“Catechism” comes from a Greek word meaning “instruction,” and such religious education has always been part of the Church’s life. St. Luke wrote his Gospel so “that you may know the truth concerning the things about which you have been instructed (kate¯che¯the¯s)” (Luke 1:4).

In the early Church most teaching was done out loud. There was no way to mass-produce books, and most people could not read anyway. Possession of Christian books was, moreover, a crime punishable by death.

Toward the end of the Roman Persecution (around A.D. 305), an African Christian named Lactantius composed the first summary exposition of Christian doctrine in his Divine Institutes.

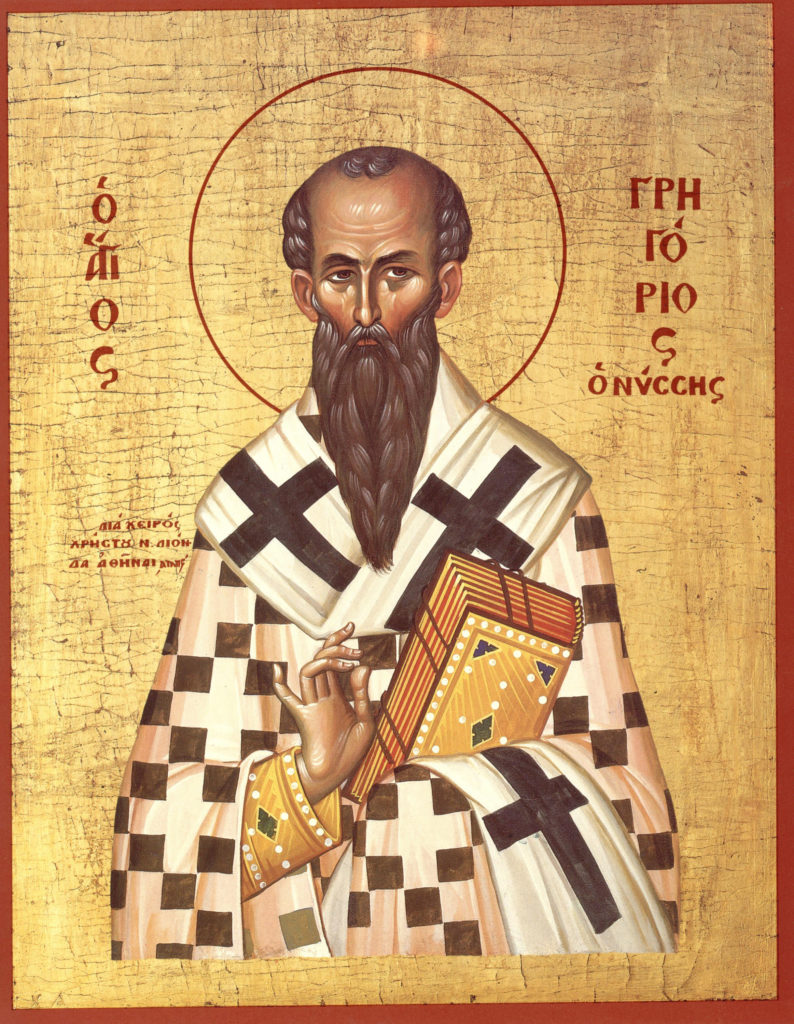

Not until the fourth century, when the faith was legalized, did the first true catechism appear. It was the Great Catechism composed by St. Gregory of Nyssa around A.D. 385. It was intended for instructors, and it served the purpose of a modern curriculum.

In the Middle Ages, similar books emerged, usually built around the Apostle’s Creed, the Lord’s Prayer, the Ten Commandments, and other numbered lists (works of mercy, deadly sins, virtues, sacraments, etc.).

With the invention of the printing press, around 1440, mass literacy — and mass instruction — became possible for the first time. There was great demand for religious books.

In the 1500s, with the Reformation, came the need to define true religion from false. In 1529, Martin Luther defined his religion against the Catholic Church’s doctrine, and he published his tenets in simple form in his bestselling Small Catechism.

Catholics soon countered Luther’s claims in their own catechisms. St. Peter Canisius produced one in 1555, and the Council of Trent promulgated the Roman Catechism in 1566.

The centuries that followed brought an explosion of literacy — and an explosion of catechisms. In 1885 the Baltimore Catechism first appeared in the United States, and it ushered in an unprecedented period of religious literacy in the Church. In England, the Penny Catechism had a similar effect.