In 1972, Father Hans Urs von Balthasar published an article about St. Thérèse of Lisieux in which he stated that “the fervor of veneration for her across the entire world has surely been fanned by the breath of the Holy Spirit.” He adds slyly, “Did not this little Thérèse have her hour at the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century? Someone has irreverently said that the Thérèse-boom is over for good.”

Yet, more than 50 years later, this clearly is not the case. Devotion to St. Thérèse of the Child Jesus and the Holy Face (the Little Flower), who in 1997 was declared a Doctor of the Church and was most recently the subject of an apostolic exhortation by Pope Francis, continues only to grow and increase, even exponentially.

But why? Von Balthasar responds, “Thérèse converts the grand ideas into the small change of everyday: in the ever-now moment she distributes love to God and to the people she meets.”

About the abyss

How is it possible for Thérèse to connect so deeply with so many? Father Bernard Bro, OP, in his classic text “The Little Way: The Spirituality of Thérèse of Lisieux” (Alba House, $14.95) offers an explanation: “Marx, Nietzsche, Freud: the three giants dominating modern thought. In fact the only way of appreciating Thérèse of Lisieux today is by adding her squarely to their company. It is the same battle, all along the line: man confronting the abyss. Here lies her genius.”

We’re well aware of “the abyss”: the seeming meaninglessness of life — the sense that things don’t add up and that my life doesn’t really matter. It is a misery compounded by profound loneliness, isolation, frustration, as well as the shame that comes from my sins. And if there is something “greater” in life to aspire to, I am not worthy of it, owing to my inadequacy — my defects, my nothingness, my lack. I don’t measure up. There is no place for me. I am not wanted.

But, you may ask, what can a sheltered young woman from a bourgeois French family who died at the age of 24 possibly know about “the abyss”? Remarkably, Thérèse is not the saccharine stereotype of so many holy cards and statues.

Consider this summary of the formative life experiences of the Little Flower:

- Traumatic loss: Thérèse’s mother died of breast cancer when Thérèse was only 4 years old. One of the first memories she describes is linked to her mother’s death: “I saw many things they would have hidden from me. I was standing before the lid of the coffin which had been placed upright in the hall. I stopped for a long time gazing at it.”

- Longing for the infinite: Young Thérèse experienced a deep desire for union with God — which some dismissed as implausible. Yet, at age 2, Thérèse “escaped” from home to go to Mass. She refused to go to sleep until she had said her prayers. She declared, “I too will be a religious.” Thérèse wrote in her autobiography, “At the age of three I began refusing nothing that God was asking from me.” Thérèse begged for entrance to Carmel at age 15 — even petitioning the pope personally.

- Abandonment: At the death of her mother, Thérèse’s oldest sister Pauline became her foster mother. But when Pauline departed to enter Carmel, the sense of abandonment devastated the young Thérèse. As she recounts, “In a moment I saw what life is really like, full of suffering and continual separations, and I burst into bitter tears. The weight of this suffering caused my mind to develop much too quickly, and it was not long before I was seriously ill.”

- Life-threatening illness: At age 10, the girl Thérèse, who had always been sickly, developed an illness so prolonged and severe that the family thought it would take her life: headaches of frightening violence, attacks of shivering, fits of great agitation. The child screamed in extreme fear, failed to recognize members of the family, had convulsions, tried to throw herself out of bed. Her sister Marie recalled, “She had frightful visions which froze the blood of all who had to hear her cries of despair.”

- Marginalized, maligned, and mistreated by her own community: As Thérèse was dying, one nun said, “Sr. Thérèse will die soon; what will our Mother Prioress be able to write in her obituary notice? She entered our convent, lived, and died—there really is no more to say.” Another nun referred to Thérèse as “certainly nothing special:” “She did not suffer from anything and was rather insignificant. Virtuous she certainly is, but that is no feat when one has so happy, uncomplicated a nature, not difficulties of character, and has not had to win virtue like us by struggles and suffering.” On her sickbed, one nun said to her directly: “If only you knew how little you are loved and esteemed in the house.”

- Prolonged spiritual aridity and suffering: From the moment Thérèse entered Carmel she began to experience what she called the “night of darkness:” “Complete aridity — desolation, almost — was my lot.” She told a nun, “I can assure you that I have not spent a single day without grief and struggle — not a single one!”

- An agonizing death: Tuberculosis had destroyed all but one small part of one lung so that Thérèse literally suffocated on her deathbed. The inner organs of her body began to putrefy with gangrene while she was still alive. And Thérèse on her deathbed was tortured with temptations to despair and to suicide.

All these experiences conspired to transform Thérèse into a saint of titanic faith, hope, and love. “She is with utmost intensity ‘one of us’,” declared Catholic writer Ida Friederike Görres.

Sanctity within our reach

The unabated allure of the Little Flower comes from her key conviction: “God does not call those who are worthy but those whom he pleases.” Thérèse convinces us that our nothingness is not a problem — it is a possibility:

“I see it is sufficient to recognize one’s nothingness and to abandon oneself as a child into God’s arms. It is impossible for me to grow up, and so I must bear with myself such as I am with all my imperfections. But I want to seek out a means of going to heaven by a little way, a way that is very straight, very short, and totally new” [The Little Way!].

Even those who struggle with nothingness possess a precious gift: desire!

“God has always given me what I desire or rather he has made me desire what he wants to give me. God cannot inspire unrealizable desires. I can, then, in spite of my littleness, aspire to holiness.”

Our greatest desire is for love. Thérèse confesses in a poem:

“I need a heart burning with tenderness,

Who will be my support forever,

Who loves everything in me, even my weakness…

And who never leaves me day or night.”

But what about our actual sins? Therese replies, “To be little also means not to lose courage on account of one’s fault, for children often fall, but they are too small to hurt themselves seriously.” For “in its audacious trust in God, the soul believes that it will more fully attract the love of One who did not come to call the just but sinners.” In the process, “Jesus opens his heart to us. He forgets our infidelities and does not want to recall them. He will do even more: He will love us even better than before we committed that fault.”

Yes, suffering is essential to this love for “to offer oneself to love as a victim does not mean accepting sweetness and consolation; it means exposing oneself to all anguish, all torment, all bitterness, for love lives only on sacrifice; and the more we would deliver ourselves up to love, the more we must offer ourselves to suffering.”

What sustains us is a healthy self-knowledge: “There is always present to my mind the remembrance of what I am. I am astonished at nothing. I am not disturbed at seeing myself weakness itself. On the contrary, it is in my weakness that I glory, and I expect each day to discover new imperfections in myself.”

The fruit of all this is genuine saintliness:

“Sanctity consists in a disposition of the heart which allows us to remain small and humble in the arms of God, knowing our weakness and trusting to the point of rashness in his fatherly goodness.”

Why a Doctor of the Church

When Thérèse was declared a Doctor of the Church, a friend of mine was granted an interview with Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, and he asked about the Church’s decision. The cardinal responded that Thérèse represents a new kind of Doctor — one who propounds a “theology of experience.” Her genius is in teaching that being a saint means letting the Lord work in us. Thérèse offers a profound interpretation of the doctrine of redemption: Redemption consists in giving ourselves into the hands of Jesus. The Little Way constitutes a very deep rediscovering of the center of Christian life.

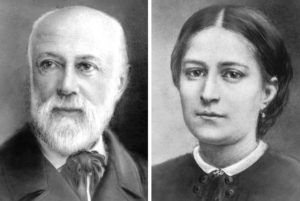

Görres recalls attending a Youth Movement meeting in Germany where a student showed her a photograph. He said, “This is the true appearance of Little Thérèse. Dom Willibrord Verkade, the monk-painter of Beuron, discovered and published it” (it was not one of the retouched, romanticized images of the Little Flower popularized after her death). Görres recalls that a small group of young people gathered around the student, and the photo was passed from hand to hand in stunned silence. Then someone said: “…Almost like the face of a female Christ.”