When I read an interview of a comedian who joked that all his unread books should be buried with him in his casket, I was both amused and pained. I have many books on my shelves that I keep as IOUs of my continuing education and which I have not opened or finished.

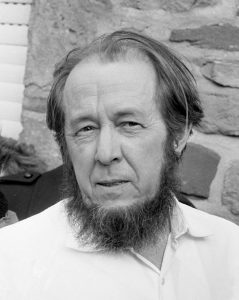

In college seminary, I bought every book by Alexandr Solzhenitsyn that I could get my hands on. I managed to read “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich” (in which the prisoner Shukhov, inhumanly reduced to the most basic of experience, is thankful for an extra bowl of mush that makes his day “almost happy”), “Cancer Ward” (a monumental Russian novel comparing the Soviet Union and cancer), “The First Circle” (a title taken from Dante’s “Inferno” about the elite prisoners of the Gulag) and one of his books of memoirs, “The Oak and the Calf.”

My goal of reading all three volumes of “The Gulag Archipelago” has taken me longer to achieve. The Gulag, with its almost 2,000 pages, is an intellectual Everest that requires some effort to read. This is despite the fact that I recognize that the work is not only a monument to resistance to Soviet Communism, unique in its genre of a secret history by eyewitnesses and outstanding in its impact on Western Civilization, but also is an Ali Baba’s treasure trove of portraits, stories, and insights.

Take two of the stories that Solzhenitsyn recounts about prisoners attempting escape from the concentration camps. Grigory Kudla, a Ukrainian, and Ivan Dushechkin, a Byelorussian, were working in a mine. Escaping through an air shaft, they walk for days without water. Dushechkin gives up. He tells Kudla, “I can’t go on anyway. Cut my throat and drink my blood.” He wanted the other to survive. Kudla was horrified, but was dying of thirst. He decided to walk on a little farther, all while taking the offer seriously.

The eucharistic implications of this story are obvious. A man was saying to his friend, “Drink my blood so that you can survive.” This should clearly make us think of Jesus’ words in the Gospel “Unless you eat my flesh and drink my blood you will not have life within you” (John 6:53). Jesus also said, “Greater love than this has no man to lay down his life for his friends” (John 15:13). Ivan wanted his death to conserve his companion’s life. His motivation was as moving as his plan was appalling.

But Kudla found water, “just as in the most improbable of novels,” and when he brought a container to his friend he had to convince him, “Yes, water.” They both crawled back to the spring and drank for hours. The terrifying choice that had been presented to him of letting his friend die in order that he might live was spared from him. If he survived, which he did, he would not have to carry his friend’s death around with him for the rest of his life.

The other story did not have as happy of an ending: Three men escaped from the gulag and found themselves on the steppe without food or water. One man was a common criminal, Solzhenitsyn said, another had become one in the concentration camp, and the third was a Ukrainian named Prokopenko. Desperately marching across the steppe for four days without food or water, the two criminals lost hope. They said to Prokopenko, “We decided to finish you.” He thought they meant to separate and leave him to walk alone.

He showed a picture of his family, but to no avail. The men stabbed him to death; however, his blood curdled and they couldn’t drink it. Solzhenitsyn describes what he calls “another striking scene: two men bending over another on the steppe, wondering why he wouldn’t bleed.”

I also find eucharistic associations in the horrible features of this story. These men were trying to get life by sacrificing another’s life’s blood, but their extreme hunger and thirst cannot palliate the grotesqueness of their selfishness. They attempted an unworthy participation in the life of another. The failure of their plan illustrates the wrongness of their action. They had stained their souls with no gain. They ended up, says Solzhenitsyn, “eyeing each other like wolves.”

After their crime, the men discovered water nearby, to compound their guilt. They were soon captured, and their lives were so endangered by the anger of their fellow prisoners for what they had done that they were transferred to a different prison. Their unholy communion had consequences.

Why am I thinking about these stories now? St. Paul wrote about the bad effects of unworthy Communion when he told the Corinthians that those who eat the body of Christ without honoring it, eat and drink judgment on themselves (1 Corinthians 11:29). I wonder if there were some in the community who thought he was “weaponizing” the sacrament when he wrote that receiving the body of Christ unworthily was the reason that “many of you are weak and sick, and some have died” (1 Corinthians 11:30). He certainly would have gotten my attention if I were there in Corinth.

The Eucharist is the sacrament of Christ’s life and resurrection, of the saving power of his incarnation. It is life or death for us. There are ramifications and consequences that stretch far from our personal “piety” or “private” faith if we receive it unworthily. Participation in the mystery of Christ’s redemption must be taken so seriously, that anything that contradicts the integrity of our union (communion) with Jesus requires strict attention. The bishops are pondering the issue of “sacramental coherence” these days. It is their duty to shepherd the faithful so that we do not eat and drink judgment on ourselves. We should pray for them and for us.