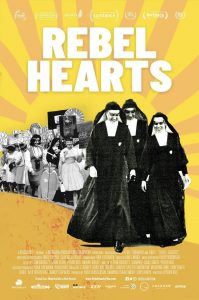

The new documentary “Rebel Hearts” has been promoted as the exciting story of Catholic sisters forced to battle “the patriarchy of the Catholic Church to fight for equality, their convictions, and livelihoods.”

While some people may be intrigued by this David versus Goliath story, it comes off as a superficial, one-sided account of the 1970 tragic breakup of the 600-member Immaculate Heart of Mary Sisters of Los Angeles (IHM), and offers no new insights on the 50-year-old story.

The sisters are depicted as heroines throughout the film: gentle, obedient, smart, and faithful in trying to follow the dictates of the Second Vatican Council (1962-65) to renew religious life.

The villain is Cardinal James F. McIntyre, archbishop of Los Angeles from 1947 to 1970, who is stereotyped as ultra-conservative, rigid, and vindictive. According to the “Rebel Hearts” script, Cardinal McIntyre wanted to control the IHM sisters completely, even telling them what to wear, when and how to pray, and what time to go to bed. And when the sisters tried to modernize, the cardinal “fired” them from the archdiocesan schools.

As with most conflicts, the true story of the demise of the well-respected Los Angeles IHMs is much more nuanced than the often-erroneous 1960s headlines that punctuate the documentary and seem to be the basis for the film’s script. While Cardinal McIntyre was known to be demanding, the leaders of the 300 sisters who left the IHM order were not the blameless victims depicted in the film.

To tell the story, writer/producer Shawnee Isaac-Smith and writer/director Pedro Kos rely heavily on the testimony of three of those former leaders: Anita Caspary (1915-2011) former mother general of the order who founded the secular Immaculate Heart Community; Helen Kelley (1925-2019) former president of now-defunct Immaculate Heart College; and Patricia Reif (1930-2002) a former philosophy professor at the college.

Some reviews of the film rave over archival video interviews of these and other former IHM sisters, which had been shot “over a 20-year period” by Isaac-Smith; but a major weakness in use of these videos is the notable absence of any date stamps. Thus, the viewer has no idea even in what decade the speaker was interviewed or that the person is now deceased.

The result is a shallow storyline that would have benefited from the guidance of a knowledgeable Catholic Church historian who could have corrected the misinformation in the film. For example:

- The IHMs were not a “cloistered” order; they were apostolic sisters who worked outside convent walls.

- Cardinal McIntyre did not “force” sisters to teach; their main apostolate was teaching, and they voluntarily came to California.

- The male hierarchy did not dictate customs and habits for women religious: Religious orders set their own particular rules. In fact, as early as 1950, Pope Pius XII had urged religious orders to modernize some of those rules.

- Orders of sisters did not teach “for free,” as the film reports. They were paid, albeit a meager salary, and usually they were provided with a convent by the parish in which they taught, and there were safety nets for health care.

- Sisters were not sent into classrooms fresh out of high school: They first had to complete a year of postulancy that often included teacher training, and one year of novitiate. It is true that sisters often began teaching without college degrees in the baby-boom years, but this also was true of lay teachers. The difference was that the sisters had a mentoring system in which veterans helped the rookies.

- The 1967 decision of the IHM sisters to make optional the habit, community life and common prayer, which were the foundations of religious life, was not in keeping with Vatican II documents or canon law, and a Vatican investigation confirmed the deviance.

- The IHM sisters were not “fired” from the schools by Cardinal McIntyre because they had reasonable objections to difficult teaching conditions; Mother Caspary withdrew them from the schools because Cardinal McIntyre wanted them to conform to Church law if they were going to be in the schools.

- It was not the women who left the IHM order who became penniless, as the film depicts: Mother Caspary’s secular Immaculate Heart Community was worth millions, for she had transferred all the IHM properties to the secular community, which also was a violation of canon law. Rather, it was the 54 sisters who chose to remain in the IHM religious institute in service to the Church who were left abandoned and without resources.

Additionally, the film suffers from important omissions. While repetitive archival videos of 1960s protests give a flavor of that era of chaos and widespread questioning of authority, there is no mention that the sisters participated in 1960s “sensitivity training” by psychologists Carl Rogers and William Coulson, and the results were disastrous.

Coulson, who came to regret his role because it caused so many religious orders to fall apart, told this reviewer in a 1995 interview: “We freed everybody from local doctrine. They were no longer constrained by rules because we persuaded them to make their own rules for themselves.”

Also, the film does not reveal much about the current state of the secular Immaculate Heart Community that Mother Caspary had envisioned as the ideal free way of living and working for justice. Her 2011 obituary reported 160 community members at that time. A community spokesperson in the film does relate that about half the members are “original,” which means half are at least 75 years of age, so its future seems tenuous.

Ultimately, “Rebel Hearts” fails by leaving the viewer with the impression that the number of sisters has declined (from 180,000 in 1965 to 40,000 today) because the Church put a stop to renewal of religious orders. In reality, the Church continues to urge proper renewal, and some orders have done so successfully, including the Immaculate Heart of Mary Sisters of Wichita, a teaching order founded in 1976 by three of the Los Angeles IHM sisters who continued to serve the Church.

The demise of so many orders of women religious actually was triggered in large part by the IHM “rebel hearts,” for many other orders followed their example and deconstructed the very elements of religious life that had attracted people who wanted to devote their lives to God through service in the Church.