Two new titles offer valuable reflections on how spirituality can survive in a ‘post-secular’ age of short attention spans

For some time now, sociologists and philosophers have played with the word “post-secular” as a way of describing the cultural milieu of the early 21st century.

Popularized by the German intellectual Jürgen Habermas, “post-secular” is a notoriously elastic concept. Among other things, it’s not clear if it means the world once was secular and now is something different, or if it simply never was as secular as we thought in the first place.

However defined, “post-secular” is basically a way of acknowledging the surprising endurance of religious faith and practice despite centuries of full-throttle Western secularization.

If we choose to see it, evidence of that religious impulse is all around us, but certainly one common case in point is prayer — no matter their life situation or belief system, a staggering number of people still, at least occasionally, feel a tug to reach out and connect with God.

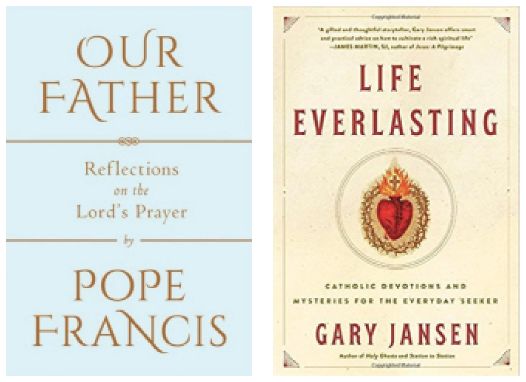

Two recent Catholic titles both reflect and feed that interest in prayer. One is by a great Catholic writer and friend, Gary Jansen, and the other is by a fairly well-known Catholic spiritual guide himself — Pope Francis.

The book by the pontiff is titled “Our Father: Reflections on the Lord’s Prayer” (Image, $21), capturing a series of brief conversations about the Lord’s Prayer between the pope and a well-known Italian TV priest and prison chaplain, Father Marco Pozza, on the television service of the Italian bishops’ conference, TV2000.

The broadcasts, nine in all, were aired last October and November by TV2000, and involved pieces of Father Pozza’s conversation with Pope Francis, followed by exchanges with some well-known Italian layperson, either religious or secular, including novelists and TV stars.

In late November, the Vatican publishing house released a book version of the conversations, and the English translation went on sale March 13, timed to coincide both with the fifth anniversary of Pope Francis’ election to the papacy and with Easter.

The book caused a minisensation when it came out, driving headlines around the world along the lines of “Pope wants to change the words of the Lord’s Prayer.”

In the course of his conversations with Father Pozza, Pope Francis said he didn’t like the phrase “lead us not into temptation,” arguing it’s a misleading translation because it can imply that it’s God, not Satan, who tempts human beings to sin.

In truth, of course, this never had anything to do with changing the “words” of the prayer. The Koine Greek term in the New Testament for being tempted is “peirasmos,” and nobody’s talking about changing it or any of the other words of the Bible.

Instead, what Pope Francis was talking about was how to translate those words into modern languages in a way that accurately conveys their meaning, which is an entirely different, and terribly complicated, subject.

(There’s some irony in the fact that he was dispensing translation advice hard on the heels of issuing a decree transferring authority over translations for liturgy away from Rome and back to local conferences of bishops, but that’s another kettle of fish.)

In addition to the exchange with Father Pozza, the English edition is fleshed out by excerpts from other papal remarks, including catechetical lessons from his general audiences, homilies and Angelus addresses, in which he addresses some of the same points.

The book also contains an afterword by Father Pozza, reflecting on some of his experiences of encountering moments of prayer among inmates he’s met as a prison chaplain in the Italian city of Padua.

The book could easily be read in one sitting, but I suspect it’s going to be more often utilized in bite-sized pieces, as a stimulus for personal prayer and reflection.

In my mind’s eye, I envision it on thousands of night stands or reading tables scattered all around the world, wherever someone chooses to unplug from the world for a moment to take stock of themselves, their lives and their relationship with what Pope Francis describes as a God who’s a loving, intimate Father.

Another book with the same future likely is “Life Everlasting: Catholic Devotions and Mysteries for the Everyday Seeker” (TarcherPerigree, $17) by Gary Jansen, an old friend and the publisher for several of my own books with Doubleday and now Image. It also went on sale on March 13.

In addition to being a superb publisher, Jansen is a nifty spiritual writer in his own right, as his new book attests.

Jansen, in a sense, is almost a “guide for the perplexed in a post-secular age,” meaning people who haven’t been living under rocks and therefore know full well the challenges to belief out there, but who nevertheless sense the lure of the transcendent and are open to ways to encounter it, whether through prayer and worship, the experience of the miraculous, or however else God may sneak into their lives.

Jansen offers simple prayers and actionable disciplines for those contending with a variety of common problems or scenarios:

• Looking for protection and guidance in times of darkness? Pray to St. Michael.

‚Ä¢ Feeling lost and abandoned? St. Gabriel’s got your back.

‚Ä¢ Seeking strength and healing? Visualize Jesus’ Sacred Heart.

• Needing to decompress? Pray the rosary.

• Gripped by fear? Appeal to St. Francis de Sales.

‚Ä¢ In need of a quick solution to an urgent problem? Look to St. Expeditus. (That’s my personal favorite, since it just seems such an apt devotion for an age of frenzy.)

As with the pope book, Jansen’s volume can be read with profit straight through, but that’s probably not its natural destiny.

Instead, it’s a resource to keep handy and dip in and out of, as a way either of testing the waters of prayer or moving steadily deeper into them.

In the interests of full disclosure, I should confess that I’m about the last person anyone should turn to for spiritual advice. I’m usually about as spiritually tone-deaf as they come, falling back on that old saw about my work being my prayer. (In my defense, my prayer actually is just like my work — rushed and half-baked most of the time.)

In this case, however, my unsuitability as a guide may be precisely the point. If I see the potential of these titles to enrich my own prayer life, then God knows they ought to work for anyone.