“We don’t know what we’re doing,” said G.K. Chesterton, “because we don’t know what we’re undoing.”

Historian Tom Holland’s new blockbuster, “Dominion” (Basic Books, $28.80) makes clear that what we’re undoing, in our current moment of cultural crisis, is Christianity. And yet Christianity stubbornly refuses to be undone.

Holland is known for bestselling histories of the ancient world. “Rubicon” (2003) is a dramatic account of the decline of the Roman Republic. “Persian Fire” (2005) tells the story of the Greco-Persian wars of the fifth century B.C.

In “Dominion,” Holland chases a much larger story: the entire 2,000-year history of Christianity. As the subtitle tells us, he intends to show “How the Christian Revolution Remade the World.”

Up front he states his ambition “to explore how we in the West came to be what we are, and to think the way that we do.” His thesis is that Westerners in the 21st century all think as Christians, whether or not they want to.

What interests Holland are ideas and their development. Intellectual history rarely makes for lively reading. But this author, who made his reputation writing military chronicles, knows that ideas have consequences. They play out on battlefields and in bedrooms. They move people to asceticism and assassination.

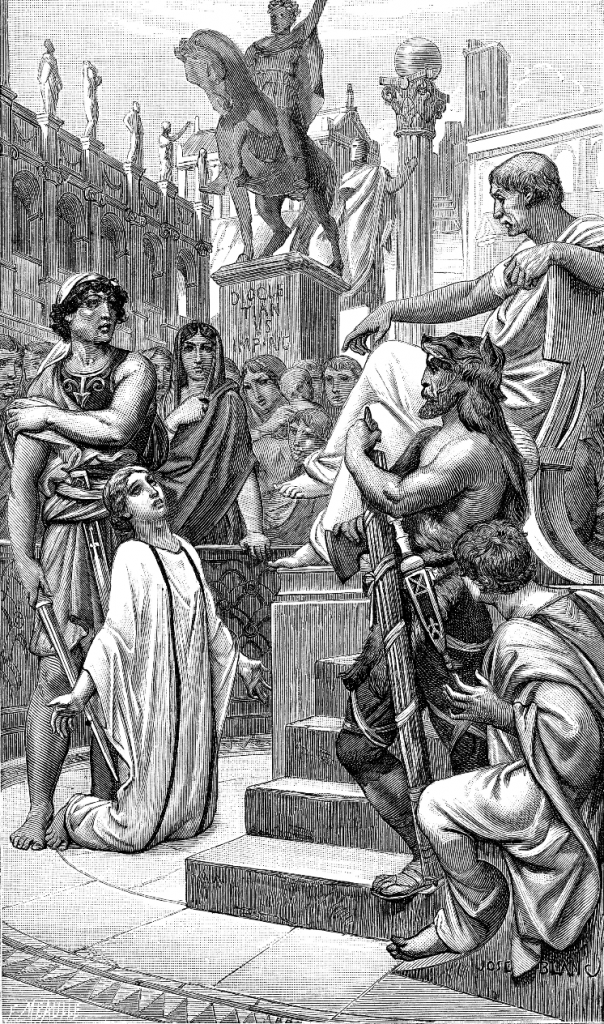

So the narrative of “Dominion” moves from one arresting scene to another. His discussion of Rome begins with a vivid description of the trash heaps where the city dumped the corpses of its executed criminals and used-up slaves. All were exposed to the ravening of scavenger birds and feral dogs.

What’s the point? To demonstrate the low value of human life in the pre-Christian world.

Holland’s tour of classical antiquity is more thorough than most. He introduces readers to the cultures not only of Greece and Rome, but also Persia and Babylon. He shows the cross-cultural consistencies: in sexual morality, in the way social classes were stratified, and in the vast gulf between rich and poor.

The ordering principle in every society was the same. “There was only the one timeless language: the language of power.”

Holland writes: “The heroes of the ‘Iliad,’ favorites of the gods, golden and predatory, had scorned the weak and downtrodden. So too … had philosophers. The starving deserved no sympathy.”

And elsewhere: “It was only by putting others in the shade that a man most fully became a man. … The future belonged to the strong.”

Power governed sexual relations. It was legal for masters to sexually use and abuse slaves, and slaves sometimes made up the majority of the population in these lands.

It was common for the rich to exploit the poor sexually: “Any man in a position of power had the right to exploit his inferiors, to use the orifices of a slave or a prostitute to relieve his needs much as he might use a urinal.”

Yet into this world Christianity arrived, proclaiming its God as one of life’s losers. Jesus had been executed shamefully, defeated, destroyed, and Holland emphasizes the “utter strangeness of all this, for the vast majority of people in the Roman world.”

For Greeks, Romans, and Persians, divinity “was for the very greatest of the great: for victors, and heroes, and kings. Its measure was the power to torture one’s enemies, not to suffer it oneself. … That a man who had himself been crucified might be hailed as a god could not help but be seen by people everywhere across the Roman world as scandalous, obscene, grotesque.”

Indeed, Christianity upended the values of the world by exalting weakness and poverty, and introducing novel ideas such as universal human dignity and equality. “If all were equally redeemed by Christ, if all were equally beloved of God, then what of the hierarchies on which the functioning of even the humblest Roman household depended?”

The Christian proposal was revolutionary, and the Romans recognized this, struggling intermittently to suppress it by means of persecution. But the more they made martyrs, the more attractive they made Christianity.

Holland tells the story of Blandina, a young slave in second-century Gaul, who endures days of public torture with heroic virtue. She is memorialized in Christian lore. And pagans marveled that “a slave, ‘a slight, frail, despised woman,’ might be set among the elite of heaven.”

In spite of its outlaw status, Christianity grew and, eventually, transformed the societies that had been its persecutors. The Emperor Constantine laid the legal foundations for a Christian empire, and rulers spent the next millennium sorting out how that might work. Not all experiments were successful.

Holland is unsparing in his description of atrocities visited by Christians upon their enemies. “I have sought,” he writes, “to evaluate fairly both the achievements and the crimes of Christianity.”

The most painful passages in the book are those that report the theological justifications for the battlefield slaughter of the Albigensian heretics in the thirteenth century, or the imposition of apartheid in 20th-century South Africa.

Yet, as Holland repeatedly shows, Christianity, unlike other historical movements, contains within itself the means of self-criticism, self-correction, and renewal. It is a quintessential Christian act to call for change. To speak of reformation, enlightenment, and revolution, the author explains, is “to dream in the manner of a Christian.”

“Dominion” traces through centuries the genealogy of ideas such as human rights. Holland shows the legal development of “rights” through the Middle Ages, and the ubiquity of the idea by the time of the Enlightenment. He also surveys the advance of the notion of the “secular,” first introduced by St. Augustine in the fifth century, as something distinct from the sacred.

That distinction became a full separation during the Enlightenment, as the Church was sundered from state and banished to a quiet corner of private life.

The state would, afterward, attempt to carry forward the project of protecting human rights, but without recourse to religion. For the American founders and European social reformers, “the surest way to promote Christian teachings as universal was to portray them as deriving from anything other than Christianity.”

But could the West sustain these ideas apart from their religious roots and theological justifications?

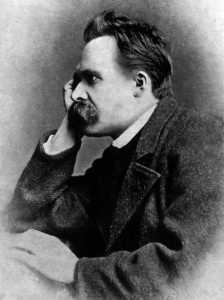

Holland introduces readers to two authors who scoffed at the very idea: the Marquis de Sade and Friedrich Nietzsche. For these men, says Holland, human rights “were nothing but flotsam and jetsam left behind by the retreating tide of Christianity.”

Holland observes: “More clearly than many enthusiasts for enlightenment cared to recognize, [de Sade] could see that the existence of human rights was no more provable than the existence of God.”

And Nietzsche derided “Such phantasms as the dignity of man, the dignity of labor” — “as if morality could survive when the God who sanctions it is missing.”

Holland sees the proof of these men’s claims in the rise of communism and Nazism in the 20th century.

In trying to advance the cause of human equality, the Soviet Union became “less a repudiation of the Church than a dark and deadly parody of it,” invoking historically Christian principles while killing Christians en masse.

The Nazis rejected biblical religion outright and sought a return to the pre-Christian standard of right, which is might.

Since the World Wars, elites in the West have continued to search for ways of establishing peace, of articulating a sexual ethic, of defining and defending rights. But still they lack a common language for the task, or even basic agreement about the goods they are pursuing.

He describes, in this context, the admirable, though frustrated, efforts of “Me Too” feminism and other contemporary movements.

Holland then draws a disturbing conclusion: “That human beings have rights; that they are born equal; that they are owed sustenance, and shelter, and refuge from persecution: these were never self-evident truths.”

He brings it home especially for Americans: “That all men had been created equal and endowed with an inalienable right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, were not remotely self-evident truths. That most Americans believed they were owed less to philosophy than to the Bible. … The truest and ultimate seedbed of the American republic … was the book of Genesis.”

And what of the future? “Whether this was an illusion, or whether the power held by victims over their victimizers would survive the myth that had given it birth, only time would tell.”

Holland’s book concludes with the story of his own loss of faith during adolescence. But he also recalls the intelligent Christian witness of his godmother.

At the end, he does not look to heaven for hope, but rather to the Christian past, which shows the faith to be resilient and infinitely capable of development, reform, and renewal.

He also looks to the family: “It was always in the home that children were likeliest to absorb the revolutionary teachings that, over the course of two thousand years, have come to be so taken for granted as almost to seem human nature.”