Political divisions have legislatures deadlocked and stalled — not just in the United States, but also in Europe, where populist movements are gaining ground.

Meeting with Catholic legislators on Aug. 23, Pope Leo XIV proposed a way forward — by looking backward.

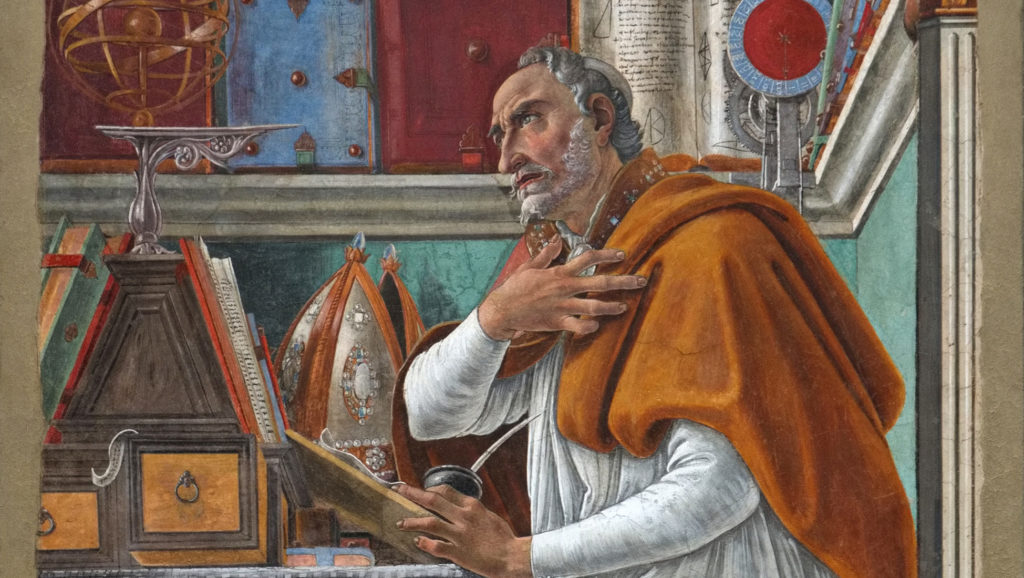

The pontiff spoke in the Vatican to a gathering of more than 200 members of the International Catholic Legislators Network: “To find our footing in the present circumstances — especially you as Catholic legislators and political leaders — I suggest that we might look to the past, to that towering figure of St. Augustine of Hippo.”

He continued: “As a leading voice of the Church in the late Roman era, he witnessed immense upheavals and social disintegration. In response, he penned ‘The City of God,’ a work that offers a vision of hope, a vision of meaning that can still speak to us today.”

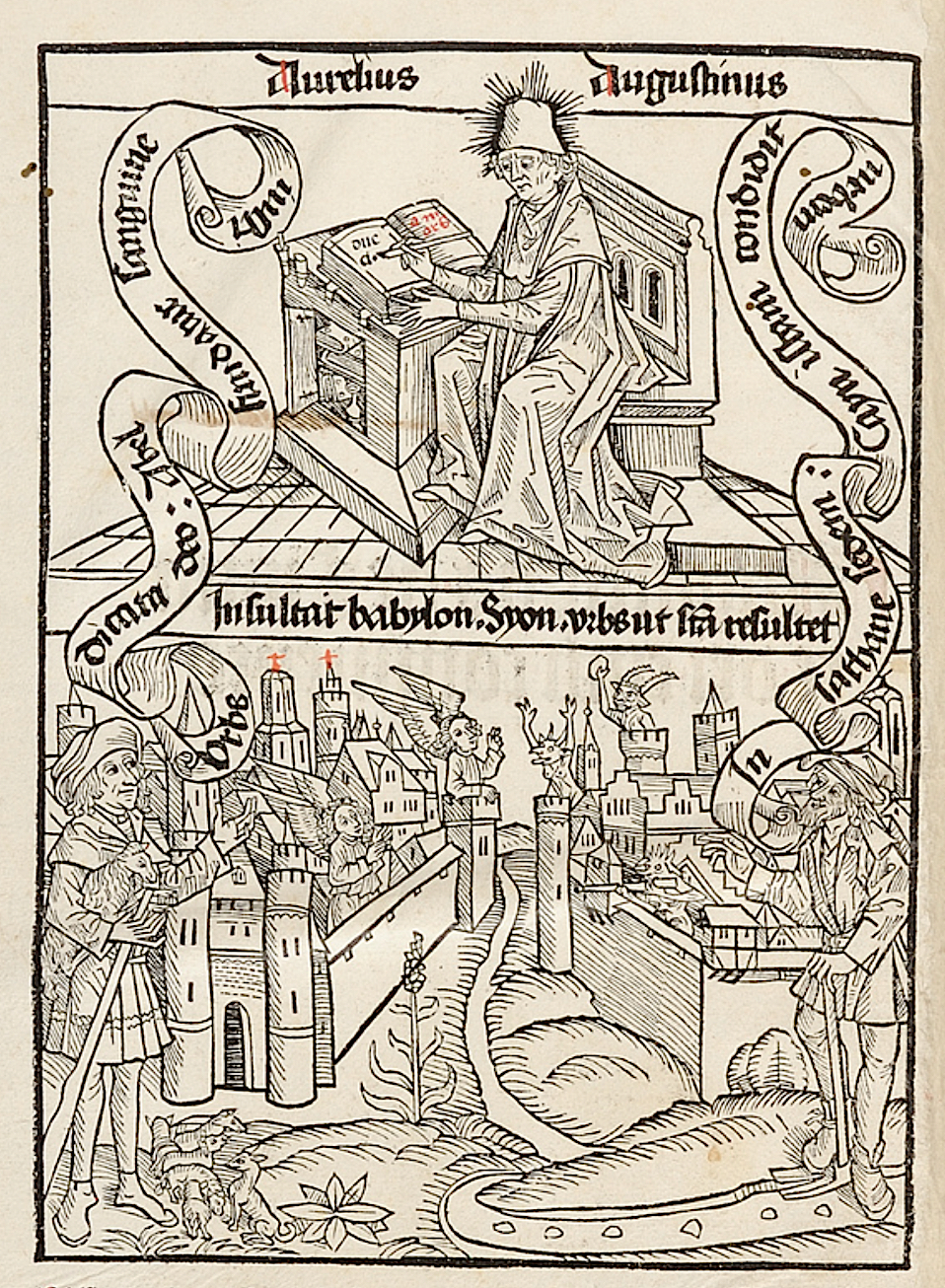

Composed in the fifth century, “The City of God” is a massive work, and it was meant to provide guidance for a world in societal meltdown and panic.

Perhaps it was a coincidence, but Leo gave this counsel on the eve of the 1,615th anniversary of the event that brought on that panic: the sack of Rome by the barbarian Visigoths in 410.

The news made its way thousands of miles, entirely by word of mouth, to the farthest reaches of the empire. The impossible had happened: Rome, the capital of the world, had been invaded and pillaged, its wealth hauled away with hostages from the aristocracy and the emperor’s own family.

From his monastery in the Holy Land, St. Jerome wrote: “My voice sticks in my throat; and, as I dictate, sobs choke my utterance. The city which had taken the whole world was itself taken.”

For many Christians the thought had been unthinkable. Rome, after centuries of persecuting Christians, had itself become Christian in the year 313. Bishops like Eusebius of Caesarea explained that the Christian empire had been predestined by God as a means of world unity, peace, and salvation.

Now this Christian hope was vanishing, and the pagan aristocrats were rushing forward to blame the Christians for the disaster. An aristocrat named Volusianus argued publicly that Christianity just didn’t work in the real world. For example, it was folly, he said, for states and armies to turn the other cheek, as Jesus had commanded, and not return evil for evil (see 1 Peter 3:9).

Some Christians began to waver in their faith, and one Roman government official, a man named Marcellinus, wrote to a friend of his in Africa for help in responding to the new spiritual crisis. His friend was the bishop of Hippo Regius, a port city in what is today Algeria, and his name was Augustine.

St. Augustine would spend the next 14 years writing his sprawling response. Marcellinus had probably expected a letter with maybe the outline of a counterargument. What Augustine produced instead was his largest book by far — about a quarter of a million words in English translation. Most scholars consider “City of God,” with Augustine’s autobiography, “The Confessions,” to represent the saint’s greatest and most characteristic work.

The finished product (which Marcellinus did not live long enough to read) is a thoroughgoing exploration of Christianity’s relationship to the state and society.

Leo, in prescribing the book to an audience of legislators, summarized its message.

Augustine taught, the pontiff said, that “within human history, two ‘cities’ are intertwined: the City of Man and the City of God. These signify spiritual realities — two orientations of the human heart and, therefore, of human civilization.’

The City of Man, he explained, “built on pride and love of oneself, is marked by the pursuit of power, prestige, and pleasure.” The City of God, “built on love of God unto selflessness, is characterized by justice, charity, and humility.”

Augustine, according to Leo, “encouraged Christians to infuse the earthly society with the values of God’s kingdom, thereby directing history toward its ultimate fulfilment in God, while also allowing for authentic human flourishing in this life.”

This is not a simplistic dualism. Augustine did not divide the world between Christian “good guys” and pagan “bad guys.” Nor did he oppose the overtly “sacred” to the merely “secular.”

Augustine insisted, “These two cities are entangled together in this world and intermixed until the last judgment affects their separation.”

In the course of his book he examined Roman history, taking frequent detours through literature, philosophy, and mythology, to make his point.

He noted that the fortunes of Rome — during its classical, pagan period — had risen and fallen. Thus, worldly success is fleeting and is no clear indication of a religion’s rightness or wrongness.

He also cited instances when Rome’s ancient heroes and pagan emperors had shown mercy instead of severity — and prospered as a result. The virtues that Volusianus had associated with Christian “weakness” had proven to be strengths when exercised by pagans.

For Augustine, the populations of the two cities could not be discerned simply through religious affiliation. He wrote, “As long as she is a stranger in the world, the city of God has in her communion, and bound to her by the sacraments, some who shall not eternally dwell in the lot of the saints.” There are some who recite the Christian creed, but nevertheless act wickedly. “These men you may today see thronging the churches with us, tomorrow crowding the theatres with the godless.”

On the other hand, among the “declared enemies” of Christianity there are virtuous people, “unknown to themselves, who are destined to become our friends.”

These foundational principles led Augustine to counsel universal charity as Christians made prudential decisions about political and social life. They might find their strongest allies in unexpected places. And they might discover that their truly dangerous foes are sharing their church pew on Sunday.

Things are not always as they seem in this world where the two cities are entangled and intermixed. Nor are events easy to judge. A catastrophe such as the fall of Rome — for all its suffering and sorrow — is less significant than the loss of a single soul (see Mark 8:36). Those in the City of Man may experience such calamities as punishments. But those in the City of God endure them as purification. In such crises, great saints are made and great sinners manifest. St. Augustine returns often to St. Paul’s assurance that “in everything God works for good with those who love him, who are called according to his purpose” (Romans 8:28).

For Augustine, Catholic leaders are better leaders when they’re better Catholics, and pagan leaders do best when they’re most like Christ. It may seem counterintuitive to show mercy instead of severity; but history shows that it is the better course.

Everything depends on what a politician (or any citizen) chooses as the ultimate love. If it is anything less than God — if it is merely the glory of a nation, for example — it will eventually lead to evil. Augustine famously asked, “Justice being taken away, then, what are kingdoms but great robberies? For what are robberies themselves, but little kingdoms?”

Leo clearly sees in the fall of Rome a distant mirror that reflects current societal crises. More importantly, he sees Augustine’s great book as a manual for effective leadership in perilous times.

He told the members of the International Catholic Legislators Network, “This theological vision can anchor us in the face of today’s changing currents: the emergence of new centers of gravity, the shifting of old alliances and the unprecedented influence of global corporations and technologies, not to mention numerous violent conflicts.”

He continued: “The future of human flourishing depends on which ‘love’ we choose to organize our society around — a selfish love, the love of self, or the love of God and neighbor.”

At the beginning of his pontificate, Leo declared himself to be a “son of St. Augustine.” He also committed himself to promoting the Church’s “treasury” of social teaching. For an Augustinian pope, that teaching takes its origin from the Gospel, but finds an authoritative interpretation in “The City of God.”

That great book — along with Augustine’s other masterpiece, “The Confessions” — will likely be the key to understanding Leo’s pontificate. One describes God’s conversion of a great saint. The other uses the same principles to describe God’s transformation of the world.