My spiritual reading for Lent this year was a book by a Spanish saint who proposed a novel idea: that we should be so involved and engaged as we read the Gospels that we become virtual participants in them.

As I explained this initiative to my parishioners in my homily for Palm Sunday, one of my applications of this was that, inserted in the narrative, we relate to the other actors in the drama of our salvation. That included for me Barabbas, I said, because we have something in common with him.

Barabbas was guilty and was set free, while Jesus was innocent and condemned to die. Likewise, we are the guilty ones and Jesus, the innocent one, died for us.

As I was preaching, I brought to mind an old Hallmark special TV drama about Barabbas that fascinated me as a boy. A woman after Mass told me that there had also been a movie about Barabbas based on a book that was much better. She couldn’t recall the name of the book, only that the author was Scandinavian.

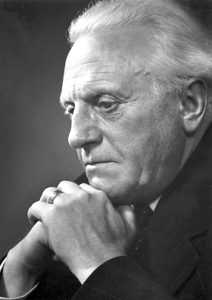

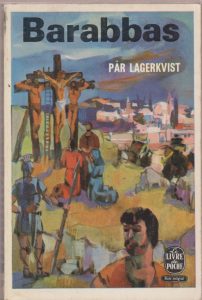

That clue was enough to lead me to find the book online, where I was able to download it from my local library. “Barabbas” is a very short novel by Swedish writer Pär Lagerkvist published in 1950. I was surprised to learn that he was a Nobel Prize winner for literature and professedly an unbeliever, though he had been raised a devout Lutheran.

But Lagerkvist was not a hostile unbeliever. The novel itself seems to be a kind of wrestling match between belief in Jesus and doubt. Barabbas, who was portrayed by Anthony Quinn in the movie version, is described as a rough customer, a violent man, with a scar on his face that is revealed as a strange symbol of the tragedy of his life.

The Gospels say nothing about him after he is released to freedom by Pilate, but Lagerkvist imagines the ex-prisoner is driven by an impulse to follow the crowd to Golgotha.

He spies Jesus on the cross, interprets the Blessed Mother’s sadness as including the idea that she held her Son somehow responsible for his fate, experiences the famous darkness at noon, and then holds a secret vigil at the tomb, which took place after a drunken tryst with a mistress and an enigmatic meeting with St. Peter.

The novel tells how Barabbas misses the moment of the Resurrection, somehow, but sees the empty tomb and is given an account of it by a woman only identified by her cleft lip. His relationship to her is revealed when she is stoned as a heretic for giving witness to Jesus’ resurrection.

He is confused by what has happened to him and to Jesus and, almost unwillingly, he gets involved with the early Christians. Lagerkvist imagines the man’s thoughts and his version is compelling:

“They spoke of his having died for them. That might be. But he really had died for Barabbas, no one could deny it! In actual fact, he was closer to him than they were, closer than anyone else, was bound up with him in quite another way. Although they didn’t want to have anything to do with him. He was chosen, one might say, chosen to escape suffering, to be let off. He was the real chosen one, acquitted instead of the son of God himself — at his command, because he wished it.”

Barabbas is attracted to the nascent Christian community because of his own strange “relationship” with the Crucified One, but he is repulsed by Jesus’ death. He cannot understand why anyone would want to suffer, much less adore someone who did so. His ambivalence makes him decide to reject the Christians one day and return to them on the next.

The novel has imaginative power. The bandit who was saved from crucifixion and set free goes back to banditry. His fellow bandits are frightened of him and notice the change in him since his captivity in Jerusalem.

His journey takes him to several different places before ending up as a slave in the mines of Cyprus, where he is shackled to a man who has heard of Jesus the Christ and prays to him. Barabbas tells the prisoner, Sahak, that he was a witness both to the crucifixion and the resurrection but does not mention that he was set free in exchange for Jesus.

Their bond leads to their release from captivity, but Sahak is eventually discovered as a Christian and put to death. Barabbas, who tells the governor he only wanted to believe in Jesus but could not, is spared. The governor then takes him to Rome in his retirement, where Barabbas hears about clandestine Christian gatherings and even attempts to go to a Eucharist in the catacombs.

When Nero sets Rome on fire, Barabbas is caught up in the rioting and thinks that the Christians are burning the city because Jesus has returned. He is captured and imprisoned with the Christians, including St. Peter, who recognizes him from their strange encounter in Jerusalem.

The other prisoners are horrified that Barabbas had told the judge his violence was an expression of belief in Jesus the Christ and, although St. Peter speaks to him kindly, he is avoided by the others as they all await execution and, even when crucified, is located at a distance from the others.

Faith still eludes him and he cannot understand the God of love that the Christians speak about and pray to. André Gide, who wrote the foreword for the edition of the book that I read, found the ending of the book to be particularly moving.

“The closing sentence of the book remains (no doubt deliberately) ambiguous: ‘When he felt death approaching, that which he had always been so afraid of, he said out into the darkness, as though he were speaking to it: — To thee I deliver up my soul.’ That ‘as though’ leaves me wondering, whether, without realizing it, he was, in fact, addressing Christ, whether the Galilean did not ‘get him’ at the end. Vicisti Galileus [“You have won, Galilean”], as Julian the Apostate said.”

Sounds like my idea of a happy ending: God wins.

And so, a casual remark in my Palm Sunday homily made it so that I spent Holy Week this year with Barabbas. He is a man worth thinking about. The famous Christian teacher Origen thought that the man released instead of Our Lord might have been named Jesus Barabbas. He saw the last name as an Aramaic reference to “bar” (“son”) and “abba” (“father”). So one Son of the Father was the reason another was set free.

The seemingly endless irony of the figure of Barabbas gives us something to meditate about. The novel-parable was a spiritual “vade mecum” (“handbook”) for me this year. The enigmatic ending can be interpreted as the dying man’s redemption. Lagerkvist’s Barabbas took the leap of faith as he left this world. He became another witness of the Resurrection, a difficult witness, as the lawyers might like to say, and a tortured one.

And for me, I might add, a very convincing one, because many of us struggle like him.