“I think one should remember that this is something coming from memory.”

So begins a scratchy recording at the start of “Hesburgh,” the documentary film that takes its name from Father Theodore M. Hesburgh, CSC.

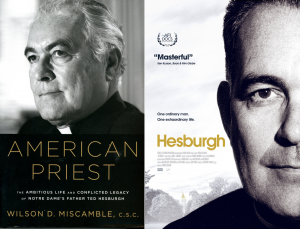

The 2019 film chronicles the life of the 35-year president of the University of Notre Dame, in South Bend, Indiana, using mostly excerpts from his own autobiographical writings as the basis for the narrative.

Its portrayal of Hesburgh as heroic and stately is based on the memories of its subject and those who knew him: friends, family, confreres, and allies. It is spectacular, beautiful, and compelling, yet, importantly, one should remember that it is coming from memory.

“I can recall my father always telling my mother that she ‘piled it,’ tended to exaggerate things,” the recording continues. “And I may have inherited some of that Irish trait.”

If the quasi-autobiographical “Hesburgh” can be accused of piling it, then its confrere, “American Priest: The Ambitious Life and Conflicted Legacy of Notre Dame’s Father Ted Hesburgh,” by Father Wilson D. Miscamble, CSC, aims for a more balanced take.

Miscamble portrays Hesburgh as a man in conflict with himself, totally dedicated to his priesthood but trying to balance his Catholic faith with the desire to be a protagonist in the civil rights movement while elevating the school’s academic prestige.

Through interviews, books, historical records, and some of his own memories of his coreligionist, Miscamble drafts an honest and nuanced narrative that at times conflicts with the narrative in “Hesburgh.”

According to Miscamble, Hesburgh’s public version of his relationships with St. Pope Paul VI, Presidents John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon, and even successor Father Edward “Monk” Malloy, CSC, were rose-colored compared to reality.

There was hurt and loss between the broken relationship of Hesburgh and the pope, anger at Kennedy for distancing himself from his Catholic roots, and distaste when Nixon championed Hesburgh’s “15-minute policy” to fight campus protests, and, most importantly for the priest who dedicated his life to Notre Dame, hurt at being left out of decisions made after his 35-year presidency had ended.

For all its historical nuance, Miscamble’s work is clearly the superior of the two, filled with more accurate scholarship than the largely autobiographical film, and thus recording more honest nuance. And yet, Miscamble’s work still suffers from a slight bias and cynicism of which he warns the reader from the beginning:

“I began to think about writing of Father Ted and Notre Dame out of a presentist concern to understand for myself and, I hope, to explain to others how events had come to pass that Notre Dame’s mission as a Catholic university had become so contested,” Miscamble writes in his introduction. “Readers must be aware of this perspective at the outset because it still operates and unquestionably it influences the perspective of this book.”

Anyone familiar with Miscamble’s work, not merely as a historian but as an activist for Catholic education, knows that Notre Dame’s invitation of President Barack Obama for its 2009 commencement address is a sticking point for the biographer in terms of Notre Dame’s Catholic identity.

Miscamble, like many others who protested and disavowed the invitation, was aghast at the decision by the country’s most well-known Catholic school to award a politician who supports abortion with an honorary doctorate.

Miscamble’s discussion of Hesburgh’s position on abortion is what most jarringly smacks of cynicism throughout the book. Though his historical investigation questions at time the extent of Hesburgh’s impact on certain causes, his criticism of Hesburgh’s lack of pro-life activism betray the author’s opinion into the university president’s legacy.

At multiple points, Miscamble criticizes Hesburgh for what he chronicles as largely a pragmatic decision. According to Miscamble’s argument, Hesburgh’s cause of choice was civil rights, and through a flawed rationale Hesburgh decided that abortion issues were a distraction he could not afford.

There are times when this criticism makes sense; for example, when recounting Hesburgh’s decision to move away from pro-life rhetoric after Yale students hissed at him during a Terry lecture in which he included defense for the unborn among civil rights issues.

However, at other points, Miscamble seems to tack Hesburgh’s life-issues ambivalence to unrelated legacies. As a result, Miscamble beleaguers the reader with this non sequitur while still failing to completely address Hesburgh’s failed legacy in life issues.

“Hesburgh” also brings up the 2009 invitation of Obama, even though the contentious event did not include Hesburgh as president, largely just to make two points: that the president cited Hesburgh for his work on the civil rights commission as essential for his election, and that Hesburgh confirmed his much-criticized successor in his decision to invite the pro-choice president.

In making these two points, the movie ironically supports the view of the Hesburgh legacy that Miscamble much maligns, in claiming the presidential commencement address as a win for Hesburgh’s civil rights campaign, it conveniently avoids acknowledging basic Catholic teaching on abortion.

Though Miscamble criticizes Hesburgh’s pro-life stance at inappropriate times, “Hesburgh” does show that the priest’s legacy is flawed because he wouldn’t address life issues publicly. As a result, the issue continues to be sidestepped or ignored, even during appropriate times to criticize abortion and Hesburgh’s lack of action against it.

There is a sense that these two works need each other — the explicit hagiography of “Hesburgh” with the nuanced, if at times cynical, analysis of “American Priest.”

The topics these works cover, civil rights, anti-Catholic prejudice, and the role of the Church in education, are far from settled, and the victories which Father Ted helped win have made way for new controversies to divide the nation.

“It’s impossible to have a complete and honest human story if one doesn’t speak of human failings as well as human successes,” the recording at the beginning of “Hesburgh” concludes.

Combined, these two biographies offer a complete and honest human story, one prominently displaying the human successes while the other honestly chronicles the human failings. Read and watch them soon.