Even though I consider myself pretty Catholic, I have avoided the Stations of the Cross for most of my life.

I had what you might call a tumultuous childhood that left me with an odd form of self-diagnosed post-traumatic stress disorder. Even today, there are times when I’ll be walking down the street only to flinch or dodge an imaginary blow that just isn’t there; call it bad memories or phantom pain, but it’s real and unsettling.

Though I knew there were people out there who suffered worse than I did, I still wanted nothing to do with meditations or prayers that had to do with suffering and misery. Give me the Joyful and Glorious mysteries of the rosary — those were more my speed. Keep the sorrowful stuff to yourself, Lord.

As we learn of more and more people around the world losing loved ones to the coronavirus (COVID-19), I’m reminded of an experience that happened to me some years ago. I was alone with my grandmother in her hospital room. I was watching her die.

Though I kept a strong face, I was sad, disoriented, frightened, and confused. For much of my life, my Nana (sometimes “Nana Banana,” a nickname I gave her when I was a small child) was a second mother for me, a lighthouse in the tempest.

She was always there with a smile, some words of encouragement, or a small bag of my favorite pretzels (my snack of choice after school for many years).

Though she lived simply, she struggled her whole life, always on the verge of poverty, always dealing with uncertainty. When her husband, Harry, my grandfather, a gravedigger for more than 30 years, died of a heart attack when I was 22, it became my turn to take care of her.

I was just starting in my career in publishing, busy with work, and making new friends at my new job. Still, I would see Nana every day, take her to the grocery store on Saturdays, primarily to get cat food (I swear her cats ate more food than she ever did) and to Calverton National Cemetery once a month to visit Harry.

At the time, I was driving an old Jeep CJ-7, and in the summer we’d take off the hard-shelled roof and cruise down the Long Island Expressway en route to the old flower shop she loved so much; there we would buy the perfect bouquet of cash-and-carry carnations to put on my grandfather’s grave.

Nana. We were pals. We were, in many ways, best friends.

The last five years of her life, though, had become even more of a struggle than the first 78. She suffered a series of strokes and became bedridden. Her daughter, my aunt, who had struggled her whole life with addiction, became her primary caregiver.

During those final years, because of various complicated circumstances, I didn’t see my grandmother very much. We would talk on the phone from time to time, but visits were almost impossible.

I missed those old days when we were BFFs, blasting Bruce Springsteen on the radio while she wore big bug-eyed sunglasses, giving people the peace sign as we cruised to the grocery store to buy kitty litter.

But here she was now, so close to death. She couldn’t speak. Her hospital room was quiet except for the beep of the heart monitor and her own labored breathing. I knew I was going to lose her, and I knew I was going to lose her soon. I took her frail, soft hand into mine and just held it as I looked into her pale water-blue eyes.

For a fleeting moment, I felt her whole life flash in front of me. Wait, I thought afterward, isn’t that supposed to happen when I die?

But at the moment I felt as if all her stories — growing up in Brooklyn, her walks on the boardwalk at Coney Island, all the five-cent Pepsis she bought as a teenager, the death of her father when she was 21, the loss of her first love, working at Woolworth’s during World War II, the disappointments she suffered, the joys she experienced — had all been downloaded through the palm of my hand and into my heart.

No words were spoken, but just being in her presence while she was suffering made me feel closer to her than I had ever felt before.

Nana would die a few days later. I wasn’t in her hospital room when it happened, but to this day, I carry her life around inside me, and I am a better person for it. Having been there with her during those painful and precious moments created a bond and an understanding that continues to affect my life. I know that today in this time of pandemic, many people do not get that opportunity.

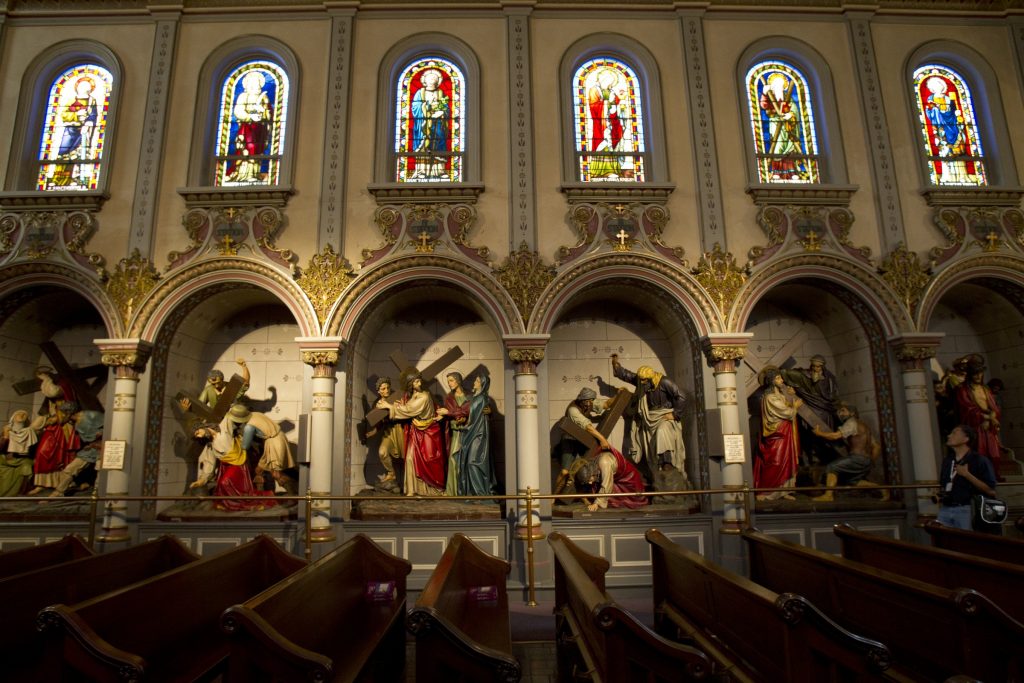

Sometime later, after her funeral, I was drawn to the Stations of the Cross. I don't know why. I just remember being in church and looking at the stained-glass depictions of Jesus’ last moments. I thought of my grandmother and her struggles, and I looked at the colorful images as the sun streamed in, casting an aquarium of colors on the floor.

I realized that just as I had felt close to my grandmother as she made her way to God, I felt closer to Jesus as I spent time with him as he inched his way to God. I’d never felt that before. It was late summer, and I remember asking myself why the Stations were relegated to Lent, when suffering is around us all the time. Soon after that, I made the Stations a regular spiritual exercise.

I love the visual representations of Jesus’ life. As a movie geek and someone who attended film school for a couple of years, I sometimes look at the Stations of the Cross as if I were watching a movie while listening to the director’s commentary. Only this director isn’t Martin Scorsese or Steven Spielberg; it’s God talking to me through prayer.

As Christians, we celebrate Jesus’ passion every year, so we may fall into the trap of thinking that we know the story, like, “Hey, I’ve seen this movie before; I know what happens.”

But there’s so much more going on that we might not know. When we meditate on the Stations, no matter what time of year, no matter what we are going through, we allow God to speak to our suffering, to provide us with insight on what unfolded 2,000 years ago and what’s unfolding in our very lives today.

The Stations of the Cross isn’t just a Lenten practice, it is a perennial exercise in spiritual awakening and a vital way of helping us carry our cross — and the crosses of those around us — in this time of uncertainty and upheaval.

For a limited time, the ebook of “Station to Station: An Ignatian Journey Through the Stations of the Cross,” by Gary Jansen, is available for free to help people during this time of pandemic. Copies are available at Amazon.com, BN.com, or Apple.com.