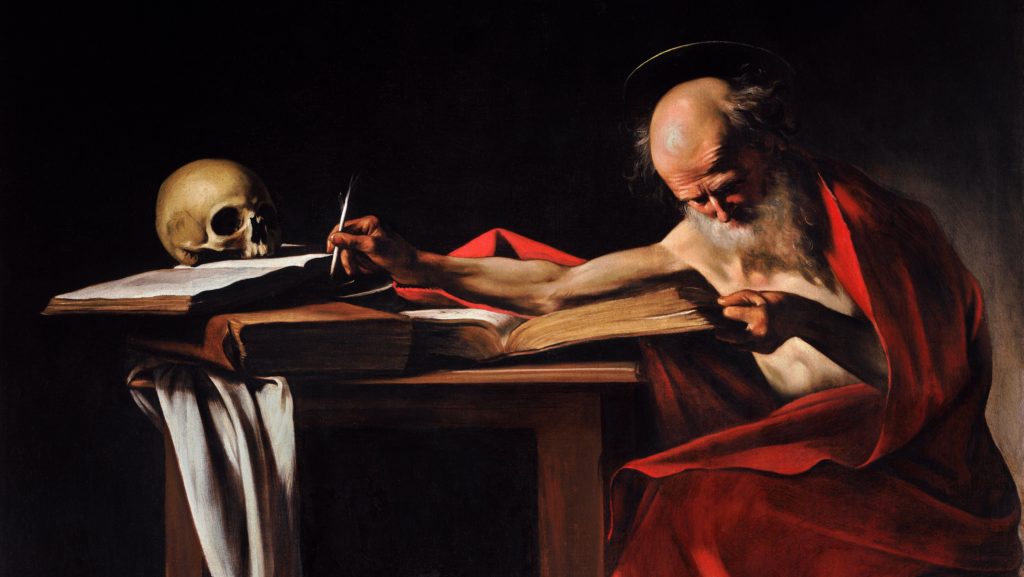

Among the items most common in images of the saints is a human skull — often placed upon the desk where the saint did his writing or other work.

The motif is called a “memento mori,” which is Latin for “Remember you must die.”

Since the first days of the Church, saints have given that advice and followed it themselves.

Indeed, the month of November stands as a sort of memento mori in the Church’s calendar. It begins with two days recalling those who have died: All Saints and All Souls. And the month ends as the liturgical year is closing and (in some climates) the last leaves are falling. Everything in creation, it seems, is delivering the message that life is brief, and all things must pass away.

Christians have an opportunity to seize the moment and use it as the saints have. For our earthly years will end, as theirs did, in death — and we want to proceed, as they did, to heaven.

Even before the coming of Christ, philosophers counseled people to reflect upon death. Knowing their earthly limits, men and women can better order their years of life. Facing the inevitable, they can begin to overcome the fear of it.

The idea appears often in the Old Testament (see Job 8:9, Psalms 102:11, 109:23, 39:4–7). St. James writes in his letter: “What is your life? For you are a mist that appears for a little time and then vanishes” (James 4:14).

The earliest Christian instance of the phrase memento mori comes from Tertullian, a second-century Christian writing from North Africa. The practice is universally recommended — and almost universally avoided, so great is the fear of death and the pain, diminishment, and humiliation that accompany it.

If we find it too unpleasant to consider our own death, perhaps we can begin by contemplating the deaths of the saints. They, after all, are by definition those who have died well.

The lives of the martyrs teach us to cultivate courage by meditating on the suffering and death of Jesus. Many of them — like St. Ignatius of Antioch in the early 100s — expressed joy and even elation that their life would soon come to resemble the life of Christ in its ending.

Most saints, however, have ended their days in ways that were less public and violent. Most saints have died of natural causes, as most of us will, and most have died in bed. Their heroism was of a quieter sort.

St. Anthony of Egypt was 105 years old in the year 356, and he sensed that his end was near. He faced death as a project that demanded certain practical tasks, and he fulfilled them one by one.

At the time, some Egyptian Christians were continuing the pagan custom of mummifying the dead and keeping their bodies above ground. Anthony wanted no part of that, and so he left instructions for his burial. He also arranged for the disposition of his few possessions, including telling his companions where they should distribute his clothing. And then he said his goodbyes as he would at any other moment of parting.

St. Ambrose, the great fourth-century bishop of Milan, fell ill at the worst time — during Holy Week, when a bishop is busiest. But he accepted his fate and took to bed, leaving his duties to a visiting bishop who was a friend.

Eyewitnesses said that on Good Friday he stretched his arms wide, in the form of a cross, and prayed silently. That night Ambrose received the Church’s last sacraments from the bishop who was filling in for him. And then he died in peace.

Almost a millennium-and-a-half later, in 1897, St. Thérèse of Lisieux was suffering what she knew to be the final stages of tuberculosis at the age of 24. She suffered physically, psychologically, and spiritually. She was severely tempted to lose faith. But she persevered in bringing even these thoughts to God and invoking the words of prayers she had known since childhood.

Thérèse faced adversities squarely and considered them all in a supernatural way. She coughed up blood, was unable to eat, and saw her own body reduced almost to a skeleton. Yet she referred everything to God. Like Jesus, she offered everything for the salvation of souls — even her spiritual torments.

Five lessons from the saints

Our own passing seems so remote, until it isn’t. What can we learn from the deaths of the saints?

- No matter your age, memento mori! It is good for us daily to remember we’ll die. We don’t have to buy a skull for the desktop. Catholic tradition gives us a prayer for this purpose, called the “Acceptance of Death.” There are many variations. Here’s one: “O Lord, my God, from this moment on I accept with a good will, as something coming from your hand, whatever kind of death you want to send me, with all its anguish, pain, and sorrow.” We probably won’t feel any authenticity in the words as we say them, at least at first. But we should give ourselves time to grow into them.

- Prepare a will and plan our funeral. St. Anthony of Egypt did both so that he would have fewer anxieties at his passing — and he would not leave his companions with any decisions to make or reasons to disagree among themselves.

- Meditate every Friday on the Stations of the Cross. It is good to know that God himself suffered death so that we would not fear it. The more we contemplate Jesus’ pains, the more we love him, because he suffered them for our sake. The more we love him, the more we wish to be like him, even in our last agony.

- Pain is inevitable, and we don’t make it easier by avoiding it. We do make it easier by fasting and otherwise denying ourselves — in other words, when we welcome pain, we grow acclimated to it. Athletes learn this. Soldiers learn it. We, too, should learn it. If we practice self-denial when we’re healthy, we’ll be better able to endure pains that are passive — that we do not choose. We can offer them up in reparation for our sins. We can offer them for the sake of others.

- Let others know our wishes (like Anthony and Ambrose). Of course, we’ll want to receive the Church’s last sacraments. We should communicate this to our caregivers and tell them how to follow up. We can even draw up such instructions, just in case we’re limited in our communication at the end.