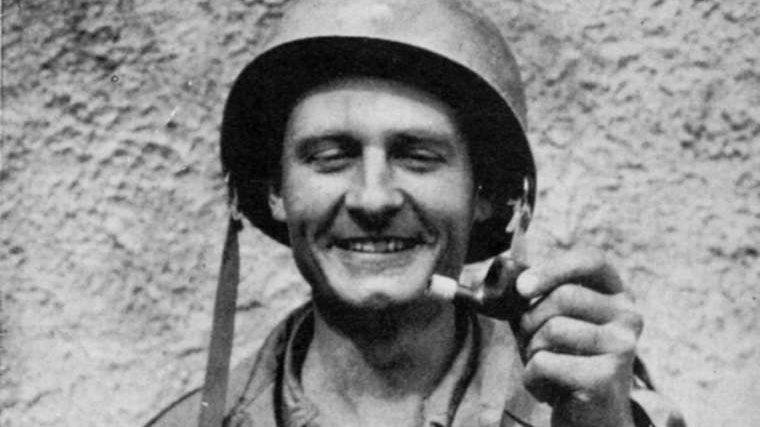

A Kansas priest recalls the holy deeds of Servant of God Emil Kapaun, a POW and chaplain during the Korean War, whose path to sainthood will meet a major milestone next month.

Bishops and cardinals from the Vatican’s Congregation for the Causes of Saints will vote March 10 to on whether the process to declare Kapaun a saint should progress to the next stage of advancement.

Kapaun was named in 1993 a “Servant of God,” the first designation on the way to being declared a saint. To be declared “venerable” is the second step in the canonization process, a step which Kapaun could reach next month.

Father John Hotze, the postulator for Kapaun’s cause, said the priest, whom he described as an average man from Kansas, is an example of stewardship and selflessness.

If Kapaun does become a saint, “then there's hope for each and every one of us to be a saint, also,” Hotze said.

“He was just an average guy. He was just a poor Kansas farm boy. He had nothing, and he was able to use what little he had in service to others,” he said.

“He used all of his time and talent and treasure in service to God and in service to others.”

Kapaun, who was born during the Great Depression in Pilsen, Kansas; was ordained a priest in 1940 and began ministry as a parish priest in his hometown.

During World War II Kapaun would offer the sacraments at the nearby Harrington Army Air Field until he became a full-time army chaplain in 1944. He was stationed in India and Burma for the duration of the war. There, he offered soldiers the sacraments, and, Hotz said, served his unit with a selfless attitude.

“I was speaking to his brother Eugene once, and his brother said that he thought [Emil] always had that missionary spirit in his heart.”

“He said that he thought one of the reasons why [Emil] asked to become a chaplain was because he knew that that would be part of this missionary life,” he said.

Hotze described Kapaun as a “soldier’s chaplain” who would do anything for his men.

Because the priest’s jeep had been damaged, Kapaun would often ride his bicycle, meeting men even at battlefield front lines, and following the sound of gunshots to find out if he was

“[The soldiers] would all look up to see where Father Kapaun was at because, they said, as soon as they heard the gunfire, … they knew that he would be on his bicycle … [Kapaun] knew that's where he would be needed,” he said.

After World War II ended, Kapaun used his GI bill to study history and education at the Catholic University of America. He returned home as pastor of his boyhood parish briefly and served at a few other parishes until the army had need of him.

In 1948, the United States issued a call for military chaplains to return to service. Kapaun jumped at the chance. He was then sent to Texas, Washington, and Japan, before being deployed to Korea.

Hotze said that many of the men serving in the same unit viewed him as a saint. He said Tibor Rubun, a Jewish soldier, was once worried during an attack when Kapaun comforted him and began praying with him using the Hebrew Scriptures.

During the Battle of Unsan in November of 1950, Kapaun worked tirelessly to comfort the suffering and retrieve the wounded from the battlefield. One of the soldiers he retrieved was a wounded Chinese soldier, who helped him negotiate a surrender after he was surrounded by enemy troops. Kapaun was taken as a prisoner of war.

Hotze said Kapaun also saved Herbert Miller’s life, a man who had been shot and then wounded by a grenade, which broke his ankle and shredded his legs with shrapnel. Korean soldiers would kill any U.S. prisoners who could not walk to the camp, so Kapaun carried Miller 30 miles on a prisoners’ march.

Kapaun was then taken to prison camp number five in Pyoktong, a bombed-out village used as a detainment center. The soldiers at the camp were severely mistreated, facing malnourishment, dysentery, and a lack of warm clothing to counter an extremely cold winter. Kapaun would do all he could for the soldiers, washing their soiled clothes, retrieving fresh water, and attending to their wounds

When he developed pneumonia and a blood clot in his leg, the chaplain was denied medical treatment. He died in 1951.

“[He was] taken away to the hospital. The men called it the death house because you didn't come out of it alive. When they took you there, they didn't give you any water or they didn't give you any food or anything,” Hotze said.

“He wound up dying there and...the men talked about how there was not a dry eye in the camp.”

For his bravery at Unsan, Kapaun was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor by President Obama in 2013. The medal is the United States’ highest military award for bravery.

Hotze said Catholics today are still influenced and inspired by Kapaun. He said every June pilgrims march from Wichita to Kapaun’s hometown of Pilsen. They make the 60 mile walk in commemoration of the priest and his march to the prison camps. The pilgrimage last summer gathered about 200 people.

Hotze emphasized two aspects of Kapaun’s spirituality. He said Kapaun dedicated himself to the service of others and he did so joyfully.

“I think his willingness to serve is probably one of the most appealing things, and, another thing was that this willingness to serve, that he did it with joy.”

“He had every right ... to resent the situation that he was in, in his life or the difficulties that he was facing but he never did. He never was angry. He was never resentful or hateful.”