Though he was struggling with poor health, Pope Francis announced last November that he planned to visit Nicaea (Iznik, in Turkey) in 2025.

Pope Leo, soon after his election, voiced his intention to fulfill that plan of his predecessor.

Why were both men so determined to go as pilgrims to a Muslim city that hasn’t had an active Christian community in more than 100 years?

Because in that place, in A.D. 325, a united Church laid the doctrinal foundations for believers in every age to follow.

Iznik is in the news this year because 1,700 years have passed since the Council of Nicaea. Pope Francis made the observance of this anniversary a keynote of the Jubilee Year of Hope, and Church leaders have expressed great expectations for what might be accomplished in 2025.

In its original historical moment, the Council of Nicaea was an occasion of hope — especially for the Emperor Constantine.

It had been 13 years since he took the imperial throne in Rome. Within months of his conquest, early in 313, he issued the Edict of Milan, which legalized Christianity after centuries of Roman persecution. Constantine hoped that religious freedom would help him achieve unity and peace throughout the empire.

Though Constantine had not yet undergone baptism, he gave credit for his victories to the Christian God. As ruler of the Western Empire, he took an active interest in Church matters. He was bothered by disagreements among Christians and worried about their potential for causing political instability.

He urged bishops to meet in councils to bring an end to disputes. In North Africa, Christianity had been rent by schism since the time of persecution. From a distance, Constantine summoned three councils there.

He also sponsored councils in Spain and Gaul (modern France) and spared no expense in encouraging attendance. Each bishop received free transportation — a carriage big enough to hold the prelate and his entourage.

Constantine judged these regional councils to be successful, and he was pleased to see bishops cooperating and coming to consensus.

Meanwhile, his own power grew. The empire had been designed for rule by four men, a Caesar and his deputy in the West with a corresponding duo in the East. In the year 324, however, Constantine seized control of the Eastern lands and declared himself sole ruler. He was determined to bring unity to the Roman world, the better to ward off its enemies.

He was appalled, however, to find the Eastern churches in a virtual state of civil war — divided over the novel doctrine of a man named Arius.

A priest of Alexandria in Egypt, Arius preached that the divine Word (see John 1:1) was not God in the same sense that the Father was God. From scattered Scripture verses, Arius argued that the Son of God was neither coeternal nor coequal with the Father.

Thus he denied the full divinity of the Son of God, whom Arius described as a creature, though the greatest of all creatures.

Arius was skilled at preaching, and he had a knack for summarizing his doctrine in slogans, which spread rapidly like the common cold. One popular ditty went: “There was when he was not” — that is, there was a time when the Son did not exist.

The bishop of Alexandria, named Alexander, condemned Arius for undermining the most foundational Christian tenets: the Trinity and the Incarnation. Such beliefs had long been enshrined in the liturgy and attested by the Fathers.

So Arius was banished. But that left him free to travel and make alliances among other leaders in Church and government. He gathered support, but also roused opposition. Soon, his doctrine was dividing congregations in many lands. There were disputes over Church property. Neighboring bishops were divided over how to handle the situation.

In such matters, Constantine, through all his years of ruling, had drawn upon the counsel of a Spanish bishop named Hosius of Cordoba. During the final years of Roman persecution, Hosius had suffered for the Faith and remained steadfast. Historians believe it was he who first persuaded Constantine to commit himself to the Christian God. Hosius had organized the regional councils that were dear to the emperor.

But now the stakes were higher. Arius’ claims struck at the doctrine of God. And the problem was international, not regional.

Hosius proposed an unprecedented event — a Church council that would be universal. Constantine agreed and chose to host it close to his own summer home, in the city of Nicaea, where his influence might be stronger.

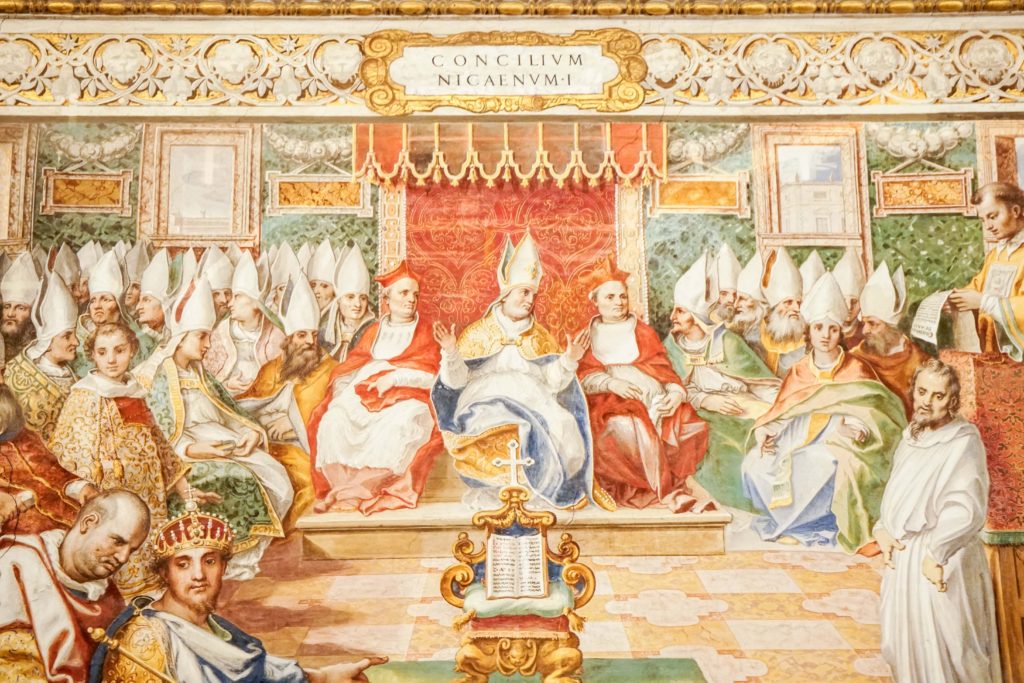

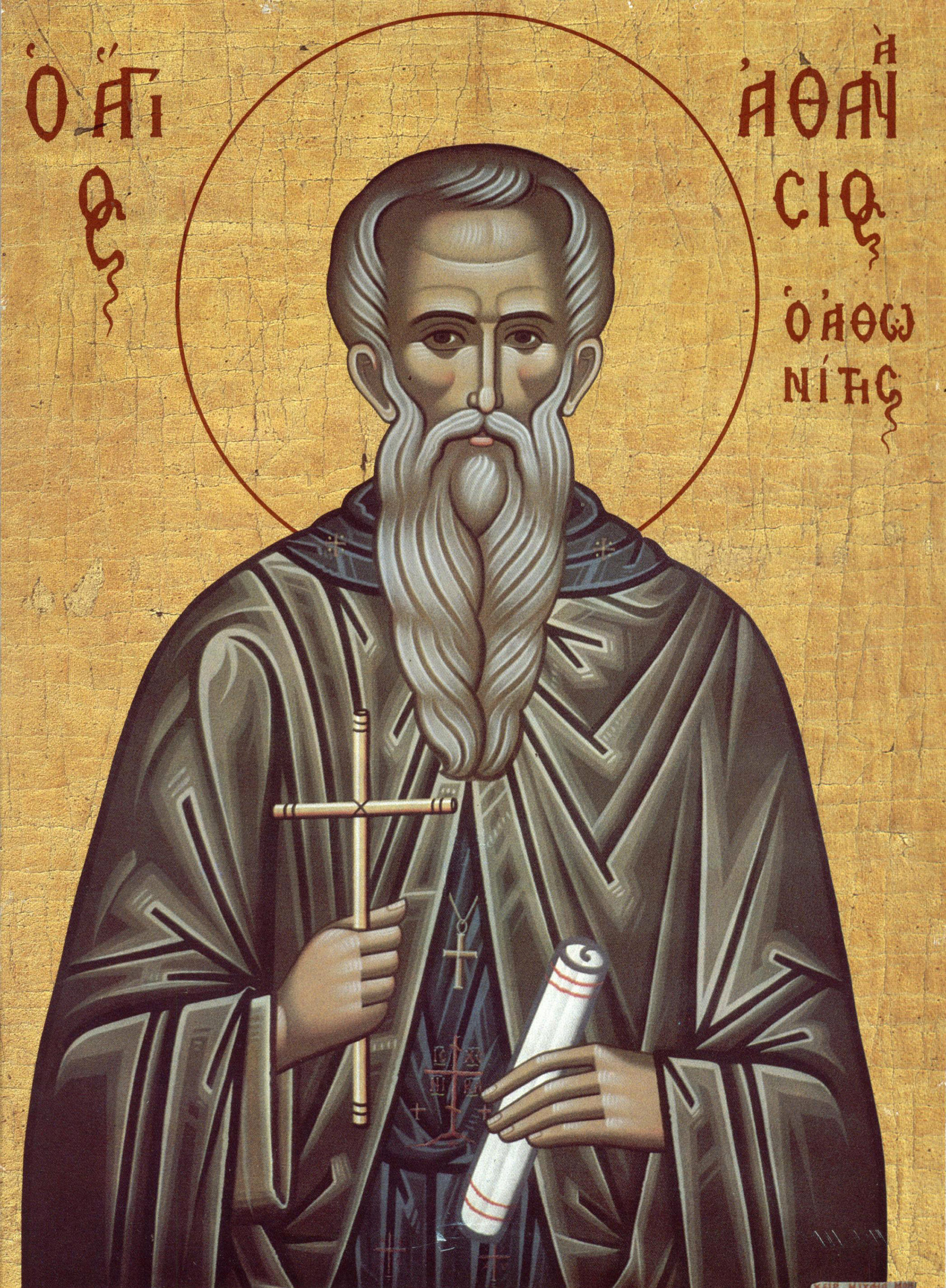

The council convened in mid-May of 325 and closed a month later. The published proceedings filled 40 volumes, though none of them has survived. Most of what we know about the Council of Nicaea is what we glean from the accounts of two eyewitnesses: Eusebius of Caesarea, who had sympathies for Arius, and Athanasius of Alexandria, who was a young theological adviser to Alexander of Alexandria.

The bishops gathered with great ceremony. Athanasius testified that there were 318 in attendance. Most were from the East, though the pope sent two representatives, as he was too old to travel.

Last to enter was Constantine himself, his robes glittering with gold and gems. He humbled himself by venerating the old bishops who had suffered and still bore wounds from persecution.

The emperor began with a speech thanking God for the realization of his desire: a meeting of the bishops of the universal Church.

Then the floor belonged to the bishops — who immediately broke out in a verbal brawl. According to Eusebius, “some began to accuse their neighbors, who defended themselves, and recriminated in their turn. In this manner numberless assertions were put forth by each party, and a violent controversy arose at the very commencement.”

The cacophony at Nicaea is sometimes portrayed as a conflict between Apostolic Tradition and the Arian heresy. But it wasn’t that simple. Some bishops thought it imprudent to describe the mystery of God. They preferred to stick with language found in Scripture. Others opposed Arius, but were uneasy with the language used to condemn him. Still others would gladly use anything handy to cudgel the man.

According to Eusebius, Constantine patiently listened. And he skillfully — over the course of weeks — guided the discussion toward consensus.

It was Constantine himself (say our witnesses) who first suggested use of the Greek word homoousios to describe the relation between God the Father and the Son of God. Homoousios means “consubstantial.”

The term met resistance from several bishops. But as they deliberated, it became clear that no term did the job as well.

In the end, the Fathers of Nicaea crafted a profession of faith tuned precisely to their doctrine.

We believe … in one Lord Jesus Christ, the Son of God, begotten of the Father … Light from Light, true God from true God, begotten, not made, consubstantial with the Father.

Arius was exiled.

Then the bishops moved quickly through other business. In the end, the Council Fathers published 20 canons that laid down law on matters great and small.

They imposed a common date for the celebration of Easter. They set a minimum time for preparation before adult baptism. They forbade priests from cohabiting with women other than their mothers or sisters. They insisted that at least three bishops should be present at the ordination of a bishop.

These are important disciplinary matters, but they pale in significance and authority before the doctrinal content and binding power of the creed, which is today recited at most Sunday Masses.

The council had solved the Church’s besetting problem, achieved consensus, and brought about unity.

That doesn’t mean it found an easy fix. Arianism would wither for centuries before vanishing.

We look back on Nicaea from the comfort and clarity of a developed theology of Church councils. We know conciliar authority, and we respect it.

But the Fathers could not consult centuries of history and reflection. They made that history. Nicaea was the first of the General (or Ecumenical) Councils. The Catholic Church has convened 20 more since then.

So it’s easy to see why Popes Francis and Leo have wanted to go to Nicaea as pilgrims. And it’s understandable that they have harbored great hopes for the anniversary. Some of the old issues have returned to trouble us again — like the ancient dispute over the date of Easter. But we’ve added plenty of new problems, too, and they need to be remedied before all Christians can share communion.

History teaches hope. Pope Leo has learned that lesson.

He said in May: “My election has taken place during the year of the 1,700th anniversary of the First Ecumenical Council of Nicaea. That Council represents a milestone in the formulation of the Creed shared by all Churches and Ecclesial Communities. While we are on the journey to re-establishing full communion among all Christians, we recognize that this unity can only be unity in faith. As Bishop of Rome, I consider one of my priorities to be that of seeking the re-establishment of full and visible communion among all those who profess the same faith in God the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit.”

That is the faith of Nicaea.