Rodrigo Duterte, president of the Philippines, Asia’s only predominantly Catholic and Christian nation, has doubts about original sin.

In a recent speech at a technology summit in the southern city of Davao on June 22, Duterte revealed his rejection of the story of creation and the fall and called the idea that all of us are born with sin “a very stupid proposition.”

Further, he wondered, “Who is this stupid God? He’s really stupid. You created something perfect, and then you think of an event that would tempt and destroy the quality of your work.”

Wrongly, I think, Duterte was said to have called God “stupid.” The headlines talked about him “insulting” the Supreme Being. That is not really accurate.

He has insulted our Christian understanding of God. Or rather, his understanding of the Christian understanding of God, something much different from God himself and probably from our doctrine, too.

There is, of course, an irony in Duterte speaking about original sin that is beyond parody because he himself is a great example of the same.

His verbal excesses (let us leave his violence and ruthless tactics to restore order aside) and provocations are certainly well known, even in a day when, around the world, leaders’ casual remarks are unusually careless or needlessly and disingenuously tendentious. Half-baked, thy name is Twitter!

The president was defended by staff as exercising his right of free speech. Free it was, reckless, also, setting a new standard for ignoramus public utterance, but at least he puts his cards down on the table.

There are many in the world today, especially in the elite of the Western world, who question basic truths of revelation. They are only more cautious and hide their attack on belief behind platitudes of relativism.

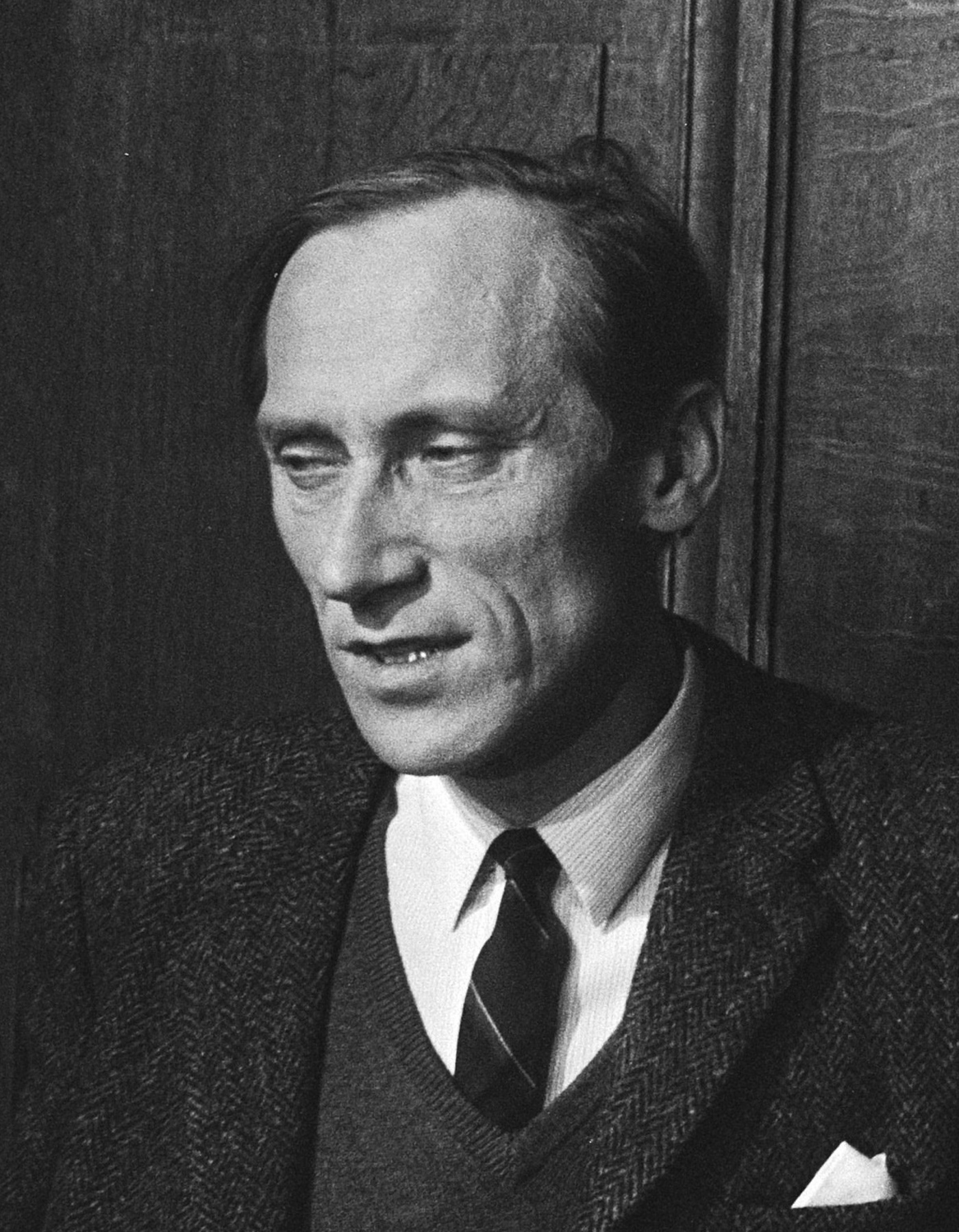

What surprised me about Duterte’s outburst is the similarity of his argument with one devastatingly critiqued in Leszek Kolakowski’s “Religion If There Is No God.”

Kolakowski, a Polish philosopher who died in 2009, was a brilliant critic and historian of ideas. His three-volume history, “Main Currents of Marxism,” is an important marker in the intellectual life of the 20th century and beyond.

Because of his dissidence of orthodox Marxism, he was exiled from Poland, and taught mostly at Oxford (with a brief stint at Berkeley, of all places), which afforded his ideas much more attention than they would have received in Warsaw. He wrote very profoundly about the philosophy of religion, particularly in his book on Pascal, titled “God Owes Us Nothing.’

In “Religion If There Is No God,” Kolakowski undertakes a philosophical defense of the doctrine of original sin. Published in 2001 by St. Augustine’s Press, there are two paragraphs that are a perfect commentary on poor Duterte’s rant.

Let us now consider the moral argument against the doctrine of original sin. It points out that belief in a merciful and loving God is strikingly incongruous with His apparently bizarre, capricious and vengeful conduct as it is revealed in the myth of the fall of man, his exile, and redemption. If this argument has any foundations, then it should be asked — and inevitably this is the first question that the annals of Eden must provoke — how is it possible that millions of people have believed in a story which, on the rationalist account of it, glaringly defies all the principles of morality and of common sense handed down by the same teachers who have been responsible for perpetuating the history of Adam and Eve?

The question whether or not it is just cruelly to punish mankind for a petty offense committed by an unknown couple in the remote past is not an intricate theological puzzle which can only be solved by highly trained logicians or lawyers; it is a problem easily accessible to illiterate peasants, and one wonders how people were induced to give credence to this kind of absurdity and why mankind had to wait for eye-openers Helvetius or Holbach before it would recognize its own amazing stupidity.

Or why we were waiting for Duterte, for that matter. Now the answer:

In fact, Christians have never been expected to believe in the story of the fall as retold and travestied by rationalists. It is not even material to genuine religious understanding whether or not they accepted in a literal sense the biblical account of what happened in the primeval garden. The history of Exile, one of the most powerful symbols through which people in various civilizations have tried to grasp, and to make sense of, their lot and their misery, is not a “historical explanation” of the facts of life. It is the acknowledgement of our own guilt: in the myth of Exile we admit that evil is within us; it was not introduced by the first parents and then incomprehensibly imputed to us. If people had really been taught that Adam and Eve were responsible for all the horrors of human history, that unfortunate couple would surely have been cursed and hated throughout the history of Christianity. … Instead of devolving the responsibility for our misfortunes on a pair of ancestral figures we admit, through the symbol of our Exile, that we are cut out of warped wood (to use Kant’s metaphor) and that we do not deserve to lead a carefree, happy and idle life; an admission that does not strike one as absurd.

Duterte’s retelling of the fall of man hopes to inspire us to think it absurd. But according to Kolakowski’s thinking, it is not just absurd but hopeless to have a vision of human life without the fall because that doctrine contains the seeds of redemption. Deny original sin and then you must deny the Redeemer.

The misery that we live in this world was not the intention of the Creator, but is the result of human freedom that chooses evil. Evil and suffering, says Kolakowski, are “ontologically coupled, so that no evil fails to bring retribution.”

Realistically, we live in a world made miserable by human freedom. It is realism that asserts with Kolakowski that apparently we do not deserve (or at any rate, are allowed, even in this age of entitlement) to live a carefree life.

Duterte has done us a favor in offering to be the poster boy of those who reject the Christian view of embattled humanity, struggling with evil both within and without the soul. What does the president offer as an alternative of the vision of the fall and redemption? He apparently thinks his view of the world is liberating.

Jesus said, “Pray for our enemies,” and part of our prayer for Duterte is that the Lord use his effusions to clarify our understanding of God and revealed truth.

Msgr. Richard Antall is a Cleveland priest. He was a missionary in El Salvador for 20 years and served as moderator of the curia for the Archdiocese of San Salvador. He is the author of “Witnesses to Calvary: Reflections on the Seven Last Words of Jesus” (Our Sunday Visitor, $13).