So far, this has not been the retirement Archbishop Charles J. Chaput had in mind.

The emeritus archbishop of Philadelphia was looking forward to reading, writing, and making up for some of the sleep missed over the course of his 32 years leading three U.S. dioceses as a Catholic bishop. And since handing the reins to his successor in Philadelphia, Archbishop Nelson Perez, early last year, he has had plenty of time to do those things — perhaps too much time, even, thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic.

One fruit of that extra time is “Things Worth Dying For: Thoughts on a Life Worth Living,” (Henry Holt & Co., $22) a wide-ranging personal reflection on the meaning of life published this month by Henry Holt and Co.

The Kansas native is no stranger to conversations about death. His father was a mortician and embalmer. Two years after becoming Archbishop of Denver, he was called to help heal a grieving community in the wake of the Columbine massacre. And in his more than three decades as a bishop, he became one of the universal Church’s most eloquent critics and commentators on the perils of the “culture of death” in America and throughout the West.

Today’s world, he argues in the book, traps us “in a permanent present, a narcotic cocoon of distractions and appetites” that “steals the memory of who we are as Christians and why we’re in the world.” To respond to this, Chaput believes, we must reclaim a Christian sense of purpose and destiny beyond ourselves.

In our Zoom interview from his residence in suburban Philadelphia, Chaput spoke about a range of topics, from the consequences of the Second Vatican Council to the personal friendships that have sustained him during ministry, and why he asked for a speedy replacement upon turning the mandatory retirement age of 75 two summers ago.

Archbishop, in this new book, you go from talking about death and the Psalms, to the Song of Roland, to modern cultural trends like the video game Fortnite. So it is a bit difficult to categorize, or describe in a single sentence. What is this book about, and why did you write it?

It was my agent, Bill Barry, who suggested I write a book with reflections written in my old age about what I see going on in the world, our country, and in the Church.

I focus a lot on death, the fact that we're all going to die, and that then we're going to be judged at the time of our death. And the results of that judgment are going to be either heaven or hell. So what are the things in our lives that help us to end up in the right place, in the right relationship with God?

I talk in the book about some of the important motivating forces that help us live good lives, the things that we think are worth living for, which are often what we believe are worth dying for.

I'm not naive. I think a lot of us say we’d die for things and then in the end we wouldn’t. Like the protagonist in the movie “Silence,” a Jesuit who, while everyone else in the movie was willing to die for their faith, in the end he was not. Many of us would have probably ended up the same!

So my book is an invitation for others to join me in reflecting on the important things that I've discovered in my 76 years that are worth living and dying for.

So is this what retired bishops do when they retire? Think more about death and the last things?

As you get older, you naturally start to think about death more than before.

It’s interesting: In this last year of the pandemic I've slept more than I have for years. Now I’m getting seven hours of sleep a night. Before retirement I used to sleep six hours at most, getting up early to pray and working as long as I could.

I’ve noticed that my dreams now are more vivid and maybe because I'm more relaxed, but they're often dreams about the past, about my parents and my early relationships in life. I didn’t used to remember my dreams and many of them are now just going back over the past and reflecting on the good things that happened.

So I started doing that more than just this last year. I've been thinking about my life a lot in maybe the last five or six years more than before.

You know you’re not the only one, right? A lot of people have written about how their dreams have gotten weirder and more vivid during the pandemic.

Well, mine haven’t been so much weird, but they’ve been vivid and I do remember them!

There’s a chapter in your book where you compile answers to questions posed to some of your closest friends, and to yourself. Among the topics you discuss is the Second Vatican Council. At one point you say that as chaotic as the situation of the Church seemed after the Council in the 60s and 70s — around the time when you were ordained a priest — you think the situation is even more serious now. If you could go back in time, what would you say to your newly ordained priest self?

I think the Second Vatican Council is the most precious gift that the Holy Spirit has given the Church in my lifetime. I was ordained a priest in 1970, so the last part of my seminary formation was very much influenced by the Council, and I'm grateful that I was exposed to all the documents of the council while I was still in school.

I suspect many priests who were older than I am probably didn't even read them. I think it’s really unfortunate for the Church, because a lot of things were claimed by others about the Council that weren’t true.

I think that, like many at the time, I was too optimistic about the impact of the Gospel on the world around me. I thought that if we proclaim that Jesus resurrected from the dead and glorified in a very friendly way the world would follow quickly and submit themselves to Christ in his teachings. And that didn’t happen. The reason things are much worse today is that the culture in which the Gospel is preached is much more difficult.

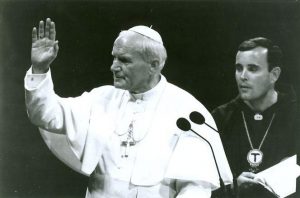

When St. Pope John Paul II came after the Council and proclaimed a new springtime for the Church, I was confident that under his leadership the springtime would come. And it has, but for many fewer people than I expected.

It is true that those who are serious about the Church are living the Gospel more intensely and with greater integrity today than they did in the 50s, 60s, and 70s, and 80s even, as the world around them is going in a different direction.

I thought the Protestants, Catholics, and Orthodox would come together, that we’d have a common face, for example. Mainline Protestantism has all but evaporated in terms of fidelity to their principles and their theology, while evangelical Christians seem much more strongly committed.

It’s true, there’s a certain friendliness between ourselves and the Orthodox today that wasn’t present back in the 60s. But it hasn’t led to the kind of union that Jesus prayed for, that we would be one as he and the Father are one.

On top of that, the Catholic world is also very divided.

I do see many [Catholic] young people who are still getting married and developing families, for example, so that is a blessing.

But [the last 50 years] sure haven’t worked out the way I thought they would.

Archbishop, I want to take a break from your book for a moment. After you submitted your required letter of resignation to the Holy Father upon turning 75 back in 2019, you were pretty vocal about wanting a successor to be appointed as soon as possible. Why?

I was sent to Philadelphia at a very difficult time, both in terms of priest sexual abuse issue, and then the major financial problems we discovered. We worked hard to get all those things into a balanced state, and I think that I accomplished that.

But then it was time for the Church to recommit herself to the future, and I knew that unless I was going to have a longer period of time than just a year or two, I couldn’t do that. Leadership requires time, and it requires the collaboration of people who aren’t really willing to commit themselves to you if they don’t think you’re going to be around. So I thought it was important for the good of the Church in Philadelphia to begin its own springtime, to have a leader in place who could do that for a significant amount of time. Why waste the Church’s time by waiting for a couple of years where you’re kind of a lame duck with nothing going on?

So I actually went to see the Apostolic Nuncio, Archbishop Christophe Pierre, before my retirement date to encourage him to find a replacement for me as soon as possible. He was very helpful, and I was replaced within a few months of my 75th birthday.

So that’s the background. I wasn’t tired and it wasn’t because I was depressed. It’s just that I thought the church in Philadelphia needed leadership for the future and I just couldn’t do that because of my age.

You ended up handing over the reins to your successor, Archbishop Nelson Perez, just a few weeks before the COVID-19 shutdown happened. What do you make of that timing?

I feel sorry for the Archbishop, because he had only had about three weeks before the closure. He’s been here now for about a year and it hasn’t been a normal year.

People ask me how I think he’s doing, and I always say, give the man a chance to really show that when he has freedom...and then see what kind of energy he brings to the local Church.

The COVID environment is just not a place to begin a ministry. He says he’s fine and he feels good about it, and he’s made the best of the past year and he does get around despite the lockdown. But it isn’t the same.

Can you share any advice that you gave Archbishop Perez when you retired?

I actually didn’t give him any advice because I think that can be torture to a new bishop, because he wants to find his own way.

He and I do talk on the phone a lot. I always tell every bishop to trust the Holy Spirit and also to work hard at collaboration between the laity and the clergy.

It seems to me that you let the Holy Spirit control things and you have to step in if there’s people that step out of bounds, but it is important to encourage creative and enthusiastic lay leadership and the development of new charisms.

It seems like a lot of the things going on in America right now were things that you anticipated in your writings and speeches over the last decade, like “Strangers in a Strange Land” and “Render Unto Caesar.” Where is the U.S. right now as a country?

Back when I wrote “Render Unto Caesar,” in which I talk about the place of the Church in a pluralistic society, I was more optimistic about the Church being successful in that task than has proven the case.

It seems there is real danger to religious freedom now and in our country — mostly because people aren’t serious about religion or religious freedom.

The United States was founded by Europeans seeking religious liberty. It was a very important issue for them, even though they didn’t really recognize the liberty of Catholics at first, or the liberty of slaves, in the first decades of our country.

You’re going to have a difficult time if you don’t respect the dignity of every individual. Today, we don’t have any respect for the dignity of the unborn as a country. When you don’t do that, you begin to embrace ideologies that enable us to interfere with the order of creation, like gender theory.

Likewise, if we don’t respect the elderly, which we don’t, then we embrace things like euthanasia. Things can turn pretty bad pretty quickly and I worry about that.

This is going to sound a little bit political, but it seems strange that the best we can do as a country in terms of leadership were the options we had for president in the last election. Neither of those were very good, objective options in themselves. Like, is this the best we really could do? It’s just a strange time.

In your past books, speeches, and writings, you’ve always seemed particularly interested in American history and our roots as a country. In this book, you return to that theme, particularly the thinking of Alexis de Tocqueville. How has your thinking on that subject evolved in the past few years, and is America worth dying for?

I believe that our fellow citizens are worth dying for, and that we have to be willing to lay our lives on the line for them.

In my generation, we were all raised to believe that military service was a noble thing and now it’s seen as a fearsome thing. It’s as if they don’t see our country as having any virtues that would be worth dying for. That’s something to be afraid of now, I think.

You mentioned De Tocqueville. He was a very interesting man. He actually saw our country from an outside point of view, but I think the criticism he made about the dangers in America and American thinking could happen, in which unbridled democracy can lead to the abandonment of principles. So I would say that I worry about the future of our country in a way that I didn’t worry about 10 years ago.

I developed that interest in our country’s roots because I began to worry about religious freedom and the loss of commitment to our founding principles. And I thought that my contributions might help change that. I don’t know that they have, but we’ll see.

Archbishop, switching gears again. You seem more engaged in the culture than, say, the average bishop.

Maybe it’s just because I talk more than the others do.

Maybe. But I know you spent a lot of the last year working on this book. What else have you been doing during your COVID-19 retirement?

I actually have discovered television. There are really some extraordinarily good shows that have been produced over the last 30 years that are really interesting. I’ve watched many more videos this last year than I have in the last 30.

I like British detective series. Some of them aren’t very good, but there’s one called “River” that is extraordinarily interesting.

I’m a science fiction fan and so I’ve watched the new version of Battlestar Galactica. And I’ve gone back to watching some old movies that I’d forgotten, like “The Silence of the Lambs,” which is one of my favorites, as well as “A Man for All Seasons” and those kinds of classics.

I read a lot. I try to have a biography, a novel, and a kind of book about the natural world going at the same time. Right now, I’m reading a book about human bones.

I’ve read books on beards, insects, on trees, and the history of chickens even. I also try to do a significant amount of theological and philosophical reading, mostly in journals. And I have read a good share of spiritual books over the course of the last year as well.

So I read, I pray, and I cook, and I think. I also do spiritual direction on FaceTime and in person. But I’m looking forward to getting out and around soon, and going back to doing parish work on weekends and things like that.

In the last chapter of your book, you make the case for authentic friendship as an overlooked but essential part of Christian life. What are some examples of that kind of friendship in your life?

Well, the book is dedicated to the “Sams” in my life. Samwise Gamgee from “The Lord of the Rings” is the traveling companion of Frodo. And I’ve had a lot of friendships that are like that one.

When I was in Denver, I would host a monthly dinner in my home for a group of friends where we would solve all the problems of the world and the problems of the Church over good wine and a good meal. The religious Sisters of Mercy were wonderful in helping me host by preparing the meals.

Some of those people were the leaders of many of the significant Catholic movements in the Denver area. Some of them have gone elsewhere now in recent years, but those movements are really important.

I also belong to a bishop’s prayer group. We haven’t met this year because of the lockdown but we hope to get together sometime in the spring.

But my friendships have been very limited because of COVID-19. I visit with family and friends by FaceTime and on the phone, but I haven’t really been able to be with my friends over the course of the year very much.

Hope is also a theme in your book and especially when you’re talking about heaven. That’s what you seem to conclude is the greatest thing worth dying for. But what is it that gives you hope for the Church itself right now?

Jesus gives me hope, because he is the reason we hope. Hope is confident in the future because we trust God. I don’t know what that future is. I thought I did know it in ways that I obviously didn’t.

For example, I thought Vatican II would be much more fruitful immediately and it hasn’t been. I think it will be in the long run. I thought the reforms of John Paul II and Benedict XVI were going to be hugely effective, and they’ve kind of fallen apart over the course of the last several years. But in the end, the only true source of hope is Jesus and his Resurrection from the dead.

And we’ll let God take care of the details about how we get from here to there, but I know we’re going to do that because we have God’s promise that it’s going to happen.

And I also am stirred to hope by the young Catholics that I meet who are enthusiastic about the Gospel, you know. They’re sinners like the rest of the Catholics, but there’s a kind of energy and commitment to the truth that is beautiful. And it always gives me hope. And I see that in the seminarians that I meet these days.

So we still have a lot of energy in the Church because that energy is the Holy Spirit. And the Holy Spirit always wins in the end.