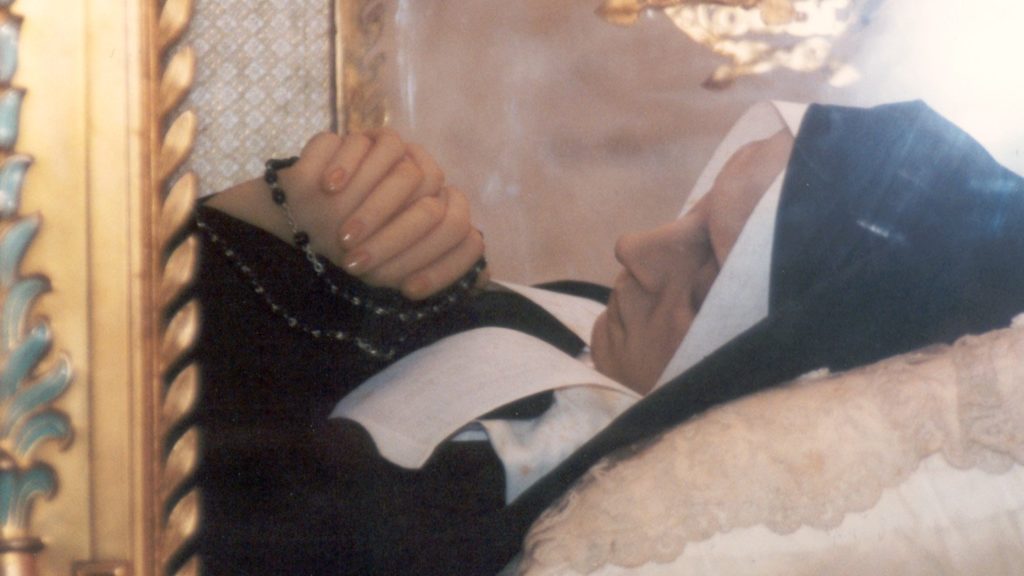

In his travels, Michael S. Carter remembers encountering the bodies of several saints considered incorrupt or resistant to natural decay.

"It's just so unique to behold a person that lived centuries ago with whom we can feel a connection through our faith life," the associate professor of history at University of Dayton in Ohio said.

Carter and other experts in philosophy, science and theology spoke with OSV News about incorruptibility, addressing everything from incorrupt saints and their significance in the Catholic Church to the relationship of faith and science.

Dozens of saints or people on the path to sainthood have been considered incorrupt. One of the most well-known books on the topic, "The Incorruptibles," by Joan Carroll Cruz, lists more than 100, beginning with St. Cecilia, an early Christian martyr. More recently, the body of Benedictine Sister Wilhelmina Lancaster, who was buried in 2019 in Missouri, appeared to not experience normal decomposition, according to medical experts who examined her remains.

"The Catholic Church does not have an official protocol for determining if a deceased person's body is incorrupt, and incorruptibility is not considered to be an indication of sainthood," the local bishop, Bishop James V. Johnston of Kansas City-St. Joseph, explained in response to the findings in 2024.

Many of the experts who spoke with OSV News also made clear that an incorrupt body does not prove someone is a saint. Others recognized that many saints who are considered incorrupt appear only partially incorrupt or have body parts that are incorrupt. Some saints, they added, seem to be incorrupt only temporarily.

"When I encounter a case of reported incorruptibility, my scientific mind immediately runs through the variables: Was the body embalmed? Was it in a naturally preservative environment, like a bog or a dry, cold climate?" Dr. C. Gustavo De Moraes, associate professor of ophthalmology at the Columbia University Medical Center and attending physician at New York Presbyterian Hospital, said in emailed comments. "These are the essential first questions."

He emphasized the importance of what "incorrupt" means in this context.

"It does not necessarily mean being perfectly preserved as a living human being," he said. "It means the body did not decay as one would expect based on the conditions of the burial, the cause of death, and the length of time since death."

Is incorruptibility a miracle?

At the University of Dayton, Carter said the term "incorruptible" is "usually used to mean a presumed miracle, some sort of divine intervention to show God's favor for a particular holy person."

"I think it's really only in the Catholic and Orthodox religious cultures that one sees the sign of incorruptibility as something miraculous, something from God," he added.

If incorruptibility is a miracle, it likely falls under what St. Thomas Aquinas describes as a "qualitative miracle," Donald J. Bungum, associate professor of philosophy and of Catholic studies at the University of Mary in Bismarck, North Dakota, said.

"A qualitative miracle is a case in which God does what nature has power to do, but he does it beyond nature's manner of acting or without the working of natural causes," he said.

"Nature can preserve dead organic matter from decomposition, but nature cannot do so without environmental or artificial means of preservation," he said. "But this is exactly what seems to be the case for the bodies of some saints."

What is the significance of incorruptibility in the church?

At Providence College in Rhode Island, Paul Gondreau, a professor of theology, said that incorruptibility "expresses how essential the body is to our human identity."

"What role does the body play in our human identity, in our moral agency? Is there a moral duty that we have with respect to our body?" he said. "All this hinges upon whether to be human is to be an embodied thing -- and this is what I think the incorruptibles confirm, first and foremost."

Gondreau, who has seen the bodies of incorrupt saints, including St. Bernadette Soubirous, said incorruptibility signifies a miracle. For Catholics, incorrupt bodies also witness to "the reality of the resurrection of the body."

"The fact that it's not something suffering corruption, or at least total corruption, is itself miraculous and thus points in its own small, partial, but nonetheless significant way to the fact that the bodies are awaiting the resurrection," he said of incorruptibles.

What is the church's history with incorruptibility?

The church takes a more open approach to incorruptibility, according to Carter.

"As with approved Marian apparitions, the church is very cautious in certifying apparent miracles, leaving much of this up to the pious sense of individual faithful, so it remains outside the rules and procedures of the official canonization process overseen by Rome," Carter said of the significance of incorruptibles in the church.

Carter, who is on the canonization cause for Servant of God Father Vincent Capodanno, said he is not aware of an instance where incorruptibility was counted as a miracle for someone's cause to sainthood in many centuries.

"I think even in the very distant past, that was not common," he said. "It's certainly not the case now, and the church does not currently accept incorruptibility or the appearance of it as a miracle for a canonization."

He addressed the historical significance of incorruptibility in a follow-up email.

"Historically, within Christian theology, corruption and decay were associated with sin and death ... therefore, incorruptibility was a sign of holiness, of innocence and purity, and an incorrupt body could be interpreted as a manifestation of divine intervention ... a heavenly sign of divine approval of a person's life and endorsement of their sainthood," he wrote.

How do scientists approach incorruptibility?

Several members of the Society of Catholic Scientists also spoke with OSV News about how they approach incorruptibility from their particular backgrounds. Elizabeth Komives, distinguished professor of chemistry and biochemistry at University of California San Diego, called incorruptibility a miracle and distinguished it from the natural biological processes that occur after death.

When a body stops breathing, "all the metabolism within the body shifts from what we call aerobic metabolism -- which requires oxygen and that's why we breathe -- to anaerobic metabolism," Komives said. "That then begins a process where the body becomes more acidic and enzymes get activated that break the body down."

These enzymes, called proteases, digest the body from the inside out, she said. Bacteria also play a role. Komives said that, in the human body, there are 10 times as many bacteria as there are human cells.

"When a person dies, when they stop breathing, eventually what you see is the body bloats," she said, due to gas produced by bacteria.

"There are scientific explanations for incorruptible bodies and incorruptible saints," Stephen J. Mattingly, retired professor of microbiology and immunology at University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, said in emailed comments.

"They may differ depending on a variety of factors, such as pH of the tissues, whether or not water is available for microbial growth and degradation, the production of antimicrobial factors by certain bacteria along with specific requirements for the activity of enzymes involved in the breakdown of human tissues," he said.

Iker Antón Ibáñez, who teaches the postmortem examinations (necropsy) module in the pathological anatomy and cytodiagnosis program for medical laboratory technicians at Arangoya Educational Center in Bilbao, Spain, also listed relevant factors.

"I explain to my students that after death, the human body undergoes a series of immediate, intermediate, and late postmortem signs -- from the cessation of vital functions and lividity to decomposition and eventual disintegration," Ibáñez said in emailed comments. "Under certain conditions, however, this natural process can slow or even stop, producing phenomena of preservation such as mummification, corification, or adipocere formation (saponification)."

He added: "These are well-known in forensic medicine and often clarify cases that might otherwise seem extraordinary."

Ibáñez also noted that many incorrupt saints came before the development of modern forensic science.

"In some cases, embalming, entombment in sealed or low-humidity urns, or even partial silicone reconstructions were later performed to preserve or restore the body for public veneration -- practices that can mask normal postmortem changes," he said.

Incorruptibility, he said, "provides an opportunity for respectful dialogue between science and faith -- one that values both empirical evidence and spiritual interpretation."

What is the relationship with science and faith here?

Many of these experts agreed that science informs faith with respect to incorruptibility.

"I would argue that science is what makes faith in this particular miracle possible and rational," Columbia's De Moraes said. "Without our modern scientific understanding of microbiology, biochemistry, and decomposition, the phenomenon of incorruptibility would be far less meaningful."

Instead of debunking the miracle, science illuminates it, he said.

"If we didn't know that bodies are supposed to decay, an incorrupt saint would just be a curiosity," he said. "But because we know precisely how and why they should corrupt, their preservation becomes a powerful sign."