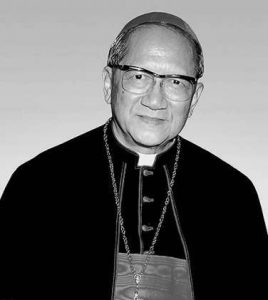

At the International Eucharistic Congress of 2000 in Rome, I had the opportunity to hear a beautiful witness by Cardinal Francis Xavier Nguyen Van Thuan of Vietnam, and later greet him personally.

His story is very moving. He had been named archbishop coadjutor of Saigon shortly before that city fell to the Communist forces of North Vietnam. He became a prisoner and eventually was held in solitary confinement for nine years.

His witness was about the Masses he celebrated alone in his cell. He had written some of his friends, asking them in coded language for altar wine. He saved crumbs of bread, and with a few drops of wine in his hand he celebrated the Eucharist. His lectionary was in his mind, his sacramentary the memorized words of consecration, his paten and chalice his own hand. His church was the prison cell and his ministry, cut off and isolated as it was, worked for the sanctification of his faithful flock. He was alone but not alone.

The story of his secret Eucharists resembles that of other priests who suffered in totalitarian regimes. Father Walter Ciszek, SJ, a priest from Pittsburgh who had been sent to the Soviet Union as a missionary, had a similar experience. When he and some other priests were prisoners in a labor camp, they feared that they would not be able to continue having Mass.

“We began then to do what we probably should have done before: We began to prepare ourselves to say the Mass by heart,” wrote Father Ciszek in his book “He Leadeth Me: An Extraordinary Testament of Faith.”

“We were afraid we would lose our Mass kit, the chalice or the missal; but we were determined that as long as we had bread and wine we would try to say Mass somehow.”

The priests memorized the Mass prayers, repeating them to themselves over and over again until they had it all by heart. Father Ciszek held this as a special grace for which he was thankful for the rest of his imprisonment and, really, his life. They lost the missal and the chalice and paten, but were able to celebrate the Eucharist from the heart.

I have been thinking of these heroic examples in the midst of the coronavirus (COVID-19) crisis that has deprived the faithful of the Eucharist in so many places and made the priest’s daily offering of Mass a kind of suffering.

The instruction the bishop gives to those to be ordained priests in the ritual of ordination states: “You must carry out your mission of sanctifying in the power of Christ. Your ministry will perfect the spiritual sacrifice of the faithful by uniting it to Christ’s sacrifice, the sacrifice which is offered sacramentally through your hands.”

When I was ordained, my pastor gave me a framed copy of a poem about “the hands of the priest” that reflected neither the vocabulary nor the theology of my seminary preparation. That preparation framed the sacrament in terms of our relationship with the community, but sometimes (and unfortunately) at the expense of the ontological character of our ordination.

We were to be “presiders” at the Eucharist, and that presidency seems mitigated and strange when there are no faithful present. For many priests of a certain age, saying Mass alone is an unwelcome experience.

This, I believe, is a hidden aspect of this crisis, which has some of the faithful angry at not being permitted access to the Eucharist: They don’t always understand that a priest also feels deeply the physical distancing of the community. It is, of course, only physical, because the Eucharist is the source and summit of Christian life and connects all of us together. But a shepherd isolated from his sheep suffers their absence.

After the priest is ordained, the bishop presents him with the paten and chalice and says, “Accept from the holy people of God the gifts to be offered to Him. Know what you are doing, and imitate the mystery you celebrate: model your life on the mystery of the Lord’s cross.”

A priest cannot hold a chalice or paten without some reference to that commission and that gift from the “holy people of God.” How lonely the Mass can become without the company of those for whose sanctification it is offered.

Personally, I am very concerned about how priests are taking the isolation of the quarantine. I fear that some will be very depressed and that the stress and anxiety they feel will not be understood and addressed. One priest joked to me, “It’s Holy Thursday; do they want me to wash my own feet?” The bitterness of the humor was a covering for a wound.

Priests are not used to praying the greatest and highest prayer alone. Our lives are often lonely enough.

I suppose that the only thing we can do is identify with the Christ who moved a stone’s throw away from his disciples at Gethsemane, sweating blood as he prayed, “Thy will be done.”

His aloneness was only emphasized when he discovered Peter, James, and John asleep. No one accompanied Jesus in the sham trial that night or during the mockery of the Roman soldiers. His isolation makes ours seem very small in comparison.

He was alone, of course, on his altar the cross, as many priests will be today at the altar in their churches. Jesus’ words from the cross invoking the psalm that begins with the feeling of forsakenness by God is a moving reminder of his loneliness and his aloneness. His loneliness, I say, because his humanity had to be overwhelmed by the sentiment of abandonment.

Obviously, he was not completely alone because Mary, John, and Mary Magdalene were at the foot of the cross, and because the divine community of the Trinity was not and can never be broken or interrupted. But the human heart of the Savior, “overwhelmed by insults,” as the Litany of the Sacred Heart prays, and “broken for our sins,” comprehended and embraced all the sufferings of all the hearts of the world.

We priests should think of our heroic brothers who have had to celebrate the Mass in conditions much worse than we. Father Ciszek and his brother Jesuits still kept the Eucharist fast from midnight and sometimes had to wait all day before they had a chance to say their secret Masses. Cardinal Nguyen could speak to no one before or after his Masses in solitary confinement. Their heroism invites us to focus on imitating the mystery we celebrate, as the ordination rite made clear to us.

A popular meditation during my time in the seminary was that of Father Teilhard de Chardin, SJ, a priest who was caught in the Gobi Desert without what he needed to say Mass and offered to God the whole material world of his horizon, the “Mass on the World.” He was also alone.

We priests have a much better opportunity. Alone with the One who was alone on the cross, we speak his words over the bread and wine and our voices and hands are his.

We can offer more than the rising sun: Christ’s body and blood for the salvation of the world. We can elevate with the host and the chalice the lives of all our people, their difficulties, their frustrations, their sorrows and their joys, and for a minute the quarantine will disappear as we are united in a cosmic and eternal communion, beyond all time and space, with the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

The Masses we offer from the pain of this crisis cannot help but move our Lord to bless us and preserve us in this grace now and always.

Author’s note: The following are extracts from the late Cardinal Francis Xavier Nguyen Van Thuan’s address, "Experiencing God's liberating power," given at the 2002 Los Angeles Religious Education Conference just prior to his death in 2002.

“ ‘Were you able to say Mass in prison?’ is a question I have been asked many, many times. And when I say ‘Yes,’ I can foretell the next question, ‘How did you get the bread and wine?’ ”

“I was taken to prison empty-handed. Later on, I was allowed to request the strict necessities like clothing, toothpaste, etc. I wrote home saying, ‘Send me some wine as medication for stomach pains.’ On the outside, the faithful understood what I meant.”

“They sent me a little bottle of Mass wine, with a label reading ‘medication for stomach pains,’ as well as some hosts broken into small pieces.”

“The police asked me: ‘Do you have pains in your stomach?’ ‘Yes.’ ‘Here is some medicine for you!’ ”

“I will never be able to express the joy that was mine: Each day, with three drops of wine, a drop of water in the palm of my hand, I celebrated my Mass.”