Scott Hahn is arguably the most widely influential Catholic layman of the last half-century. An ordained Presbyterian minister, he entered full communion with the Catholic Church in 1986 and pursued an academic career.

Since 1990 he has taught at Franciscan University of Steubenville. By the mid-1990s, his audio and video audience had reached millions. He is the author or co-author of dozens of books and has hosted or co-hosted dozens of television series. He spoke to Angelus about the third of the “Four Last Things”: hell.

How would you respond to the charge that belief in hell is not truly traditional?

Not long ago, people complained that the Church made it seem impossible to get into heaven. The two saints quoted most often in the Catechism, St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas, expressed no doubt about the existence of hell. In fact, they worried that most people might be going there. These are men renowned for their charity. I don’t think they were sadistically wishing the worst upon their enemies.

The truth is that almost all of our authorities — ancient, medieval, and modern — Scripture, tradition, and magisterium — agree on this point. There are very few exceptions. The two cited most often are Origen and St. Gregory of Nyssa, who considered himself a follower of Origen. Origen himself has never been canonized, and in fact some of his teachings were condemned by councils.

I think it’s folly to silence the Fathers, saints, doctors, mystics, and seers, all for the sake of a postmodern attempt to change part of the ending of the Christian story. Some people today seem to be making hell as hard to enter as heaven once was.

Hell, it seems, is under attack, at least as a Christian doctrine. Even The New York Times recently published an essay inveighing against traditional beliefs about damnation. Does hell even exist?

Well, we should all take that up with Jesus, since he told us 80% of what we know about hell. Taken together, they describe a state that is permanent and painful. And it’s not as if his statements are vague or ambiguous.

Consider the one I find most chilling: “Woe to that man by whom the Son of man is betrayed! It would have been better for that man if he had not been born” (Matthew 26:24; Mark 14:21). What Jesus said about Judas would be unthinkable for one person to say about another, if there were no hell. “Better not to have been born”? There’s no way to make sense of that if Judas got to enjoy the beatific vision.

Why would a merciful and good God create hell?

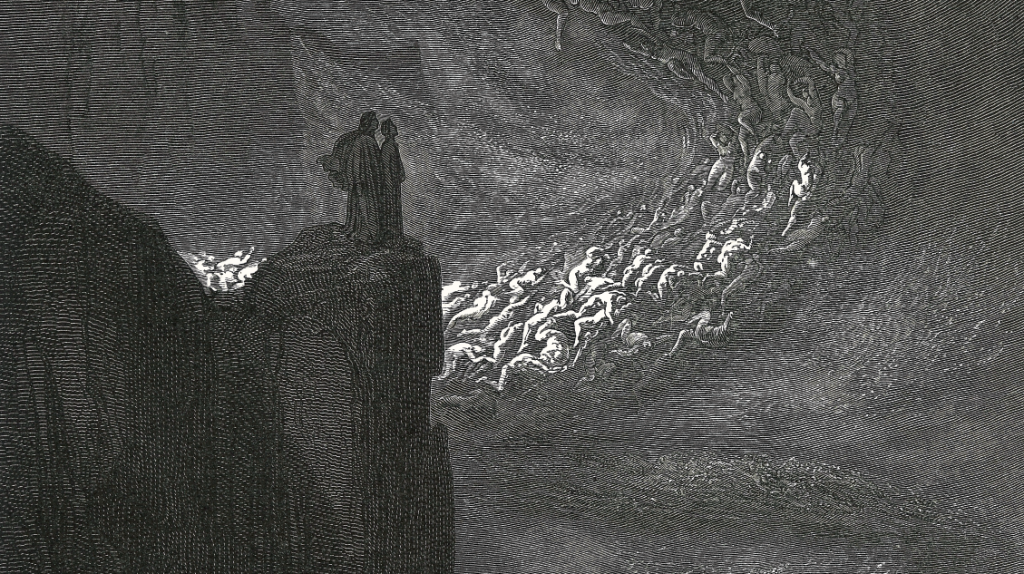

Step away from the traditional imagery for a minute. Concerning the “Last Things,” Scripture says, “What no eye has seen, nor ear heard, nor the heart of man conceived, what God has prepared for those who love him” (1 Corinthians 2:9).

What we have in the Bible then are terms that strain the limits of language. Hell’s endless fire and deathless worm are metaphors, just like heaven’s white robes and harps. But they’re extremely significant metaphors, because they tell us all we can know, given our current limitations.

Emily Dickinson was on to something when she said the parting is all we need to know about hell. Hell is a permanent parting from God. It’s the permanent choice for something other than God. That should be, for a Christian, the worst thing imaginable — worse than a fire that burns you or a worm that eats at you.

It’s a natural thing for a human being to crave love. It’s part of being human. To have that craving and yet repel its satisfaction would be hellish.

So you’re saying that hell is a choice?

It’s more than that. It’s the proof of our freedom to choose. It’s the guarantor of our freedom, because love cannot be compelled or coerced. God wants our love, but he will not force us to love him.

I think it’s fearfully possible to refuse God’s love. We see such refusals all too often, and sometimes they’re sustained over the course of a long lifetime. People make themselves miserable by their choices, but they dig in. They take their stand and plant their flag. Popular culture even celebrates that kind of rebellion. My friend Peter Kreeft once joked that the national anthem of hell is “I Did It My Way.”

St. Catherine of Siena said that a drop of contrition could empty hell. But there is no such drop. The souls in hell despise their lot, but they’d despise heaven more. God’s love would be hellish for those who do not want it. It would burn them more than hell does.

So where does the denial of hell come from?

I understand the desire to disbelieve in it. And I understand why there are so few people in the Church standing up for it. Who wants to be known as hell’s great defender? But, again, the big problem here is Jesus.

Is he the only problem?

No! There are many others. I already mention that to deny hell is to negate our freedom. Freedom is illusory if it will be trumped by a supposed mercy that negates deliberate rebellion against God and his grace.

But it also negates God’s justice. I’m not saying that God needs to extract his vengeful payback, his proverbial pound of flesh. I’m saying that the objectivity of the moral order is itself erased if sin has no real consequences.

Think of what sin visits upon the world. It’s not just broken laws; it’s broken lives, broken homes, broken relationships. It would be a false justice that merely accepted the wrongs in the same way as the rights. It would make God at once a relativist and a dictator, and his heaven a dictatorship of relativism.

So what is hell?

It’s a train that jumped the tracks to exercise its freedom. It’s a fish that jumped the bowl to be free of the water. Hell is where you go to unite self-assertion and self-deception with its original source. On this side of death we can experience the consequences of sin in a remedial way. We can let them purify us and restore us. I’ll bet that many of the wisest and holiest people you know are the people who have suffered the most.

The consequences of sin can be an occasion of healing. You’ll learn that if you attend an AA meeting. People hit bottom, and some of them recognize that they need to climb up and out. But they need to make that decision.

We can refuse to be healed, and we can refuse this repeatedly, obstinately, and even permanently, at the hour of our death. It’s a surplus of pride, not a lack of mercy, that keeps humans from obtaining heavenly glory.

But, again, it’s our choice. It’s because we have sinned against the light that we become willfully darkened.

Some of those who deny hell say that God will annihilate the damned, so that they won’t suffer. But it will rather be as if they had never existed.

That’s interesting, but there’s no support for it in Scripture or tradition. It’s a hypothesis of fairly recent vintage. Remember it’s God’s wisdom and power and goodness that have formed creatures, whether angels or humans or rocks. He loves all that he has created. We can’t stop him from loving us. But neither can we stop him from loving us in the way that he loves. He will not annihilate us or bring about our nonexistence. We will be the creatures he made us to be, but unfulfilled, incomplete, and miserable.

How should belief in hell affect our day-to-day lives?

Fear of hell is the lower part of contrition. It’s better for us to be motivated by pure love. But it’s OK if we’re motivated by pure fear! It’s a start. Even Scripture tells us to work out our salvation in fear and trembling.

In the traditional act of contrition, we say that we’re sorry because we “dread the loss of heaven and the pains of hell.” That’s the beginning of conversion.

Eventually, what we want is a right ordering of loves and a right ordering of fears. We want to love God more than any created thing we’ve formerly preferred through sin. We want to fear the loss of God more than the pains of hell.

What we don’t want is to be like the damned, who, according to Jesus, just wail and gnash their teeth. They don’t repent. They recognize their failure, but they’re still too proud to do anything about it.