The connection between the body, the soul, and the divine is one that permeates every aspect of the Catholic faith.

But can that connection be made, and sustained, by looking at a still image? That’s a question that’s been the source of a fair share of debate, and even violence, over two millennia of Christianity.

The holy art form of iconography has mesmerized and perplexed audiences since the primitive Church, when icons began as small paintings of martyrs, saints, and symbols brushed on the walls of the catacombs in Rome by persecuted Christians.

Even today, iconographers begin each day of painting with a dedicated prayer, which, in part, tells the story of the original iconographer, St. Luke the Evangelist.

It begins: “O Divine Lord of all that exists, You have illumined the Apostle and Evangelist Luke with Your Most Holy Spirit, thereby enabling him to represent the most Holy Mother, the one who held You in her arms and said: ‘The Grace of Him Who has been born of me is spread throughout the world.’ ”

Tradition tells us that Luke painted the earliest icons of the Blessed Virgin Mary during her lifetime, sometime following Pentecost.

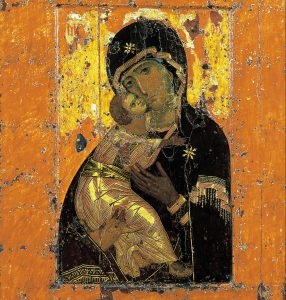

Luke is credited with painting the first “Hodegetria” icon (“she who points the way”), which was brought from Jerusalem, enshrined at the Hodegon Monastery in Constantinople, and regularly paraded through the streets. The original painting vanished after the fall of Constantinople, but the “Hodegetria” is one of the most widely copied images of the Blessed Mother.

Although officially credited to an “unknown” artist, Luke also has ties to one of the most venerated Byzantine icons, Our Lady of Vladimir. Some traditions say that the icon was painted on a plank of wood from a table that belonged to the Holy Family.

The story of the table is attached to several other icon paintings of the Blessed Virgin, including the “Salus Populi Romani.” Pope Francis is known for his particular devotion to the “Protectress of the Roman People” and spends time in prayer with the icon at the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome, leaving flowers before and after every papal journey.

Some scholars believe that the Marian icon authorship of Luke was an 8th- and 9th-century invention created during the Iconoclast Controversy in order to imbue the icons with a sense of divine authority.

The tumultuous period saw Popes Leo III and Constantine V banning the veneration of religious images in all forms (for fear of idolatry), leading to the destruction of icons and persecution of supporters, known as iconodules. This included the many monks who painted icons and were branded on the forehead and tortured as a warning to others.

Around 100 years later, icon veneration was restored, a milestone still celebrated today by Eastern Christians as the “Feast of Orthodoxy” on the first Sunday of Lent. Through around the 12th century, the Byzantine style of icons remained popular in the West and East, but the spread of Orthodoxy across Eastern Europe saw the Byzantine tradition flourish there.

Eastern Orthodoxy places great faith in the stories and traditions of icon paintings and their origins in theology traced back to the incarnation — Christ being the icon of God.

The traditional artistic methods and teachings of the icon are still being practiced today. The Prosopon School, with studios in locations throughout the United States, Russia, and Europe, was founded by master iconographer Vladislav Andrejev. His son Dmitri Andreyev is also a Prosopon instructor. The school welcomes students from all faith and artistic backgrounds.

Edward Beckett, a working artist and iconographer instructor in the Prosopon teaching program, is chair of the Icon Guild of Southern California. He leads intensive workshops throughout the state and shepherds students through a nine-month series of classes, including from his home studio in Altadena. Students work on the creation of a single icon.

Beckett says his students are largely Christian, although one secular student once joined his class just to study the egg tempera technique (the primary painting medium through 1500, after which it was replaced by oils).

Beckett emphasizes that icons are religious artworks and should be created with “faith and attention” in order for the piece to go into authentic “service.” This is when the icon has been finished — according to the over 20 steps the Prosopon School teaches — is blessed, and then given to the recipient. “The icon is an adjunct to prayer,” Beckett explains.

For members of religious orders, the icons are deep in service, personally and with the public. Brother Teresiano M. Madrigal, CFR, was involved in a prison ministry while stationed in Honduras.

He created copies of icons to give to prisoners and even had an image hung in the National Penitentiary in Comayagua, which suffered a tragic fire in 2012, killing nearly 400 inmates, of whom he knew a few. Madrigal also finds the icons an invaluable part of consecrated life. “It spoke to me. It brought me to prayer,” he told Angelus News.

On a recent Saturday, Beckett gathered a small group of icon painters for their monthly class, which included some nearing the end of the elaborate multi-step process and one who was just beginning her journey.

Juna Bae, a trained artist from London, always had an affinity for icons, citing those hanging in the National Gallery as some of her favorites. Beckett’s youngest student that day was high school freshman Aiyana Harris, who has taken classes with him for two years.

Another student, Barbara Wampole, has studied icons for nearly a decade. She went to the prestigious Cooper Union in New York City but now focuses on more contemplative arts. In addition to the icons, she practices “pysanky,” or traditional Ukrainian egg painting.

Karen McClintock has been taking Beckett’s class since February, after being drawn to the icons following a pilgrimage with an Orthodox spiritual director.

“It’s meditative, it’s creative, it’s challenging, it’s exciting to get to new steps, but to come here and spend eight hours with like-minded people listening to Gregorian chants and focusing on the saints is not a bad way to spend a Saturday,” she mused.

Beckett’s studio is perfectly serene, as students work in silence following a brief opening lesson and intoned prayer. Like an alchemist, Beckett helps mix colors for students from pure pigment powders in tiny jars with various ingredients, almost all of them natural.

Egg yolk and white wine make up the egg tempera paint that is traditionally used. The Prosopon School favors the Russian-Byzantine transparent style of painting, also known as the “membrane” style. This is different than the “Greek” style, where colors are usually painted solid.

“We put highlights on, then we put glazes on, or floats,” Beckett says. “We do that three times to develop the image. At the end of that, you have some places where you can see all the way through to the board. The white board is a symbol of the uncreated light of God.”

Each stage of the process is identified in spiritual terms. Highlights are “angelic” and “cosmic”; lines are “alpha” and “omega.” The icons themselves are also represented in a symbolic way. Beckett describes it as “mystical.”

“Usually, the ears, mouths, eyes, and forehead have meaning, as in, ‘Is this an angel that listens? Is this a saint who speaks?’ St. John the Theologian has his fingers to his lips because it’s not about his speaking, it’s about his theological thinking. Different saints and angels have their own personalities.”

The things that make classes like Beckett’s special — the prayers, chants, 20-plus steps, particular terminology — all drive home the notion that icons are not mere religious images, or even simply devotional objects.

It’s a belief that explains the seemingly inverse appearance of the figures in icon paintings.

“We expect directional lighting,” explains Sue Forrest, an iconography teacher in Modesto who attended the Iconographic Arts Institute in Mt. Angel, Oregon. “The icon doesn’t have that. The light is coming from that figure, which is indirectly a reflection of Christ in him.

“The reverse perspective is a spiritual thing. So things get bigger as they get further back. You’re the focal point, looking into the spiritual world that is unfolding.”

Painting icons is slow and meditative. It demands the stillness of hand, working with the material, not against it, but promises an epiphany for the soul. There is a slow reveal of light and color; a glimpse of the spirit contained within every layer. As the tongues of paintbrushes work over the board, each painter is in communion with the icon through unspoken prayers.

Once finished, the painting is “baptized” in oils that seal the egg tempera so it can cure. It is traditionally applied with the hands. Clay, animal skin glue, burnishing stones, gold leaf, and the painter’s own breath are also applied to the image, putting the artist intimately in touch with the icons’ ancient origins.

“It’s a whole spiritual journey. We call it the journey of light,” Beckett says.

“We’re an uncut diamond,” he tells the class before they begin a full day of painting. “We’re a stone with possibilities. As we grow older, our experience gives us facets. ... Our purpose is to get to the point where we have facets all over our diamond. If you think of the saints ... they are giving light back to the world.”

One of those saints, John of Damascus, once wrote that “through the painting of images, we are able to contemplate the likeness of His bodily form, His miracles, and His passion, and thus are sanctified, blessed, and filled with joy.”

That’s a pretty accurate description of what Beckett’s classes strive for.

“We’re working on our souls,” Beckett says. “And that’s when we’re truly working our Christian mission. That’s where the light is going out into the world.”