On the second Monday of October, Los Angeles will become the largest U.S. city to celebrate the heritage, history and sacrifices of Native American nations and tribes with Indigenous Peoples Day, replacing Columbus Day on the city calendar.

The city council’s 14-1 decision on Aug. 30 to rename the civic holiday — and establish Italian American Heritage Day on Oct. 12 (the day Christopher Columbus saw land in 1492) — came after a contentious debate. Some supporters of retaining the 80-year holiday believed the Italian explorer should be honored, and not blamed for the entire catalogue of atrocities unleashed by various European colonizers on Native peoples in the Americas.

Supporters of the new Indigenous Peoples Day argued that the renamed civic holiday would be a very small, but overdue step toward recognizing and honoring the contributions of “indigenous, aboriginal and native people” that helped shape the city of Los Angeles and the country at large.

But recognizing the dignity and heritage of Native peoples is not simply a secular affair, particularly for the Catholic Church in North America, where American Catholics are looking for lay models of how to live holy lives and share their faith in challenging times. The U.S. Church held a convocation of Catholic leaders in July to discuss Catholic evangelism. Authors have floated a raft of ideas, such as the Benedict Option, and Archbishop José H. Gomez dedicated an entire pastoral letter inviting lay Catholics to take up the adventure of holiness.

But the American Church has a hidden story, now starting to become more widely known thanks to the canonizations of St. Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin and St. Kateri Tekakwitha: it already has produced many outstanding and inspiring examples of holiness in lay men and women from all walks of life — who became saints, evangelizers and martyrs for Jesus Christ — among the Native peoples of North America.

The stories and lessons of how they lived holy lives, in enormously challenging times, are gaining more attention. Pope Francis will recognize in October the first martyrs of Mexico, when he canonizes the Child Martyrs of Tlaxcala — Cristobalito, Antonio and Juan — martyred between 1527 and 1529. In the United States on Oct. 21, the Diocese of Rapid City officially will open the cause of Nicholas Black Elk, the holy man, chief and Catholic catechist of the Oglala Lakota, who died Aug. 17, 1950.

However, the U.S. Church is on track to receive dozens of recognized lay saints from Native American Catholics who gave their lives heroically in the largest mass martyrdom event that took place on U.S. soil and orchestrated by Anglo American colonists and slavers in the early 18th century.

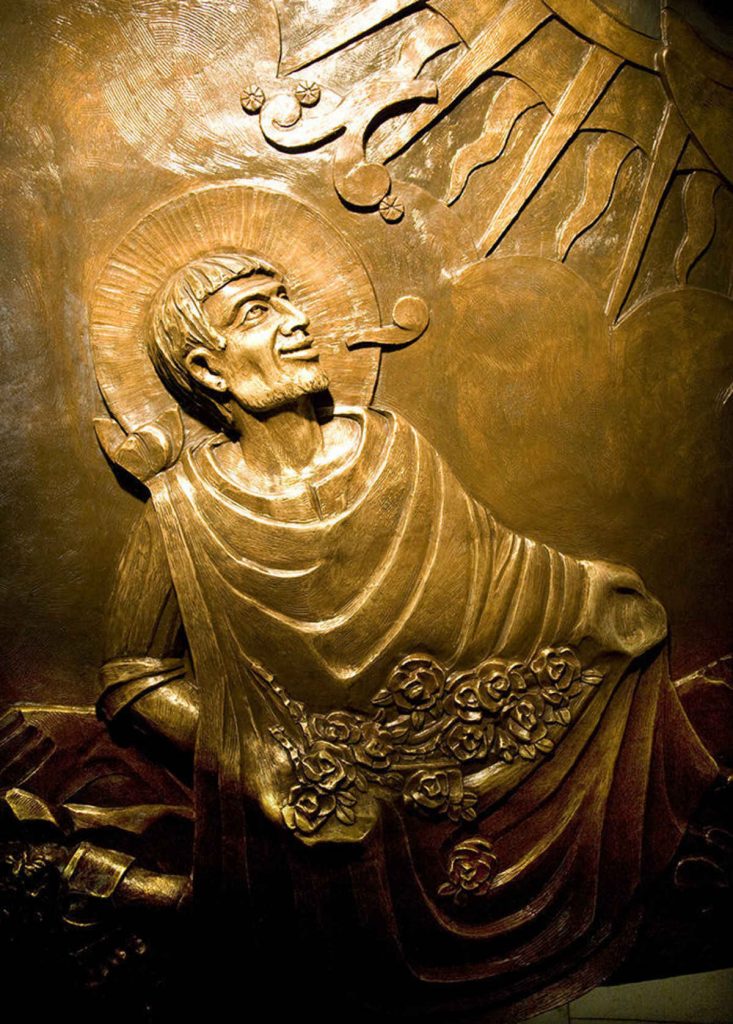

The Martyrs of the La Florida Missions cause — which will need Rome’s approval for the martyrs’ beatification — contains approximately 100 known Native American Catholics, most of them from the Apalachee nation, such as the cause’s lead martyr Antonio Cuipa, a Catholic husband, father, carpenter, community leader and catechist.

Dr. Mary Soha, vice-postulator for the Martyrs of the La Florida Missions, explained to Angelus News that the men, women and children who became martyrs of the La Florida missions could only do so because they had freely embraced the Catholic faith they received from the Spanish Franciscan missionaries and through the evangelization of Native lay catechists. They were already living out the challenge of holiness in the day-to-day of the laity, when the English launched their war to exterminate the Catholic faith, eliminate Spanish influence and enslave the Native people in Florida.

“The native people fought to defend the presence of Christ in the Eucharist and they fought to defend his kingdom,” said Dr. Soha.

The Apalachee Catholics, she explained, were a Eucharist-centric people who believed “with every cell in their body” that Jesus their creator was truly with them. They would travel long-distances for Sunday Mass, pray vespers the night before and return to their regular lives by Monday. They also had a deep devotion to Mary through the rosary. The cause’s lead martyr, Antonio Cuipa, received a vision of the Virgin Mary before he died a martyr on the cross of the Ayubale mission at the hands of the English and the Creek.

Dr. Soha said Antonio also serves as a model for Catholics today regarding how to integrate faith and evangelization into their everyday busy lives. Soha pointed out that Antonio was “the best catechist we know” in the cause. But he was also an inija (or second to the chief in managing the day-to-day affairs of his village), an engineer who constructed Mission San Luis, and a devoted husband and father to two children. He made time to give his “time, talent and treasure” to share the Gospel and build up the Church. On the eve of his martyrdom, Antonio made out his last will and testament, which illuminates his interior life and shows how “every breath he takes is in thanksgiving to Jesus.”

“He was a catechist and that was the joy of his life,” Soha said, adding that he is one outstanding example among many Native American martyrs in the cause.

Prophets of the New Evangelization

St. John Paul II started the push to elevate Native models for holiness for the universal Church, beatifying St. Kateri (1980), St. Juan Diego (1990) and the Blessed Child Martyrs of Tlaxcala (1990). But when the Holy Father visited Canada in 1984, he singled out Joseph Chiwatenhwa and his Huron-Wendat family for the “heroic manner” in how they lived their faith in the 17th century, and said they “provide even today eloquent models for lay ministry.”

Chiwatenhwa’s energy as a catechist won him the name “the Apostle with the Apostles” from a contemporary, St. Marie de L’Incarnation. He and the Jesuits had a collaborative model of evangelization, where the Jesuit priests would form key lay disciples, who in turn shared the Catholic faith with their family, their friends, neighbors and the people with whom they did business. He became the first lay person in North America to complete the “Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius of Loyola,” and the first lay administrator of a parish, until his possible — but never proven — martyr’s death in 1642.

According to biographer Bruce Henry in the book “Friends of God,” which is based on the primary sources from the 17th century called “Jesuit Relations,” Chiwatenhwa embraced the Catholic faith after he heard St. Jean de Brebeuf speak about Jesus in Wendat at his village of Ossossane. Chiwatenhwa believed the creator, whom he already loved, was revealing himself in Jesus, and took the name Joseph. Aonetta shortly afterward embraced Chiwatenhwa’s Catholic faith, took the name Marie and together they solemnized their existing marriage with a nuptial wedding. They made every effort to share the Catholic faith with their family, friends and neighbors, and committed to raising a family of saints as a Catholic husband and wife.

“The love of the one became the love of the other,” Jesuit Father Michael Knox, director of the Martyrs Shrine in Midlands, Ontario, told Angelus News.

Father Knox explained that in Chiwatenhwa’s mystical life, he showed complete abandonment to God’s will, recognizing Jesus alone as the “master of my life,” and understood that suffering provided a “sacred space” for a person to encounter the Lord.

“He lived a heroic Christian life,” Father Knox said. Given the circumstances of his life, Chiwatenhwa could end up beatified under the new category established by Pope Francis of “oblatio vitae,” or free offering of one’s life, but Father Knox said a cause for him would still require a verified miracle attributed to his intercession.

Intentional — Evangelizing — Community: The Kahnawake Option

Long before “the Benedict Option” became a topic of discussion, Native Catholics from the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) for the most part formed an intentional Catholic community that later became known as Kahnawake.

According to Jesuit biographer Henri Béchard in his work “The Original Caughnawaga Indians,” the engine of holiness at Kahnawake was the Holy Family Association, which produced many holy men and women, including St. Kateri Tekakwitha and four Haudenosaunee martyrs: Etienne (Stephen) Tegananokoa, Françoise (Frances) Gonannhatenha, Marguerite (Margaret) Garongouas and Etienne (Stephen) Haonhouentsiontaoet. The Jesuits kept pointing to the holy lives they saw there as an example of holiness that they wished Europeans would follow.

Their model of Catholic life involved praying morning and evening prayer together, going to daily Mass, adoring Jesus in the Eucharist, frequent confession and frequent reception of the Eucharist. They loved the stories of the saints, and, as their culture had a reverence for women and family, they also had a deep relationship with the Blessed Mother. They also practiced many acts of penance that even the Jesuits considered severe, but they came from a genuine love of Jesus.

St. Kateri’s own life showed how holiness grows in relationship with others: she had a spiritual mother in an older woman, Anastasia Tegonhatsiongo, and a deep spiritual kinship with Marie-Therese Tegaiaguenta, a young widow she regarded as her own sister.

Rose of the Carrier: The Incorrupt Kateri of the West

Native models of holiness have flourished in modern times no less than they did in the 16th and 17th centuries with the first wave of evangelization. St. Kateri may one day have a counterpart from the Canadian West in Rose Prince, or Rose of the Carrier Nation, who died in August of 1949 and was discovered several years later to be incorrupt.

Rose’s own path to holiness took place amid much pain and personal suffering: Canada’s government forced her to leave her devout Catholic family at age 6 to attend the Catholic Indian residential school at Lejac, British Columbia, which was unfortunately part of the government’s sustained attack on Native family, language, culture and society. She suffered badly from a curvature of the spine, lost her mother at 17 and two sisters shortly thereafter. However, Rose developed a contemplative life centered around Eucharistic adoration, Holy Communion and daily Mass — a major reason for her decision to remain at the school, where she taught Carrier children (with the religious sisters’ cooperation) how to pray and sing to Jesus in their own Dakelh language.

“The pattern of her life is very much the story of the cross,” said Bishop Stephen Jensen of the Diocese of Prince George, who is hoping that a verified miracle to her intercession, backed by ironclad documentation, will allow him to open up an official cause. He said Rose was an artist, who painted and embroidered vestments, and was well-loved as a cheerful person who put others first. Like St. Thérèse of Lisieux, the bishop said, Rose’s great holiness was hidden in life, but became renowned after her death, when people started to consider they had a saint among them when her body was discovered incorrupt.

People come from all over North America on an annual pilgrimage in July to visit the grave site of Rose, take a spoonful of dirt from her grave and pray for her intercession. Many have reported physical and spiritual healing due to her intercession. One infertile couple Bishop Jensen married 21 years ago finally had a baby after their pilgrimage to Rose’s grave.

“Her faith touches the lives of people everywhere,” he said. The bishop said the Vatican has indicated the cause can go forward once they have documented a supernatural favor was granted through Rose of the Carrier.

“Out of a great mass of testimony, we may be able to produce something to meet the test,” he said.

Evangelizing through culture,not against it

The Church is far more ready today to learn from its Native models of holiness than it was in years past. And St. Kateri Tekakwitha may be opening up the door for a wider recognition of the examples they provide to the Church today.

Mark Thiel, archivist at Marquette University, told Angelus News he personally experienced this at St. Kateri’s canonization in 2012, when a man (who was George Looks Twice, Black Elk’s grandson) sat next to him and shared his own hope that the Church would one day recognize his own ancestor, Nicholas Black Elk, as a Catholic saint. Thiel said Black Elk is believed to have signed the petition for St. Kateri’s canonization back in 1885 — and he felt St. Kateri in that moment had brought them together.

Thiel explained that giving official recognition to the sanctity of Native American holy men and women is a difficult task. The process alone can cost upward of $250,000.

“Each one becomes a big effort, and there are no guarantees of success,” he said.

Like Joseph Chiwatenhwa and other Native people who embraced the Catholic faith, Black Elk saw the faith as a fulfillment, not a break, with his own love for the creator. Like other Lakota, Black Elk only set aside those traditional Lakota practices that he did not see as compatible with the Catholic revelation. Thiel said, “For the most part, that’s not a whole lot.”

“He serves as a model for how one can be an outstanding Catholic and still practice his language, culture and, to a certain extent, his religious beliefs,” he said.

Black Elk prayed with his pipe and his rosary, and did not see a conflict between the worship he rendered to his creator as a Lakota that led him to know Jesus as well. He went to Mass every day and joined in the sweat lodge, which has been another feature of indigenous Catholicism in the Americas, which is both a time for cleanliness of body, but also cleanliness of heart.

“In effect, he was ahead of his time,” Thiel said. “He was a model for how those two ways go together.”

The Diocese of Rapid City has carried on that legacy by extensive inculturation of the liturgy, although a Lakota missal — or any translation of the 3rd edition of the Roman Missal into indigenous languages — still remains to be completed. Pope Francis’s new rules for Mass translations with the document “Magnum Principium,” however, may pave the way for bishops to make that dream a living reality for Native peoples.

Black Elk personally catechized 400 people in his lifetime and became godfather to 100 of them. When he died, Black Elk asked that God show some sign of his mercy, and an extremely powerful aurora borealis emerged upon his passing.

For American Catholics looking at how to live in their times, the cause of Black Elk highlights again the Catholic insight, proclaimed by St. John Paul II, that the faith does not destroy a culture, but uplifts a culture and its authentic traditions and values — and in turn, enriches the entire Body of Christ.

Father Maurice Henry Sands, the executive director of the Black and Indian Mission Office, told Angelus News the stories of Native Catholic holy men and women, particularly the martyrs, can be “gifts to everybody else” in the Church. Father Sands, whose family hails from the Ojibway (Potawatomi and Ottawa nations of Michigan), said the stories underline for Catholics how to live out their own faith in challenging times, and in the context of the culture and society in which they live.

He said, “They lived the life of holiness, as Native people, in saying yes to Jesus Christ.”