From “Star Wars” to “Superman” there are Christ figures everywhere in pop culture

There’s not always a lot of room for Jesus in today’s pop culture scene. But if you look closely at some of our favorite stories of superheroes, science fiction, and fantasy, you find Jesus hidden throughout, in stories of good and evil that are played out on the big screen and in books.

I sat down with James Papandrea, author of “From Star Wars to Superman: Christ Figures in Science Fiction and Superhero Films” (Sophia Institute Press, $15) to discuss our obsession with these stories of fantasy and supernatural, and what we can learn from them.

Kris McGregor: Why are these stories so important to so many people?

James Papandrea: The story isn’t really about science or technology, it’s about bigger questions. What does it mean to be human? What does it mean to have free will? What does it mean to be morally responsible for our choices?

People who say they aren’t into sci-fi don’t get this, but it’s not about the gadgets and the futuristic technology so much as it is about these big questions.

McGregor: The stories that stick with us are the ones that respond to that inner longing to have these philosophical explorations in our hearts. Do you think people realize that?

Papandrea: One of the things that science fiction and superhero stories acknowledge is that, to put it in a Christian context, humanity is fallen, and we need help. The question becomes: What kind of help do we need? Do we need a savior? Can we save ourselves? And then the writers try to speculate about the answers.

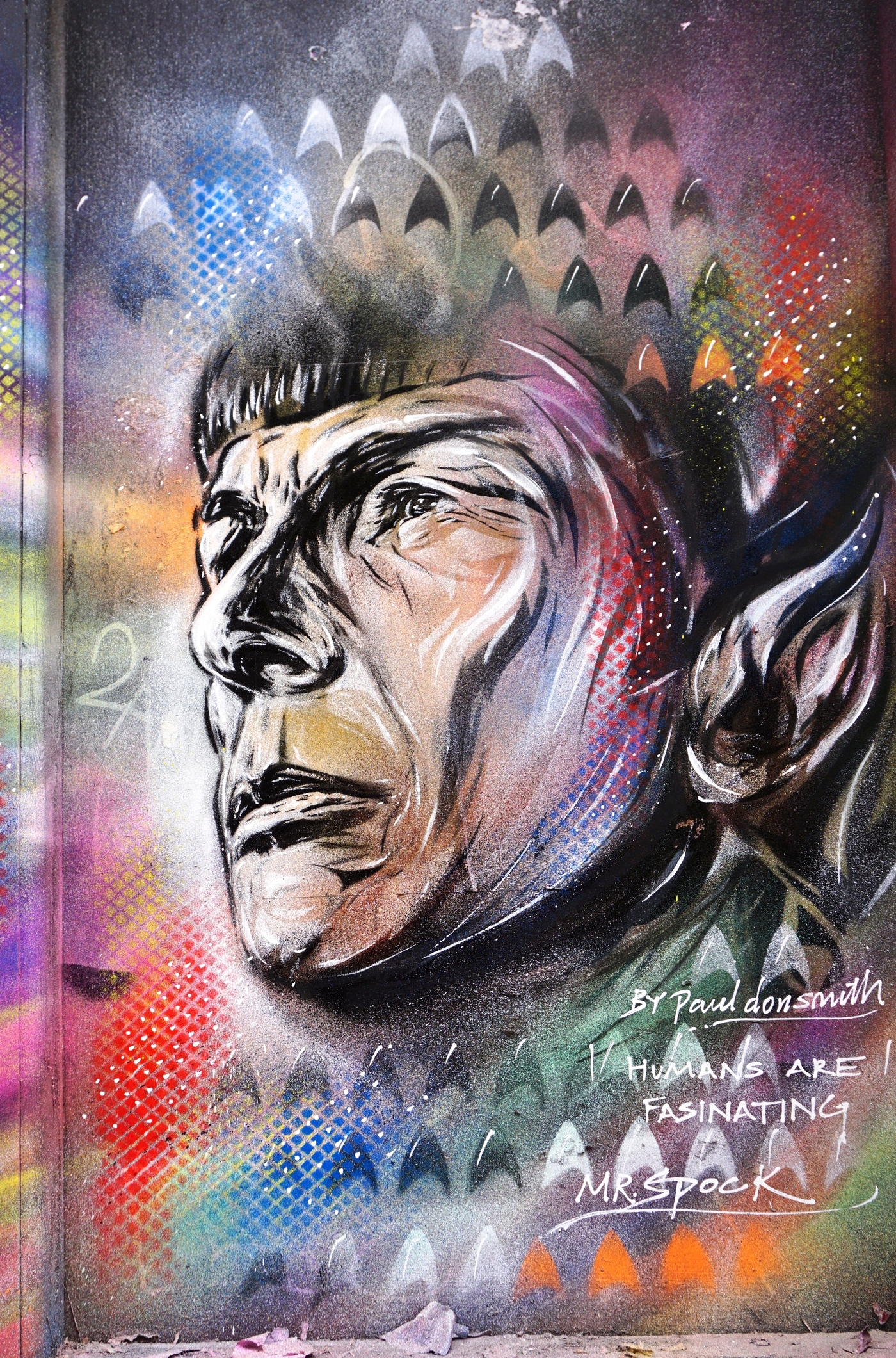

McGregor: My husband still remembers when he watched “Star Trek” as a kid.

Papandrea: For many of us, that’s one of our first exposures to sci-fi. The original “Star Trek” has been a constant throughout our whole lives, and there’s a lot of good in that, but then there’s some problematic things in terms of the assumptions that underlie the stories. We need to go into these stories with our eyes open and critique the things that contradict our faith.

McGregor: In the first seasons of “Star Trek,” they’re trying to find out why man is good, why we’re called to be out there. They’re seeking a greater goodness. But then it kind of slides into the Arianism heresy, doesn’t it?

Papandrea: In the quest to find goodness in humanity, they ended up trying to convince us that humanity is the greatest good, and that was their problem. Gene Roddenberry envisioned a utopia in which humanity had outgrown religion, based on the assumption that religion holds us back from realizing our potential as a human race.

So in “Star Trek,” that must mean an outgrowing of faith, to the point where we’re so enlightened that we don’t need it anymore.

There’s one episode, “Rightful Heir,” where they’re talking about a Klingon savior figure, and the tagline is, “Perhaps the message is more important than the man.”

What they’re trying to do here is present the idea that what Christ said was good, but it would be better if you could detach it from the man Jesus, and have it be in the abstract. I got to interview the writer, and he pretty much confirmed that! This is the message, and it’s classic Arianism.

The savior — it’s not about him. It’s about his message and the example he sets. If you can follow his example and his message, that would be salvation.

The problem is that’s really self-salvation. Our faith teaches that we can’t save ourselves. No matter how hard we try, we’ll never be that good. We’ll never follow Jesus’ example perfectly enough to earn our own salvation. The message is really about the man.

McGregor: “Star Wars” seems like a simple story of good and evil. But there’s a dark hole it goes down when it comes to understanding good and evil.

Papandrea: Star Wars gives you a universe where good and evil are kind of equal opposites that need to stay in balance. The ultimate goal isn’t the triumph of good over evil, but the balance of the Force. And once you start making balance the ultimate good, then you’ve turned evil into a necessity, a good. Good and evil lose all meaning.

McGregor: It’s not the dynamic of good and evil that we understand as Christians.

Papandrea: Good and evil aren’t equal opposites. Evil is the rejection of all the good that God has created. That boils down to the choices that individuals make with their free will.

But a lot of sci-fi turns evil into this kind of big-picture injustice, which loses the reality of personal sin. In contemporary culture, that’s very consistent with the idea that there is no such thing as personal sin. It’s relativism — what’s right for you might not be right for me. It lets us off the hook for our own personal sin.

McGregor: These stories tug at our emotions. But they challenge us, too. They make us think about who we fundamentally are as people with faith in Christ.

Papandrea: I love these stories. And I want other people to love them too, but I want people to love Christ more, and to recognize when some of these stories present messages that we should explore and critique. These movies can be springboards for some really great evangelization.

Kris McGregor is the founder of Discerninghearts.com, an online resource for the best in contemporary Catholic spirituality.

SPECIAL OFFER! 44 issues of Angelus for just $9.95! Get the finest in Catholic journalism with first-rate analysis of the events and trends shaping the Church and the world, plus the practical advice from the world’s best spiritual writers on prayer and Catholic living, along with great features about Catholic life in Los Angeles. Subscribe now!