When I read last year in Angelus that a professor at UC Berkeley had translated the whole of the Hebrew Old Testament by himself over the course of more than two decades, the news impressed me.

Sure, in terms of workload, St. Jerome and (embarrassed cough) Martin Luther did more, translating both Testaments into Latin and German, respectively. Most other Bible translations are the work of teams of scholars.

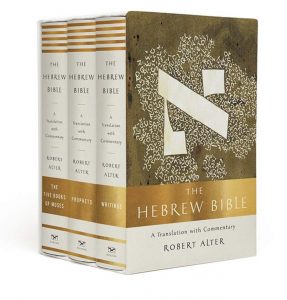

But I liked the boldness of Robert Alter, Ph.D.’s reasoning for making his own translation.

“There is, as I shall explain in detail, something seriously wrong with all the familiar English translations, traditional and recent, of the Hebrew Bible,” writes Alter, now 85, in the introduction to his three volumes, published in late 2018.

“Broadly speaking, one may say that in the case of the modern versions, the problem is a shaky sense of English and in the case of the King James Version, a shaky sense of Hebrew.”

My frustration with the ever-changing New American Translation, especially with some of the selections in the Lectionary, has caused me to take some undue pleasure in the lone scholar defying and decrying the work of so many committees.

However, it is especially Alter’s interest in what he calls “biblical narrative prose” that has convinced me of the worthiness of his effort. As a literary scholar, Alter is interested in the play of the language, what he calls the “semantic nuances and the lively orchestration of literary effects of the Hebrew.” At the same time, he wanted a version with “stylistic and rhythmic integrity as literary English.”

Naturally, such aspirations may sound a bit obscure and not for the popular reader. But the result of Alter’s labors gives a real energy to the stories of the Bible. His literary point of view is especially insightful with the narratives of Genesis. His commentary is not at all theologically sufficient for us who read the Old Testament with the perspective and wisdom of the New, but his appreciation of the literary merits and dynamics of the Hebrew Bible often illuminates.

It is a lie that Catholics were taught to ignore the Bible. Surely, throughout the centuries the Church worried about reckless interpretation, but always deeply respected and communicated the word of God. Just look at the art of the Gothic cathedrals whose stained-glass illustrations of the Bible are another kind of translation.

American and English literature in general is not understandable without reference to what the Canadian literary critic Northrop Frye called “the Great Code” — the Bible. Alter’s notes on the familiar Bible stories of the Old Testament include an appreciation of literary technique that I have sometimes seen in some treatments of the Lord’s parables, but not with the stories of the Old Testament.

The Bible, like all good literature par excellence, is what the ancients called “speculum vitae,” the mirror of life. This was painted on the ceiling of our seminary library in Cleveland.

The French existentialist Albert Camus noted that sometimes we look into a mirror and see a stranger. That is because we lack self-knowledge and mirrors are sometimes a bit too realistic for our tastes. The Bible is the mirror of human interaction with God and therefore reveals some of the less than beautiful parts of fallen nature.

My mother, may she rest in peace, was inspired by my constant harping to read the Bible from beginning to end (a yearly habit I have adopted from the classic Protestant spiritual repertoire inherited from my Lutheran relatives). I gave her a big print Bible and, while it took her longer than a year, she managed to read the Bible through, finishing less than a year before her death.

“Some parts of these stories are not so nice,” she said to me once. She was referring to the bloody descriptions of the Old Testament and the human sinfulness explicit throughout. The complexity of motivation confused her, as it should us.

An instance of this is the account of how Jacob and his mother, Rebekah, cheated Esau, Jacob’s older twin brother, of Isaac’s covenant blessing.

Genesis 27 recounts how Rebekah prepares a meal of kid goats for her blind husband, Isaac, who has asked Esau to hunt game for him. She then puts the skins on the arms and hands of Jacob, leading Isaac to mistake Jacob for his hairy older brother. Esau comes for his blessing only to discover Isaac has already given it to Jacob.

I always wondered about why the Bible would seem to hold up for esteem the ruse of the mother and son against the father and son. But even for this priest, the new translation’s commentary offers some worthy illumination on this aspect of salvation history.

Alter points out that Jacob’s later life included many deceptions. After Jacob had worked seven years to obtain the hand of Rachel in marriage, her father, Laban, substituted her sister Leah under the bridal veil, forcing Jacob to work another seven years in order to have the wife he desired. The father-in-law would go on to refuse Jacob the liberty he had negotiated in hard years of work.

But the cruelest deception Jacob the deceiver suffered was when his sons tricked him into believing that his favorite, their brother Joseph, was dead. Alter points out how as a literary device, the blood of a goat is sprinkled on the famous “garment” of many colors to convince the father of the loss of the son.

The kid goats cooked by Rebekah had earned the blessing; now, their blood was involved in the brothers’ duplicity. Millennials might call this “karma,” but Alter highlights it as literary irony.

(In a related discovery, Alter later notes how a second garment is stripped from Joseph, subtly recalling when his brothers took his coat of many colors from him, and used as evidence for a lie a second time in Egypt, when he is framed by the wife of Potiphar.)

Humankind has always loved stories. The stories of the Old Testament illustrate what St. John Henry Newman said about how we need others: “Persons influence us, voices melt us, looks subdue us, deeds inflame us.”

If that is the case, then Alter’s translation of the Hebrew Bible does an immense service in helping us read more deeply into the stories of Bible heroes. The style, with a repetitious flavor meant to convey a kind of cultural accent, helps with a simplicity that brings us closer to the basic human experience portrayed.

I experienced this in a few lines in the otherwise turgid and tendentious prose of Chronicles (it was written by priests; no further comment). In the first of those two books, there is a list of the 30 heroes (think ancient special operations soldiers) who accompanied King David. Three are singled out for special honor: Ishbaal, Eleazar, and Ahotite, who accompany David as he looks down at his native Bethlehem, held at that moment by Philistine forces.

David remembers the sweet water of the well at Bethlehem and says, “Who will give water to drink from the well of Bethlehem, which is by the gate?” The three heroes, with the audacity of youth, slip through the enemy lines and draw water from the well to bring to David. They risked their lives to satisfy their leader’s craving, showing both their bravery and the devotion David inspired.

That devotion is more understandable when we see what David does with the precious water.

“But David would not drink it, and he poured it in libation to the Lord. And he said, ‘Far be it from me before my God that I should do this. Shall I drink the blood of these men who have risked their lives? For at the risk of their lives they have brought it.’ And he would not drink it.” (I Chronicles 11: 18–19)

The episode reveals David’s character in various ways. He is nostalgic for the water he knew as a boy; he expresses his craving without dissimulation; and then he realizes how grave it was that a leader should expose his followers to such danger for a drink of water. Human weakness is on display here, as well as poetic nostalgia, but also magnanimity.

The account could be scripted for a dramatic biopic of David, but it also offers us a figure capable of learning from his mistakes. Studying the humanity of David can make us more humane.

As evidenced by the popularity of streaming TV — especially during the pandemic lockdown — our culture has a seemingly insatiable appetite for stories. If that’s the case, then the Bible should be a mine of treasures, except that we don’t need Disney+, Amazon, or Netflix in order to read the Bible.

The St. Newman quote about persons, voices, looks, and deeds is especially appropriate here: The Bible, and God’s gift of your imagination, can transport you to a different time and place and be able to gain wisdom looking in the mirror of humanity.

St. Jerome famously said, “Ignorance of the Bible is ignorance of Christ.” It is also, I might add, ignorance of humanity. Reading the Bible, especially by connecting with the stories contained in it, is a way to wisdom. We should not forget that Jesus the Teacher was Jesus the Storyteller of parables.

It is a mystery how in the Bible God inspired some writers to tell stories to move us. Reading those stories, savoring their details, meditating on them, can move us to be better disciples. Exposure to new translations, including and especially Alter’s unique achievement, should make us more grateful for the immense treasure we have.