The Catholic liturgical calendar honors All Saints’ and All Souls’ days in early November, but this month is also set aside to recognize the rich history of black American Catholics — National Black Catholic History Month was initiated by the National Black Catholic Clergy Caucus of the United States in 1990.

November was selected because it contains commemorative dates for two prominent black Catholics: St. Martin de Porres, whose feast day is Nov. 3, and St. Augustine of Hippo, whose birthday is Nov. 13. These are just two of numerous faithful followers of God of black or African origin who have been elevated to sainthood over the centuries. There are currently four additional notable black Catholics on the road to sainthood for living, sharing and supporting the Faith.

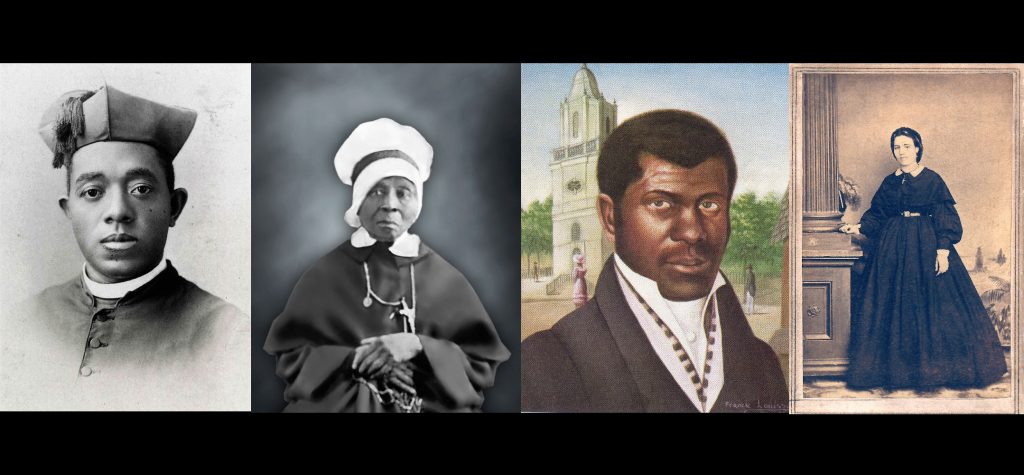

Father Augustus Tolton

rn

rn

rn

Father Augustus Tolton has been designated a Servant of God, which means he is being investigated for canonization, which is the first step in the sainthood process. He was a former slave whose owner baptized all of his slaves as Catholic. A young Augustus was befriended by his parish priest, who saw great faith in him and worked to secure his acceptance into a seminary. He was rejected by every American seminary until he was finally accepted into St. Francis Solanus College. Upon graduation he was accepted to Pontifical Urbaniana University in Rome.

Ordained in 1886, Father Tolton returned to the U.S., where he was the first black Catholic priest in the country. He became pastor of St. Joseph Church in Quincy, Illinois, where he was charged with growing a black Catholic community. He became well-known for his sermons and educating poor young black children. His congregation included both black and white parishioners, which caused discord with a neighboring priest who was not happy with Caucasians providing financial support to the black parish. The disgruntled priest lobbied the bishop to force Father Tolton to observe the segregated system or risk being transferred.

Father Tolton relented to continuous pressure and three years later accepted another appointment where he received a very warm welcome from a burgeoning apostolate of black Catholics in Chicago. His appointment to St. Monica’s afforded him the opportunity of ministering to a mostly poor black community of nearly 30,000. He received support from people like Mary Elmore, a Franciscan tertiary and board member of the Visitation and Aid Society. After attending Mass with him one day, she wrote, “Poor Father … he is left to struggle alone in poverty. … We are witnesses of his ardent charity and self-denying zeal.” He also received financial assistance from Sister Katharine Drexel, foundress of the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament (SBS) in Philadelphia, who is now a modern-day saint.

Father Tolton died at 43 from heat exhaustion in 1897, without seeing the completion of his work to construct a larger building to hold the growing number of black parishioners. His distinction of being the very first black Catholic priest in the United States has served to pave the way for thousands who served after him.

Mother Mary Lange

rn

rn

rn

Mother Mary Lange was born Elizabeth Clarisse Lange in Santiago de Cuba in 1794 in a French-speaking community. She was well-educated and her family had high social standing, though little more is known about her early life.

She left Cuba in the early 1800s and eventually settled in Baltimore, Maryland, where she soon realized there was a great need to educate African-American children, so she opened a free school in her own home. In 1828, she was approached by Father James Joubert, SS, who asked her to start a school and a women’s religious order with a mandate to teach girls of color.

In addition to the school, the archbishop also authorized the establishment of a religious order for women of color, something unheard of at the time. With the acceptance of their vows of poverty, obedience, and chastity, the order of the Oblate Sisters of Providence was established in 1829, with Mother Mary Lange designated as its first mother superior. In the years and decades that followed, the order eventually founded schools across 18 states, in Cuba and Costa Rica.

At its height in the 1950s, the Oblate Sisters of Providence had about 300 members, but, like many religious orders, they’ve experienced a significant decline and currently have approximately 60 members serving in Baltimore, Maryland; Miami, Florida; Buffalo, New York; and in Alajuela and Siquirres in Costa Rica.

Mother Lange lived to see the 50th anniversary of the order she founded with just three other women before she died at the motherhouse in Baltimore in 1882. She was declared a Servant of God in 2006.

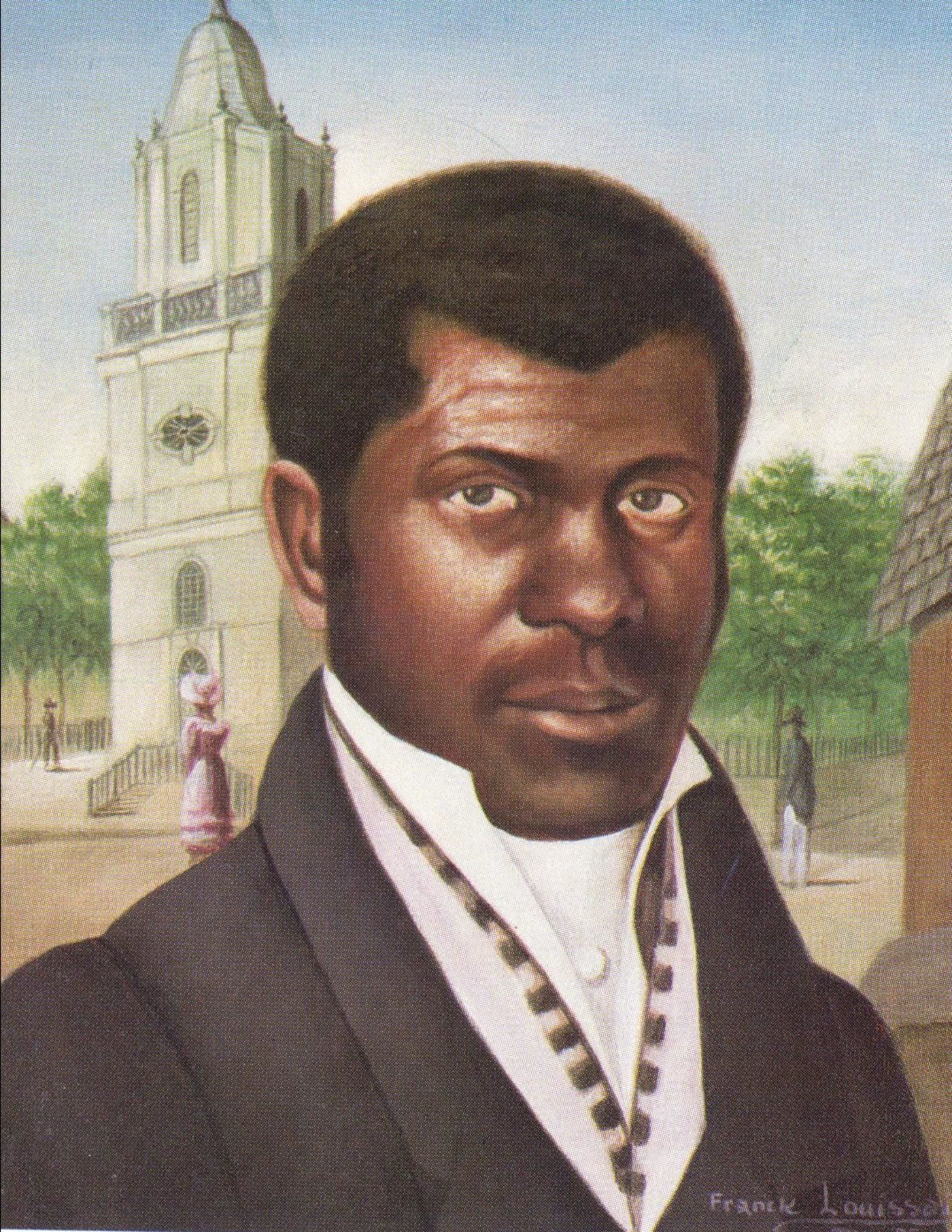

Venerable Pierre Toussaint

rn

rn

rn

Born in Haiti, Venerable Pierre Toussaint was born a slave and was baptized Catholic in accord with his owner’s wishes. As a child he was educated and served the family, who had a sugar plantation. In 1787, the family fled to New York amid rising racial tensions, bringing five of their slaves with them, including Toussaint. Servitude was still an accepted practice in the U.S. at the time and he was placed into a hairdressing apprenticeship for wealthy white socialites.

In the early years of his servitude his earnings were used to support the family, which had lost everything following an uprising in Haiti. His owner reportedly died of a broken heart, leaving his wife a widow and Toussaint responsible for her care. The widow remarried and when she passed away he was freed from servitude. He began to save money and won freedom for his fiancé and sister. He shared his eventual wealth with the Catholic Church and attended Mass every day for 66 of his 87 years.

Toussaint was dedicated to the theological virtue of charity. He cared for the sick by taking them into his own home and nursing them back to health. He also visited the ill in facilities regarded as highly contagious to provide supplies and comfort. He leveraged his relationships with his wealthy clients to help raise funds for the Church lending financial support to St. Elizabeth Ann Seton’s orphanage, the first black Catholic school at St. Vincent De Paul and the construction of the first St. Patrick’s Cathedral building on Mulberry St. in Manhattan.

Following his death in 1857, Toussaint’s remains were transferred to the current St. Patrick’s Cathedral on 5th Ave. He was the first layperson bestowed the honor of having his remains interred in crypts previously reserved for Church princes. In 1991, Toussaint was designated as a Servant of God and five years later declared venerable by Pope John Paul II.

Venerable Henriette Delille

Henriette Delille was born in New Orleans to a father of French descent and a free woman of color in 1813. The pre-emancipation society of the state during that era sanctioned common-law unions between individuals of European and mixed-race origins. As a young woman, Delille was being groomed by her mother to be joined in a common-law union — an idea that was abhorrent to the budding saint outside the sacrament of marriage. But mental illness afflicted her mother. A court declared her incompetent and granted Delille control of the family’s assets.

That monetary fortune was used to care for her mother and the remaining assets were liquidated to form a religious order initially called the Sisters of Presentation, which was not sanctioned by the Church. They served the elderly, children of color and the poor. In 1837, it was recognized by the Holy See and the order was renamed the Sisters of the Holy Family. While it continued to do good works, the New Orleans Catholic community did not recognize the religious order and the sisters were prohibited from wearing a habit until after the Civil War.

In 1881, the Sisters of the Holy Family purchased the Orleans Theater and transformed the space into a school and convent, using the ballroom as a chapel. The order celebrates its 175th anniversary this month. In the spirit of its foundresses and early predecessors, the order has continued to serve youths, the elderly and the needy members in New Orleans and other Louisiana cities, in Texas, California, Washington, D.C., Oklahoma, Alabama, Florida, Belize, Panama in Central America and Benin City in Nigeria, Africa.

Sister Delille died in 1862. She was declared a Servant of God in 1988 and named venerable by Pope John Paul II in 2010. If canonized, she will become the first woman of African-American descent to be elevated to sainthood.

Local influence

The spiritual influence of these saints-to-be can still be felt today, both locally and throughout the greater Church. Father Tolton’s journey helped lay the groundwork for later African-American clergy members. To date, there have been 24 black priests elevated to bishop. Currently, there are eight living black bishops and one of them has a direct connection to the Archdiocese of Los Angeles: Bishop Gordon B. Bennett, SJ, who is now retired, has educated students at Loyola High School and Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles.

Another local connection is through the Sisters of the Holy Family, who opened Regina Caeli High School for girls in Compton in 1962 and served as faculty members until its closing in 2002, educating thousands of predominantly minority students over the course of 40 years. Upon the school’s closing, the student body at Regina Caeli was 57 percent black and 42 percent Latino.

Interested in more? Subscribe to Angelus News to get daily articles sent to your inbox.

To learn more about the history of the black Catholic community in the Los Angeles Archdiocese, contact the African American Catholic Center for Evangelization at 323-777-2106 or via email at [email protected].

To learn more about the process of canonization, go to the website of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) at www.usccb.org

AÔøΩ