grande’s car. The burning house that was El Salvador had three more victims.

I wonder what they would have thought of the pageant of their beatification, attended by the president of El Salvador and so many establishment figures. Did they watch from heaven and pray for their country still so badly divided, still struggling with the faith? I know I thought of George Bernard Shaw’s Joan of Arc with its conclusion: “O God that madest this beautiful earth, when will it be ready to receive thy saints?”