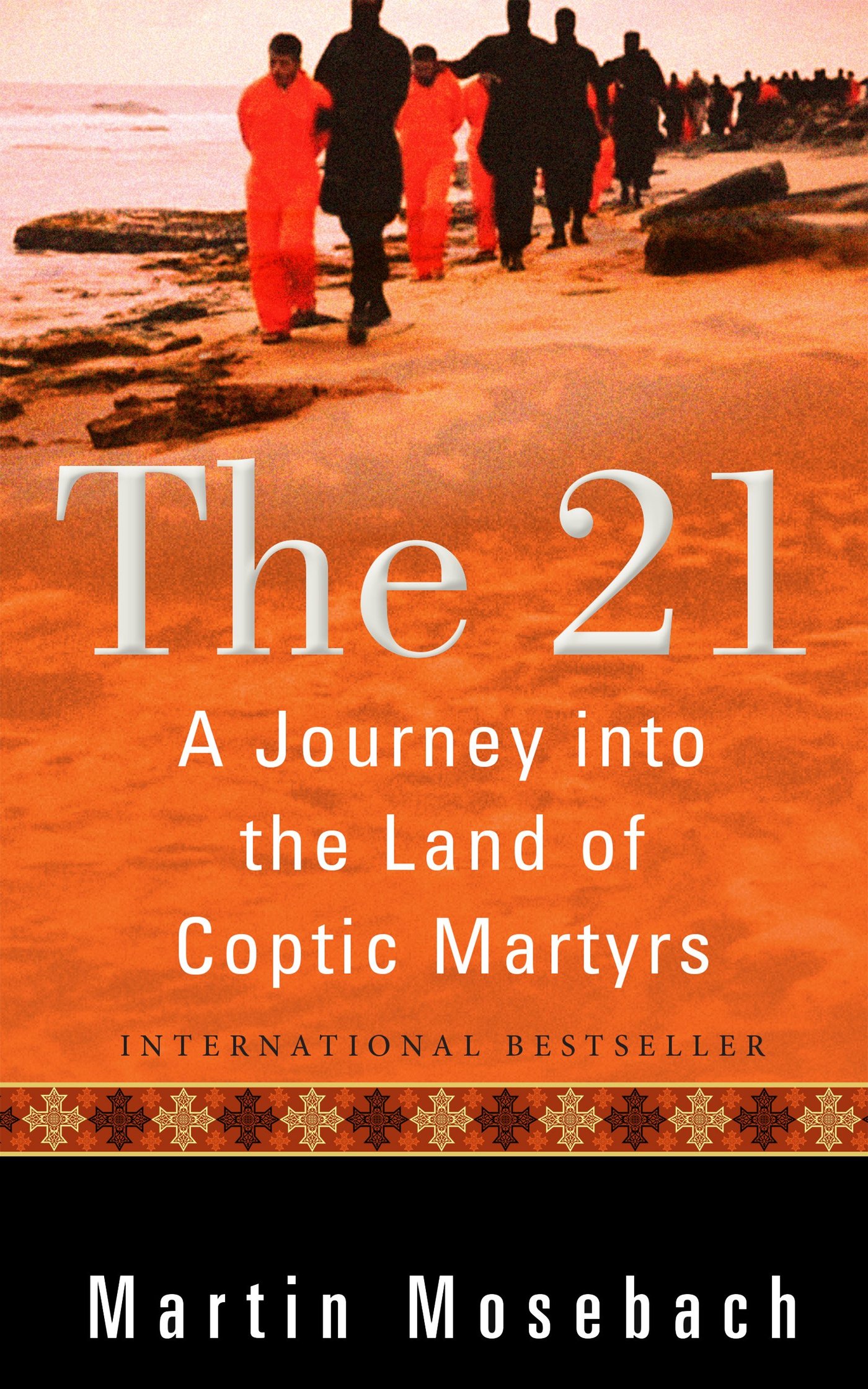

Martin Mosebach saw an unusual magazine cover photo of a young man, and as a result wrote an exceptional book. The magazine was called Vatican and the photograph was quite controversial since it was cropped from an ISIS video of the young man’s decapitation with 20 other mostly young men on the shores of the Mediterranean in Libya.

The man is now called “Saint Kiryollos,” and he and his companions were executed by masked terrorists because they would not renounce their faith in Jesus Christ.

The date was February 2015, in the aftermath of the so-called Arab Spring. With the collapse of the Gaddafi regime in Libya, the country went into chaos.

Three years after the infamous Benghazi embassy attack, ISIS released a report on the internet that 21 Christian construction workers had been captured in the Libyan city of Sirte. Their death was threatened as a reprisal to the Coptic Church of Egypt for the alleged kidnapping of Muslim woman.

Three days later, ISIS broadcast a video of the decapitation of 21 men. A caption running below on the screen said the captives were, “People of the Cross, followers of the hostile Egyptian Church.” (In fact, while 20 were Egyptian Christians, one of the men was from Ghana.)

There were swift reactions to the killings. Egyptian General and President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi ordered airstrikes against ISIS in Libya the day after the video appeared and announced seven days of national mourning. The United Nations Security Council, Pope Francis, and the Obama administration all conveyed their sympathies.

Mosebach, an acclaimed German author who has won many literary awards. became intrigued by “these poor farmers” two years after the killings and asked himself, “Was there anything in their villages that might have foreshadowed all this?” He was led to write this beautiful and moving book, “The 21: A Journey into the Land of the Coptic Martyrs.”

He is an intellectual, a man of letters who is very interested in theological themes, particularly the liturgy. He has published articles in The New York Times about Pope Benedict XVI and essays in First Things.

“The 21” is his first nonfiction work, a mixture of hagiography (writing about the saints), history, travelogue, cultural analysis about secularism in Europe compared to the perspective of most of the people he met in Egypt, an indirect criticism of Roman Catholic leadership and lack of fervor, and an almost reverent appreciation of the deep practical mysticism lived by the Coptic Christians.

He has a novelist’s eye for detail. The houses built for the families of the martyred saints by the Egyptian government are of concrete block, large but unfinished. In contrast to the simple houses of clay that were traditional, they do not seem to fit the lifestyle of the people.

Cattle and pigs are assigned a room in the new houses, which are bare of furniture except in the “salon,” which resembles a sultan’s throne room. Pictures of the martyrs hang on the wall, all photoshopped with what appear to be cartoon crowns above their heads. The church ordered to be built by el-Sisi looks like a “nuclear reactor.”

In El-Aour, the home village of 13 of the saints, the writer tells of going to the church where young people pray, even when there is no liturgy scheduled, the women on one side of the space before the “hurus” — the velvet curtain that is the Coptic version of the “iconostasis” (“icon stand”) of the Byzantines and Orthodox — and the men on the other.

Mosebach thinks that the parish priest was bewildered by the canonizations of the men of his village. I can imagine myself in the pastor’s situation as he said, “You have to understand these were average young men, completely normal guys. I never would have thought they would become saints!” Mosebach comments, “It still perplexed him — if only he had known.”

Some were illiterate, some married, one just engaged, all of them, like so many immigrant workers away from home, trying to earn money to send back as much as they could to their poor families.

They worked construction, lived together in a house where they all slept side by side on the floor. Coptic priests visited them and celebrated Mass for them occasionally until a year before their death.

Mosebach spoke to those priests, also, one of whom commented on the martyrs by saying, “Every Christian must have a cross — a real one and a symbolic one, and both must be present. Every Christian must live the life of Jesus anew. Christians in Egypt have always understood this, and that is why Christianity is so strong in Egypt.”

I could not help wondering, “It is?” as I read the words. Mosebach had already noticed that Coptics in Egypt, even women, tattoo a cross at the base of their thumbs so that they never can hide their attachment to the cross.

ISIS called them “People of the Cross,” although the terrorists did not distinguish much between Copts and Roman Catholics. The executioner who speaks in the ISIS video, in English, also says that they will conquer “Rome.”

Mosebach was able to glean very few individual details about the martyrs. Like the official icon of their canonization, where the faces of the men look much the same (with the exception of Matthew, from Ghana), there is not much to differentiate them. The latter, although not a Copt, is supposed to have said, “I, too, am a Christian,” to the terrorist captors.

The descriptions Mosebach quotes of the Egyptians are more than concise:

-

- “He was quick to forgive, argued with no one, and was faithful and honorable.” (Magued)

-

- “He served his whole family.” (Hany)

-

- “He was friendly and had a kind heart.” (Ezzat)

-

- “He slept with the Bible on his chest. He prayed and strictly followed the fast.” (Malak)

-

- “His peaceful smile showed how close he was to God.” (Luka)

-

- “He gave alms even though he was poor.” (Sameh)

-

- “He carefully considered his words before opening his mouth.” (Milad)

-

- “He was discreet, respectful, and calm.” (Issam)

-

- “He was calm, obedient, and quick to confess.” (Youssef)

-

- “He devoted a lot of time to helping the ‘Lord’s brothers’ — the poor.” (Bishoy)

-

- “He was a man of prayer and liturgy.” (Girgis the Younger)

-

- “He was a quiet man, even when criticized.” (Mina)

-

- “He was an honest worker and treated his parents with respect.” (Kiryollos)

-

- “His heart was pure and simple, his words humble.” (Gaber)

-

- “He was compassionate and strove to help others.” (Girgis the Elder)

Oh that our lives could be summarized by such succinct virtue!

Although I would like very much to visit Egypt, I think I never would have seen all the things Mosebach was able to see.

What he has written is a meditation on the profound sense of prayer he found in the Coptic Church, the depth of mystery in her liturgy, the valor of the witness of a minority that has been persecuted for 1,400 years, the reality of faith to be experienced in the poor and the powerless.