In the lead-up to Christmas, Angelus has been looking at three Old Testament prophets who anticipated the story of Christ’s birth. The following is Part Three of our three-part series. Read Part One here, and Part Two here.

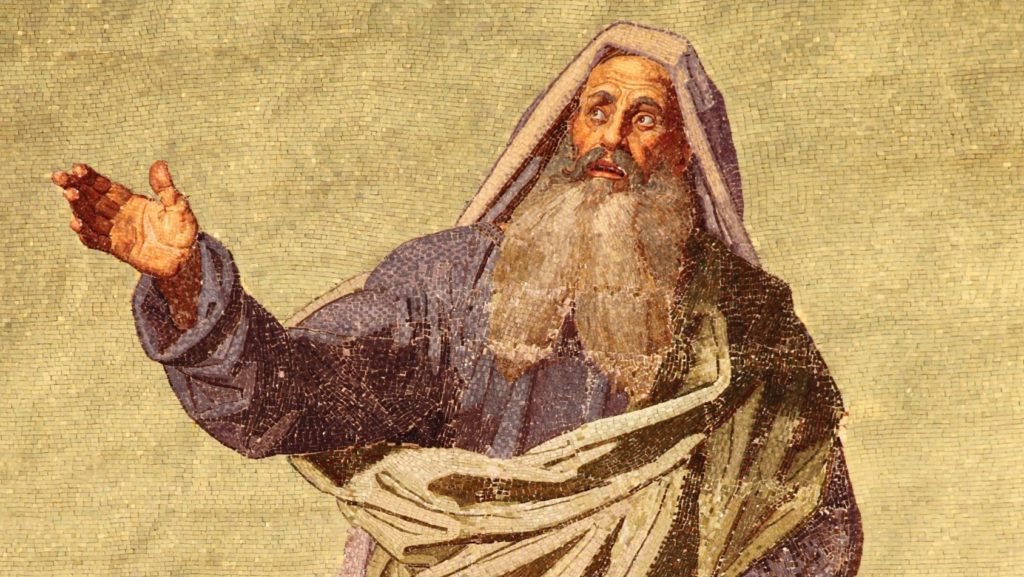

The prophet Daniel is not usually the first Old Testament figure people think of during Christmas.

The Church’s hymns and prayers spotlight Isaiah, who foretold the virginal conception of the Messiah (Isaiah 7:14). They speak of Micah, who pinpointed the location of his birth (Micah 5:2).

Yet the Book of Daniel powerfully shaped the Church’s imagination for both Advent and Christmas. In fact, though Daniel had lived and died hundreds of years before Christ, it was he who roused expectation, during the reign of King Herod the Great, that the time of the Messiah had arrived.

Daniel lived in a time of crisis for God’s chosen people. In 605 B.C., the armies of Babylon, led by King Nebuchadnezzar II, laid siege to Jerusalem and then took it captive. They returned home with treasures from the kingdom of Judah and from its Temple. They also seized as captives the best and brightest men of the young generation, and among them was Daniel.

He was among the first of the Jews to be taken into exile, and in Babylon he served the king with loyalty and skill. Daniel proved himself in virtue and earned the respect of his captors. He also received supernatural gifts from God. He had the ability to interpret dreams. He saw visions of future events. His prayers were efficacious.

On behalf of his people, Daniel sought answers from God. In prayer he learned that Jerusalem would be desolate for 70 years, and he sought to make reparation for the sins of his fellow Jews. An angel told him, however, that the holy city would not be fully restored for “seventy weeks of years” (Daniel 9:24) — that is, seventy times seven years. From the time of the exile until the restoration and rebuilding, 490 years would pass, and then would come “an anointed one, a prince” (9:25). In Hebrew the word for anointed is Mashiach (Messiah); in Greek it is Christos.

What else did Daniel say about the Christ? He would be “one like a Son of Man” coming on the clouds, receiving dominion and kingship from the Ancient of Days (7:13-14). Not merely earthly, he would exercise divine authority. His kingdom would be eternal — “not made by human hands” (2:34–35). It would encompass the whole world and destroy its idols.

The oracles of Daniel were preserved in the Book of Daniel, which was revered among the sacred books of the Jews. It brought a measure of hope and peace. The exile was a just punishment for the sins of Judah, but it would not be everlasting or indefinite. Daniel’s prophecy created a chronological expectation. There would be a measurable period between the captivity and the appearance of the Messiah.

So, for almost half a millennium, the people counted down the years.

The prophecy helps to explain why the reign of King Herod the Great was marked by expectation of the Messiah’s arrival. Those were the last years we recognize as “B.C.” — before Christ. By the time of Jesus’ birth, many Jews believed the prophetic clock had almost run down.

This helps explain why the Magi were alert to a royal birth (Matthew 2:1–2) and why “all Jerusalem” was agitated by news of a newborn king (Matthew 2:3).

It also explains why messianic movements were erupting throughout Judea. The Jewish historian Josephus mentions several figures who claimed to be the Messiah in the years just before Jesus’ birth. There was Athronges the Shepherd and Simon of Peraea; and there was Judas of Galilee, mentioned in Acts 5:37, who led a revolt around the time of Jesus’ birth and was later joined by his son Menachem.

The birth of Jesus occurred in this atmosphere created by Daniel’s timeline. Jesus was born in a moment when Israel knew the prophetic timetable was nearly up.

Hope ran high because Daniel’s promises for the Messiah’s reign were extravagant. He said the 70 weeks would end with God “finishing transgression,” “putting an end to sin,” and “bringing everlasting righteousness” (Daniel 9:24).

Advent’s great desire — “O come, O come, Emmanuel, and ransom captive Israel” — draws directly from this vision. And Christmas answers it: the Child is born to destroy sin and restore righteousness.

The early Christians saw the “weeks of years” as fulfilled in Jesus. The prophetic timetable became part of the early Church’s argument that Jesus’ coming was not accidental or random but divinely scheduled.

St. Irenaeus of Lyon highlights it in the second century, as do St. Hippolytus in Rome and Origen in Egypt in the third century. In the fourth century the witnesses are too numerous to mention, and they are geographically dispersed throughout the Christian world.

The message is universal, and it bears Good News: There is an end to all current sorrows, and that ending is the Christ. God arranged for human fulfillment to appear, and it arrived precisely on time.

Now redemption awaits only the love and consent of those who would be redeemed.