There can be no better patron for a time of crisis than St. Joseph of Nazareth.

He lived in a moment of crisis — political, cultural, moral, and religious — and he raised a family in such a moment.

He faced personal crises as well. In fact, every episode we know with certainty from his life was a moment of extreme duress. He faced an unplanned, out-of-wedlock pregnancy. He undertook a long journey with his pregnant wife when he knew her due date was imminent.

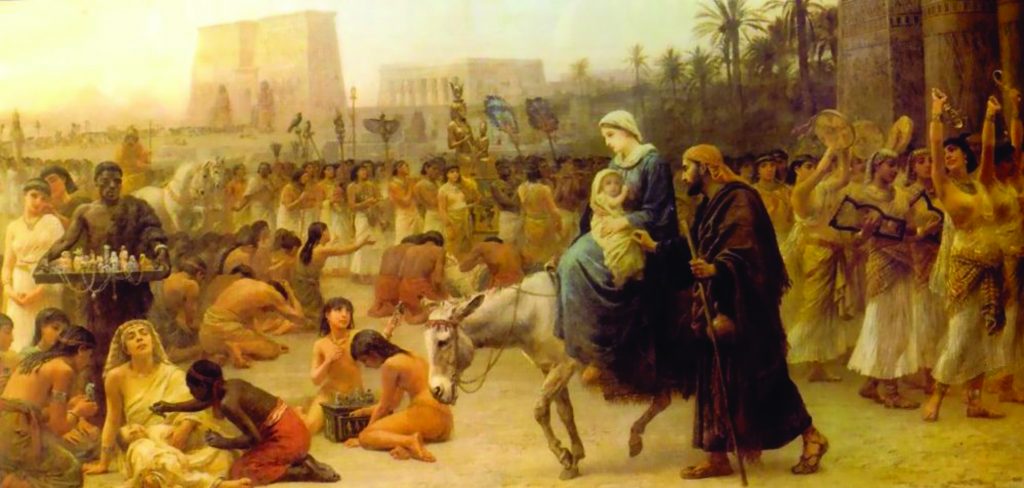

He had to flee with his family — for months and for more than a thousand miles — to escape the wrath of the most powerful man in his world. The last time we see St. Joseph, he is confronting the horrible possibility of child loss, when his child went missing in the teeming metropolis of Jerusalem.

Times of crisis require decisions. For St. Joseph, some were immediate, but fraught with potential consequences. Should he turn westward, toward the coast, right now? Or should he wait till the next junction of roads?

Other dilemmas involved the long-term flourishing of his wife and child. Should the family flee to Babylon, where they probably had many kin, or to Egypt?

Every choice St. Joseph faced was urgent, and yet he made them all well. He made use of all the resources available to him. He thought. He prayed. He acted. We never see him complaining or lamenting, though he would have been justified in doing both. In fact, we never see St. Joseph speaking at all, and we never see any human being speak to St. Joseph.

We all know the ending of the story. St. Joseph guided his family through the direst perils. He supported his household amid the most challenging economic circumstances. He raised history’s most virtuous son. Thus, St. Joseph’s own decisions served as a precondition of the world’s salvation.

Pope Francis has declared 2021 to be a special Year of St. Joseph, and Christians would do well to live it intentionally, to cultivate the habits best suited for life in a moment of crisis.

Much of St. Joseph’s life coincided with the reign of one king: Herod the Great. Herod occupied the throne in Judea from approximately 36 B.C. till 1 B.C., and many observers judged these to be years of relative peace and prosperity in the Holy Land.

Building upon the triumphs of his predecessors, the Hasmoneans, Herod expanded the territory of his kingdom and asserted Jewish identity. At the same time, he maintained excellent relations with Rome, which was the emerging world power at the time. Judea was a crossroads, valuable to the Romans for commercial and military movement.

Herod was a master of diplomacy. He showed the world his skill in negotiations with the major players on the world scene, like Cleopatra, Marc Antony, Caesar Augustus, and Cassius.

He undertook a building program that was unprecedented in antiquity, building cities where mere villages had stood before and enormous public works, including aqueducts, fortresses, reservoirs, and a man-made harbor at the seaport. He built grand complexes for entertainment and shopping.

He rebuilt the Temple in Jerusalem and made it even grander than Solomon’s original. Still today, Herod holds several world records for his architectural marvels: largest palace ever built, largest plaza, and largest royal portico.

All of this was good for the economy. Manual laborers — men like St. Joseph and his extended family — experienced the reign of Herod as a time of boundless opportunity. Perhaps for the first time in history, carpenters could grow wealthy from their craft.

Even in his lifetime Herod was known as “the Great,” and it’s easy to see why.

His secret to a long rule was to keep his people awestruck. And he accomplished this by two means: monumental building — and massacres.

He was a brutal despot, jealous of his power and suspicious of any potential rivals or rebels. Over the years, he arranged the murder of three of his sons, one brother-in-law, his mother-in-law, and the most beloved of his 10 wives.

Once, in response to an act of vandalism, he had two rabbis burned alive; and then he commanded that all their disciples be found and killed. On another particularly bad day, he ordered the massacre of 300 of his military leaders.

According to still another account, he had all but one member of the Jerusalem council put to death when they declined to proclaim him as the long-awaited Messiah. Then Herod blinded the only surviving councilor, so that the man could serve as a living warning to others who might wish to challenge the royal vanity. Even on his deathbed the king was busy plotting his next mass killing.

Herod was vain. He was paranoid. And his fearful subjects held him in contempt. But they kept such thoughts to themselves, because they knew his spies and informants were everywhere.

Thus, Judea’s age of prosperity was an age of constant anxiety. Herod created jobs, raised wages, and lowered taxes. He made treaties and opened trade with lands near and far. Yet he was universally despised, and he knew it.

To survive in such times — and survive with one’s integrity — required the virtue of prudence in a heroic degree. No saint in history showed himself to be more prudent than St. Joseph of Nazareth.

Prudence is a virtue much misunderstood. In movies and television shows it is often invoked as an excuse for cowardice and inaction, a cloak for endless delay while all sides of a question are examined microscopically.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

Prudence is, in fact, a mental habit that is always oriented to action. The Catechism of the Catholic Church defines it as “the virtue that disposes practical reason to discern our true good in every circumstance and to choose the right means of achieving it.” St. Thomas Aquinas said that prudence is “right reason in action.”

In the stories in the Gospel we see St. Joseph as a man of action. We have none of his words, so we know him only through his deeds.

Yet we never see him act rashly or impulsively. Surely he had human passions, and he suffered their effects intensely. He lived in a time of crises, many of which affected him directly. But he never allowed those extreme stressors to overwhelm his rational thought. He examined matters thoroughly, and then he “resolved” to act.

He did all this, moreover, in the context of habitual prayer and a deep knowledge of Scripture, and those were the key elements in all his decisions. They provided the context that was necessary for prudent action.

St. Joseph’s personal history was bound closely with his nation’s history. The opening verses of the New Testament make this clear as they introduce his name at the end of a genealogy that begins with the patriarch Abraham. St. Joseph grew up hearing the stories from Scripture about his ancestors’ repeated successes against extraordinary opposition.

He heard also of their failures, followed by God’s deliverance. He knew, too, of the promise of a Messiah, who would deliver the people of Israel, some 490 years (70 weeks of years) after the oracles of the prophet Daniel.

It is in the context of this history that St. Joseph came to understand his own identity. And it is in that same context that we encounter St. Joseph.

The long genealogy in St. Matthew’s Gospel drops us into the middle of a drama. Without a word of introduction about the character of Mary or St. Joseph, the story begins: “When … Mary had been betrothed to Joseph, before they came together she was found to be with child of the Holy Spirit” (Matthew 1:18). The verses that follow tell us that St. Joseph “considered” the matter and, upon consideration, he “resolved to divorce her quietly” (vv. 19–20).

So, from our first glimpse, we see him in thought that is oriented to action. We see him as a prudent man.

He is firmly resolved, and yet there is nothing fanatical or inflexible about him. He is, in fact, willing to change his mind when presented with authoritative facts. It is an angel, then, who does just that: he reveals God’s plan for the child, and St. Joseph immediately changes his intention. He proceeds immediately to action, but a different course of action. He “woke from sleep” and “did as the angel of the Lord commanded him” (Matthew 1:24).

In all that transpired, we learn nothing about St. Joseph’s feelings, which must have been tumultuous. What we see instead are his thought, prayer (with the angel), and action. We see his prudence.

It is a virtue he certainly had to exercise daily. He was a craftsman, a carpenter, and so he worked at a trade that was highly valued by the king. That could be a good thing; it could be financially lucrative. But with a king like Herod it could be disastrous as well.

What if Herod should take a sudden interest in descendants of King David? They could, after all, easily become rivals for the throne. What if Herod should take interest in residents of Nazareth, a village known (and named) for its expectation of the Messiah? If informants at one of St. Joseph’s worksites wanted to cast suspicion on the man, it would be very easy to do.

St. Joseph kept to his work. There were many political movements active in the carpenter’s lifetime, but we have no evidence that they interested him. Some promoted active resistance to Herod. Others urged noncooperation with Rome.

Yet we find in the Gospel that St. Joseph recognized both Herod and the Romans as legitimate authorities. Though he certainly knew Herod to be mad and the Romans to be idolatrous, he submitted to their rule. We see this clearly in the story of his journey to Bethlehem with Mary.

They made the trip because the Romans required everyone to register for taxation. Now, St. Joseph had good reasons to ignore the summons. His wife was nine months pregnant, and the 90-mile trip would have required several days of travel by foot or on the back of a donkey. He could have claimed hardship.

He knew, moreover, that some of his taxes would be used to build shrines and temples to the false gods of Rome. He could have resisted on religious grounds.

But he complied. He considered the matter. He prayed. Then he set off for Bethlehem.

In time, however, the same virtue would lead him to flee the king’s order that directly threatened the life of his child. Instead, he fled with his family to Egypt — a refuge he chose over other options, because a pious Jew could raise a family there in the diaspora community.

In the small details of the brief story of St. Joseph, we find clear guidance for living in times of crisis, when sometimes we must engage and sometimes withdraw. May we learn from him, exercising prudence that’s informed by consideration, prayer, and Scripture.