In 2015 the Reformed theologian Peter Leithart issued a “wish list” of “What I Want from Catholics.” Among the items on his list was “giving up inventions like ... the assumption.”

Eight years have passed, however, and his wish has not come true. The Church is on track to celebrate the feast in a few days, as it has since the fourth century. And long before the Church marked the feast, it celebrated the fact of the Assumption.

Indeed, Christians have, since the early days of the Church, believed that Mary, at the end of her earthly life, was taken into heaven, body and soul.

Christians in the East and West tended to mark the event in different but complementary ways. The East remembered the close of Mary’s earthly life, her “falling asleep” or Dormition. Christians in the West emphasized the beginning of her heavenly life: her Assumption.

We see the original event in the vision that is the centerpiece of the last book of the Bible. St. John beholds “in heaven, a woman clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet, and on her head a crown of twelve stars ... she brought forth a male child, one who is to rule all the nations with a rod of iron" (Revelation 12:1, 5). Jesus is the only candidate to fit the description of the male child; and the mother of Jesus is Mary, whom John sees in heaven, fully alive, body and soul.

But Mary was not the first to receive this gift from God. The Jews honored the memory of at least three other figures who — according to tradition — had been taken bodily to live in heaven. The prophet Elijah, in a chariot of fire, “went up by a whirlwind into heaven” (2 Kings 2:11).

Long before Elijah, Moses was, according to tradition, taken up in a similar way. The story appears in an apocryphal book called “The Assumption of Moses” (composed slightly before the time of Christ) and is cited in the New Testament Epistle of Jude (verse 9).

A third figure to be assumed into heaven, perhaps, is Enoch, who “walked with God: and he was no more; for God took him” (Genesis 5:24). The Book of Sirach elaborates slightly on the story (44:16; see also 49:14), as does the Letter to the Hebrews (11:5).

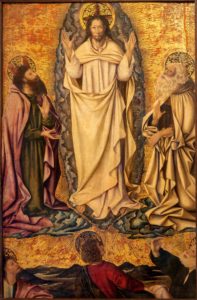

Moses and Elijah both appeared with Jesus at his transfiguration. In the Gospel accounts, both men are alive; they are embodied; and they can be seen and heard.

In the writings of the early Fathers, Moses and Elijah are often associated with the Virgin Mary, probably for this reason: All were assumed into heaven. In the fourth century, St. Ephrem of Syria sang that Moses and Elijah were able to rise to heaven because of the chastity with which they lived their earthly lives. That quality would be even more applicable in the case of Mary, who conceived her child virginally and remained ever-virgin.

The earliest Christians celebrated Mary’s life. One of the most widely circulated books at the beginning of the second century was the so-called “Gospel of Mary,” which tells the story of her childhood. There are other texts related to the end of her days, but Protestant historians for centuries were unwilling to recognize their antiquity.

The contemporary historian Stephen Shoemaker writes of an “anti-Catholic prejudice” and “bias” in his field, a “prejudice of early Christian studies against attributing much significance to the veneration of Mary.”

But Shoemaker’s work has stirred a reconsideration among scholars. His 2002 study, “Ancient Traditions of the Virgin Mary’s Dormition and Assumption” (Oxford University Press, $73), considered, in 460 pages, all the available literature in Latin, Greek, Coptic, Syriac, Sahidic, Armenian, Georgian, and Ethiopic. He followed this up in 2016 with “Mary in Early Christian Faith and Devotion” (Yale University Press, $38). He also produced in 2012 a new translation of “The Life of the Virgin” (Yale University Press, $32.50), written by St. Maximus the Confessor, an important witness to ancient traditions.

Even before Shoemaker, the tide had begun to turn. In 1998 the evangelical Protestant biblical scholar Richard Bauckham traced the Assumption/Dormition traditions to “the fourth century at the latest, but perhaps considerably earlier.”

Shoemaker and others believe the earliest textual witnesses to be from the third or even second century.

So the Assumption is no more an “invention” than the Trinity, whose doctrine and vocabulary (obscure in Scripture) were elaborated slowly over the centuries.

We’re still discovering reasons it’s good to celebrate the Assumption. In 1950, the Ven. Pope Pius XII promulgated the historical fact as a religious dogma. The world was emerging from its second global war in a 30-year span. The Holy Father lamented that his pontificate was “weighed down by ever so many cares, anxieties, and troubles, by reason of very severe calamities that have taken place and by reason of the fact that many have strayed away from truth and virtue.”

He voiced his hope that “from meditation on the glorious example of Mary men may come to realize more and more the value of a human life entirely dedicated to fulfilling the will of the Heavenly Father and to caring for the welfare of others.”

Some 73 years later, we Christians find ourselves with a different set of cares, anxieties, troubles, and calamities. Once again, as in 1950, “many” are straying “away from truth and virtue.”

With God and history as our witnesses, we’ll celebrate the feast this year. Mary, body and soul in heaven, is the sign that God wills to unite and restore and heal whatever sin and death divide.