His pontificate began with the words “Be not afraid.”

The day of his solemn inauguration, Oct. 22, 1978, Pope John Paul II looked out upon the throng in St. Peter’s Square, and he preached a rousing, poetic homily. At its climax he issued a number of challenges, each punctuated with those words, “Be not afraid.”

It resonated, and it became his catchphrase, his rallying cry. He returned to it repeatedly in his preaching and writing. When he visited the United States in 1987, he told the young people of Los Angeles gathered in the Universal Amphitheater, “Dear young people of America, listen to his voice. Do not be afraid. Open up your hearts to Christ.”

The words assumed a life of their own. This was not Pope John Paul’s original intention, and it took him by surprise. In his 1994 book-length interview with Vittorio Messori, “Crossing the Threshold of Hope,” he said, “I could not fully know how far they would take me and the entire Church. Their meaning came more from the Holy Spirit.”

But what exactly was their meaning?

They did not mean that Pope John Paul was fearless, or that he expected anyone else to be. George Weigel observed in his second biography of the pontiff, “The End and the Beginning,” that Pope John Paul “did not live without fear; still less did he deny fear. Rather, he lived beyond fear, and his courage was an expression … of his faith.”

Indeed, over the course of his life he had to face most people’s worst fears.

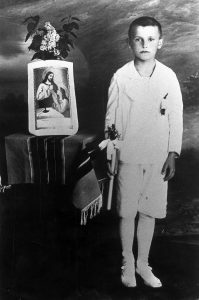

When he was 8 years old his mother died.

When he was 12 his only sibling, Edmund, died of scarlet fever.

When he was 19 his country was invaded and occupied by Nazi Germany.

When he was 20 he lost his father and was left without a family.

Through the Nazi years he belonged to a Church that was persecuted. His parish priests were deported to concentration camps, where 11 of them perished. During the war and afterward the young man took an active part in underground religious and cultural activities. He was part of the resistance.

When Poland passed from Nazi to Soviet domination, he lived for decades under surveillance. As a priest and bishop he was vulnerable. Members of the clergy and hierarchy sometimes “disappeared,” fell to assassination, or found themselves in prison on fabricated charges. Others had their reputations destroyed through false witness.

The young Karol Wojtyla knew danger, and he knew fear.

And from the moment of his election he, like every pope before and since, experienced the papacy itself as an occasion of fear. As pope he bore responsibility for a vast Church of more than a billion members, thousands of whom were suffering for the faith.

He bore responsibility for a clergy and laity grown lax in discipline since the free-for-all of the 1960s. He bore the burden of a man commissioned to speak for Jesus Christ on earth.

So when he said, “Be not afraid” — and repeated it — he was not dropping platitudes. He was speaking with the authority that comes from experience.

Just a few years before he was elected pope, he wrote a poem analyzing fear. He spoke of “the body’s fear / and fears for that body”; and he contrasted such instinctive, bodily terrors with “that fear / which is not against hope.”

He knew that utter fearlessness was not the goal. Fear, in fact, is essential to human flourishing. It is necessary for self-preservation. A truly fearless person would be insane.

But Karol Wojtyla — and later Pope John Paul — was able to order his fears. And he subordinated all earthly fears to the biblical “fear of the Lord.”

He spoke of this phenomenon in a General Audience just three weeks after his coronation as pope Nov. 15, 1978. He acknowledged that the virtue of fortitude “always calls for a certain overcoming of human weakness and particularly of fear.”

By nature, he added, human beings spontaneously fear “danger, affliction, and suffering.” Those who are courageous are those who “are capable of crossing the so-called barrier of fear, to bear witness to truth and justice.”

Such people, he said, can be found on battlefields, but also in hospital beds and deportation camps. Those who act rightly in spite of fear are “real heroes.”

Those who would be brave, he said, must go beyond their own limits and transcend themselves, facing risks in spite of anxieties and dangers. “The virtue of fortitude proceeds hand in hand with the capacity of sacrificing oneself. … For a just cause, for truth, for justice, one must be able to ‘lay down one’s life’ ” (John 15:13).

Going forward “beyond fear” was, obviously, very much on his mind as he began his pontificate.

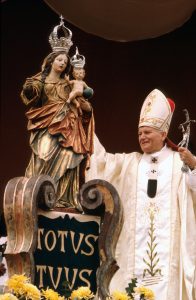

Years later, when asked about the source of his courage, he pointed to the Blessed Virgin Mary. He noted that, upon his mother’s death, his father took him on pilgrimage to a nearby Marian shrine. In later years, the little family made other Marian journeys at important moments in life. It was to Mary that young Wojtyla went during the Nazi occupation; he was appointed a leader in an underground youth movement called the “Living Rosary.”

When he was young he became interested in Marian apparitions, and he spoke of them as “a sort of ‘Be not afraid’ spoken by Christ through the lips of his mother.” He was convinced that, for Poland, victory would come “through Mary.”

As he began his pontificate — speaking those words against fear — he dedicated his life to her. He took as his motto the Latin “Totus Tuus,” which means “Totally Yours” and is addressed to Mary.

Mary was his strength. She herself had heard the message “Be not afraid” from the angel Gabriel. And she moved beyond fear, trusting in God to change history.

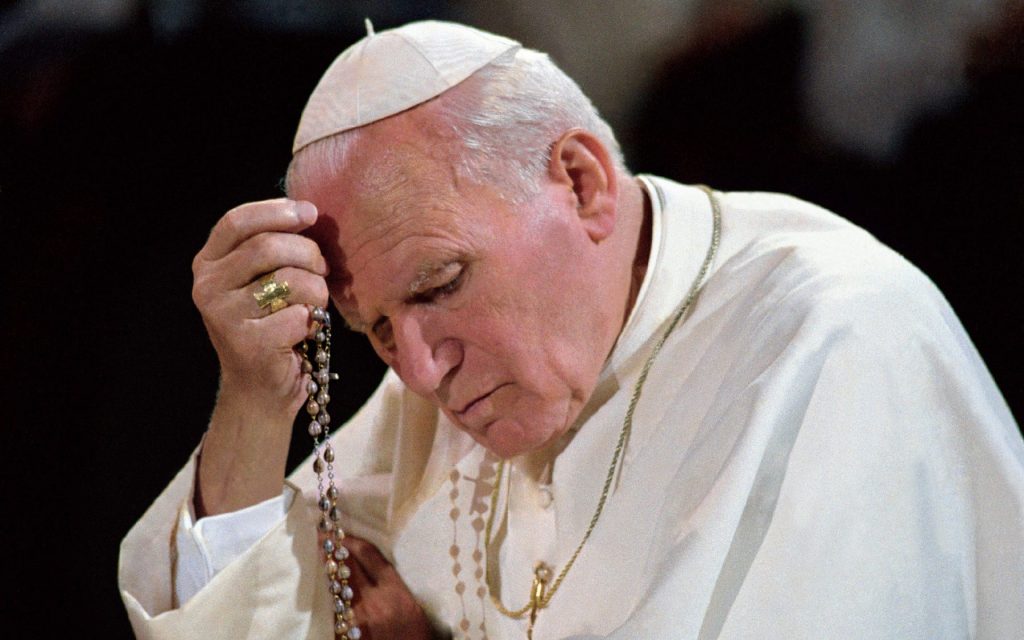

Pope John Paul punctuated all his daily activities with the rosary, fingering the beads constantly as he moved from place to place. He greeted thousands of guests per week, and he handed each of them a rosary.

On the feast of Our Lady of Fátima in 1981, he was shot and critically wounded by a would-be assassin in St. Peter’s Square. He later told Messori that, even then, he realized Jesus was telling him “Be not afraid” through Mary.

The subsequent years brought new fears. He was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, which affects the nervous system, causing stiffness and tremors. Gradually he lost strength and motor control. His strong voice became slurred. The ubiquitous cameras caught him drooling during public appearances.

He showed up anyway. He continued in his work until he could no longer continue, and then he died.

He was never fearless. Yet he moved beyond fear, for the sake of others, the innumerable others who looked to him.

And to the end, as they looked to him, he told them: “Be not afraid.”