The U.S. bishops are encouraging Catholics to deepen their love for the Eucharist as part of the ongoing National Eucharistic Revival initiative. In light of that effort, the following is the fourth in a series from Angelus contributing editor Mike Aquilina on the meaning and makeup of the Eucharistic Prayers.

The eucharistic meaning of the holiday is built into its name. Christmas is an abbreviated form of “the Christ’s Mass.” But there’s much more to the connection than that.

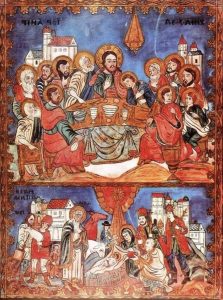

Established at the Last Supper, the sacrament was foreseen by God from the beginning of creation; and from the beginning of Jesus’ earthly life he was preparing the way for it.

God is the primary author of Scripture and also of history. So he told stories to set the stage for future stories. He arranged events to foreshadow future events. Jesus himself saw history this way. He observed that many particular details in the Old Testament prefigured his own life and work.

After reading an oracle of the Prophet Isaiah, he told his synagogue congregation, “Today this scripture has been fulfilled in your hearing” (Luke 4:21). And, when walking with two disciples on the day of his resurrection, “beginning with Moses and all the prophets, he interpreted to them in all the scriptures the things concerning himself” (Luke 24:27). The Old Testament spoke of Jesus centuries before he was incarnate.

In Jesus’ own lifetime we see the pattern continue. Events early in his ministry find fulfillment later in his earthly life. The multiplication of loaves (Luke 9:12-17) points to his Bread of Life discourse (John 6:26-66) and then to his self-offering in the bread of the Last Supper (Luke 22:19).

The very name of Jesus’ birthplace suggests his title as the Bread of Life. In Hebrew, Bethlehem means, literally, “House of Bread.”

Bethlehem was important because it was “the city of David,” the Lord’s royal ancestor. But the prophet Micah, in the eighth century before Christ, predicted a still greater destiny for the town — involving a divine king: “But you, O Bethlehem Ephrathah, who are little to be among the clans of Judah, from you shall come forth for me one who is to be ruler in Israel, whose origin is from of old, from ancient days” (Micah 5:2).

Bethlehem’s royal connection was important, because it confirmed Jesus’ status as “Son of David” and “King of Kings.”

But now — in Jesus the Bread of Life — the town was fulfilling its deepest identity.

It was in Bethlehem that the newborn was placed “in a manger,” a feeding trough filled with grain. And his family was resting among the animals because “there was no place for them in the inn” (Luke 2:7). The word translated as “inn” in Luke 2:7 is nothing so grand as a hotel or even a motel. “Kataluma” means literally an “upper room,” and it is translated that way later on in Luke’s Gospel when it denotes the place where Jesus instituted the Eucharist. It is as if the time for the upper room had not yet arrived; it would come with Jesus’ last Passover.

Nor do the correspondences end there.

Mary is honored in Christian tradition as the Ark of the Covenant. She is called by that name in the Bible’s final book (Revelation 11:19-12:1–2). The original Ark contained the relics of Israel’s Exodus, including a jar of manna, the miraculous bread sent from heaven to sustain the Chosen People during their sojourn in the desert (see Psalms 78:24–25; 105:40). But, in the fullness of time, Mary, the true Ark, contained the true “Bread from Heaven” (John 6:31–33) as she bore Jesus in her womb.

The subplots in the Christmas story exercised their own deep influence on future Christian liturgy.

From the angels of heaven the shepherds learned the song now known as the “Gloria” — “Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace to people of good will!” It has, according to reliable early sources, been used in the Mass since the second century.

The magi, for their part, bore three gifts — gold, frankincense, and myrrh — that the Church would later associate with the sacraments: gold for its chalice and other sacred vessels; incense in its thurible; and myrrh for anointing.

Some scholars, furthermore, believe that the shepherds near Bethlehem were tasked with supplying lambs for sacrifice in the Jerusalem Temple. If that is the case, then these were the “lambs of God” in which John the Baptist saw the image of the Messiah, God’s suffering servant (John 1:29, 36). And so today, at every Mass, the congregation addresses Jesus with the title, “Lamb of God, you take away the sins of the world, have mercy on us.”

This way of reading the Bible is called “typology,” and it was practiced by the Old Testament prophets as well as the New Testament apostles (and, of course, by Jesus). Earlier “types” anticipate later fulfillment.

The types find completion not just in the earthly ministry of Jesus, but in the sacraments of the Church. Noah’s flood “corresponds to” baptism (1 Peter 3:20–21). Medicinal anointing finds its fullest meaning in sacramental anointing of the sick (Mark 6:13; James 5:14).

As with these sacraments, so with the greatest of sacraments, the Blessed Sacrament, the holy Eucharist. It is anticipated in the biblical record from the very beginning.

It should come as no surprise, then, that the Church sees every Communion as a Christmas — the advent of the Savior — and every Christmas as a eucharistic feast.