The company of the first believers devoted themselves to the teaching of the apostles and the communion, the breaking of the bread, and the prayers (Acts 2:42).

The Mass is what the early Christians did. St. Paul’s letters are notable for their concerns about table fellowship. Later books of the Bible, Hebrews and Revelation, also take up priestly and liturgical matters. The Mass was defining for the first Christians.

But there was another distinguishing Christian act in the ancient Church: martyrdom.

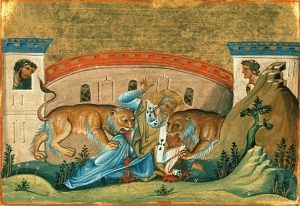

Martyrdom occupied the attention of the early Christians because it was always a real possibility. Shortly after the Catholic faith arrived in Rome, the emperor, Nero, discovered that Christians could provide an almost unlimited supply of victims for his circus spectacles. The emperors needed to keep the people amused, and one way to do so was by giving them spectacularly violent entertainments in the circus.

So the Christians were doused with pitch and set on fire, or sent to battle hungry wild animals and armed gladiators. Over time, Nero’s perverted whims settled into legal precedents, and the situation continued for centuries.

The Christians applied a certain term to their co-religionists who were made victims of persecution. They called them “martyrs” — “martures” — which means, literally, witnesses in a court of law. And to the martyrs they gave a reverence matched only by their reverence for the Eucharist.

In fact, the early Christians used the same language to describe martyrdom as they used to describe the Eucharist. We see this in the New Testament Book of Revelation, when John describes his vision of heaven. There, he saw “under the altar the souls of those who had been slain for the word of God and for the witness they had borne.” There, under the altar of sacrifice, were the martyrs, the witnesses.

That image brings it all together. For, in those first generations of the Church, the most common phrase used to describe the Mass was “the sacrifice.” Both the “Didache” and St. Ignatius of Antioch refer to it as “the sacrifice.” And yet martyrdom, too, was the sacrifice.

And so, in A.D. 107, when St. Ignatius described his own impending execution, he imagined it in eucharistic terms. He said he was like the wine at the offertory. He wrote to the Romans, “Grant me nothing more than that I be poured out to God, while an altar is still ready.” Later in the same letter he wrote, “Let me be food for the wild beasts, through whom I can reach God. I am God’s wheat, ground fine by the lion’s teeth to be made purest bread for Christ.”

St. Ignatius was bread, and he was wine; his martyrdom was a sacrifice. It was, in a sense, a eucharist.

St. Ignatius’ friend St. Polycarp also died a martyr’s death. St. Polycarp was bishop of Smyrna and had been converted by the apostle John. St. Polycarp’s secretary wrote a detailed account of the bishop’s martyrdom, and he described it, once again, as a kind of eucharist. St. Polycarp’s last words are a long prayer of thanksgiving that echoes the great eucharistic prayers of the ancient world and today. It includes an invocation of the Holy Spirit, a doxology of the Trinity, and a great Amen at the end.

When the flames reached the body of the old bishop, his secretary tells us that the pyre gave off not the odor of burning flesh, but the aroma of baking bread and incense. In yet another martyrdom, then, we find a pure offering of bread — a eucharist.

Such images recur in many other writings. The story of the martyr St. Pionius proceeds verbatim in the words of the eucharistic prayer: “and looking up to heaven he gave thanks to God.” In a similar way, the priest St. Irenaeus of Sirmium cried out, in the midst of torture, “With my endurance I am even now offering sacrifice to my God to whom I have always offered sacrifice.”

But what is it about martyrdom that makes it like the Mass?

Well, what has Jesus done in the Mass? He has given himself to us, and he’s held nothing back. He gives us his body, blood, soul, and divinity. And that’s love: it’s the total gift of self. That’s the very love the martyrs wanted to imitate. Jesus had given himself entirely for them. They wanted to give themselves entirely for him. If Jesus would become bread for them, they would allow the lions to make them wheat for Jesus.

Martyrdom was a total gift of self. The Eucharist was a total gift of self. In the Eucharist, Jesus gave himself to us. In martyrdom, we give ourselves back to him.

However, we know that very few of the ancient Christians died for the Catholic faith. There were perhaps thousands of martyrs — but the Church, even in the third century, had membership in the millions. What about the rest? How did they live the Eucharist?

For most of the early Christians, “martyrdom” came not with lions or fire or the sword. For most it consisted in a daily dying to self in imitation of Jesus Christ.

Jesus had told them: “If anyone would come after me, let him deny himself ... daily.” So the Christians denied themselves, in imitation of Jesus. They would never make a habit of eating lavishly as long as others were going hungry. They would never keep an opulent wardrobe while others dressed in rags. And they would never hold back their testimony as long as any of their neighbors were living in sin or in ignorance of the love of Jesus.

Whatever they had, these Christians gave. They gave of themselves — just as the martyrs gave themselves in the arena — and just as Jesus Christ gave himself in the Eucharist.

In Christ, they had come into a holy Communion. In baptism, they were baptized into his death — his martyrdom. In the Mass, they became one with him in the deepest, closest, most intimate bond possible.

This was, and is, the deepest truth of the faith. In Jesus Christ, we live as sons and daughters of the eternal Father — we share his own divine life. In Jesus Christ, we can call God our Father because God is eternally his Father. In the New Testament, St. Peter puts our holy Communion in the most powerful terms: We have become partakers of the divine nature (2 Peter 1:10).

And what is that nature? How does God live in eternity?

Christianity teaches that God is love. God is self-giving, life-giving love. This is the life the martyrs knew, especially at the moment of their death. But they themselves had been caught up into that life so long before and so many times — whenever they had joined with the Church for the teaching of the apostles and the communion, the breaking of the bread, and the prayers.

Jesus gave himself entirely to them, and they gave themselves in return. At every Eucharist, he gives himself entirely to us, and we give ourselves entirely in return. Father says, “The body of Christ,” and we say, “Amen.” When Catholics do that, we consent to the communion. We’re accepting the cross of Christ. We’re accepting our own martyrdom.

St. Paul signaled this in his Letter to the Romans: “I appeal to you therefore, brethren, by the mercies of God, to present your bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and acceptable to God, which is your spiritual worship.” Surely St. Paul’s words reached many future martyrs in Rome, where he himself would one day die by beheading.

But his words reached many others as well, men and women whose sacrifice would be something quiet and hidden and noticed only by God. St. Paul also referred to our bodies as “temples of the Holy Spirit.” In the ancient world, temples were not mere shrines; they were places of sacrifice.

And so are we. Our bodies are places of sacrifice, and our lives are the offering on the altar. We ourselves are the Mass in motion.

So our everyday life should be a voluntary sacrifice. Listen to the Church’s traditional language of penance and reparation, mortification, and fasting. It’s all about self-possession, self-denial, self-mastery. It’s good to be disciplined, and self-denial is a means to achieving discipline. But discipline, too, is a means and not an end. Why should we want to possess ourselves?

We possess ourselves in order to give ourselves away — just like Jesus, just like the martyrs. Only then can we truly become ourselves. For we are made in God’s image, and God is life-giving love, whose human life was a self-giving sacrifice. The Mass is that sacrifice, and all our lives must be placed upon the altar and taken up into the Eucharist — all the hours we spend at our desks or in the kitchen or in the field.

When we give ourselves without holding back, we are living like the early Christians. We are living like the martyrs. We are living the Eucharist.