There is a scene in Ken Russell’s film of The Who’s rock opera “Tommy” that depicts a church whose goddess is Marilyn Monroe. In a grotesque mockery of Catholic devotion, the faithful rise from their pews to venerate a larger-than-life porcelain statue of the actress, while preacher Eric Clapton croons that she “gives eyesight to the blind.”

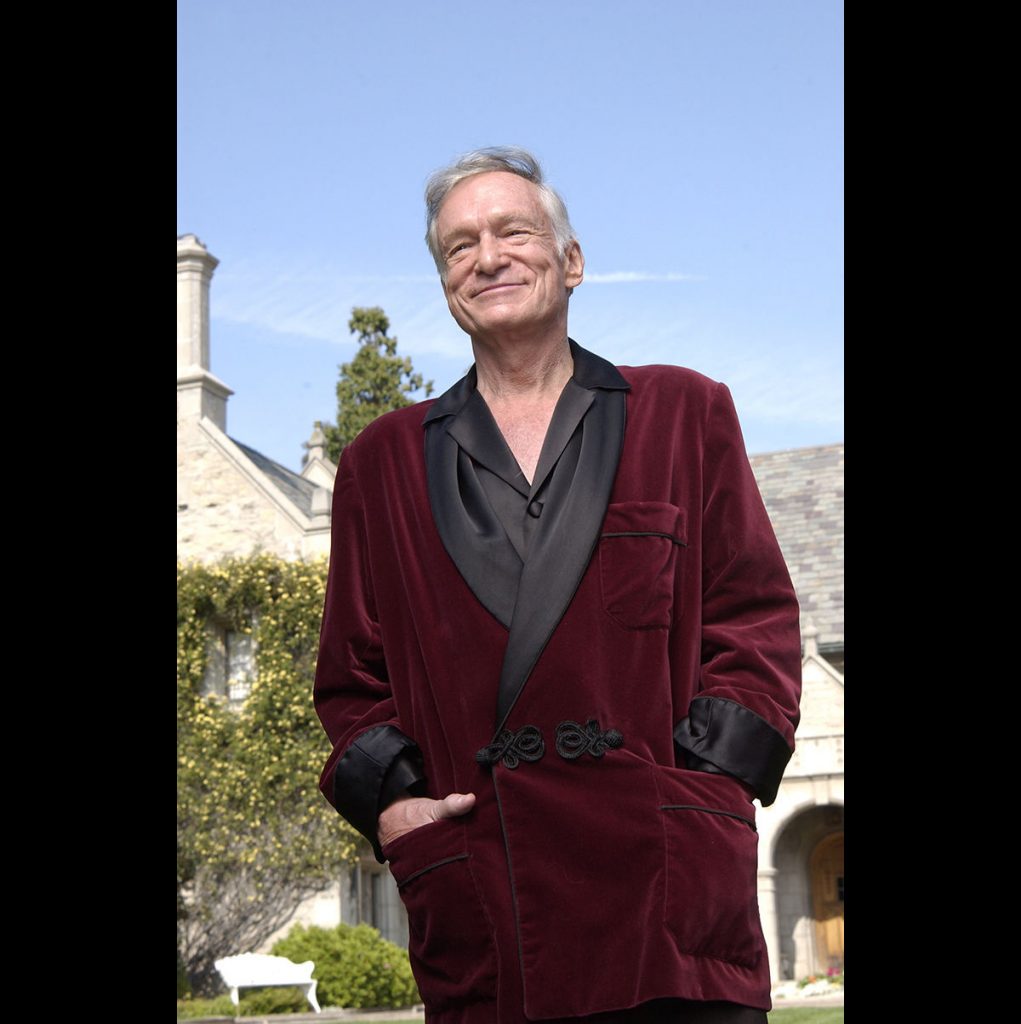

I thought of that scene when I learned that Hugh Hefner, the Playboy magazine founder who died Sept. 27 at the age of 91, paid $75,000 in 1992 to buy the vault next to Monroe’s at Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery in Los Angeles so that he could be buried next to the ill-fated star.

Hefner made the purchase because, as he told the Los Angeles Times, he was “a believer in things symbolic.”

“Spending eternity next to Marilyn,” he added, “is too sweet to pass up.”

Where Hefner may, in fact, be spending eternity is not for me to say. But he was right to recognize the symbolism in his desire to enjoy the afterlife in the presence of Monroe, whose nude image (published without her consent) was the major selling point for Playboy’s premier issue in 1953.

The symbolism has to do with the fact that Hefner, in a kind of perversion of the Christian ideal, saw himself as having undergone two births. The first was his natural birth, whereas the second was his personal re-creation as the founder of the Playboy empire, of which, he told The New York Times, “I have … created my own world on my turf and terms.”

Now, in Hefner’s mind, Monroe was linked to both his births. “I feel a double connection to her,” he told CBS Los Angeles in 2012. “She was the launching key to the beginning of Playboy [and] we were born the same year.”

In a sense, then, Hefner not only made Monroe his final end; he also designated her as his first cause. It was too little for him to cast himself as the pajama-clad messiah who would save America from its Puritan past. He also had to, like Jesus, choose his own mother.

It could be said, in charity to Hefner, that in selecting Monroe as his origin and destination, he was acting out of one of the deepest desires known to man: to spend one’s entire life in beauty, surrounded by it and suffused with it.

That is, in fact, not only a core desire of the human person; according to St. Augustine, it is also a core desire of the angels. St. Augustine tells us that the angels, upon their creation, were immediately faced with a choice. As they entered into their first moment of consciousness, in which they recognized that they were suffused with the divine light, they had the option of either basking in their own beauty — navel-gazing, we would say — or looking beyond themselves to the unsurpassable, capital-B Beauty of their Creator.

All of the angels had the opportunity to make this choice with full knowledge of the consequences. Having the benefit of angelic intellects, they, unlike us, were naturally smart enough to recognize without hesitation that they could not have created themselves.

Most of the angels chose to cooperate with the divine light they were given, and so they turned to God — following the trail of beauty from themselves to their divine source. But some — one-third, according to a traditional interpretation of Revelation 12:4 — chose to rest in their own created beauty. The moment they made that choice, they severed the thread of grace connecting them with their Maker and so cast themselves into the abyss — thereby losing the very spark that fueled their dazzling luster.

When the news broke about Hefner’s chosen resting place, some feminist commentators complained that the Playboy mogul continued to exploit Monroe in his death just as he had done so during his life. Regardless of what one may think of feminists’ agenda (which corresponds with Hefner’s own more than many of them might care to admit), in that respect they were absolutely right. Hefner, like the fallen angels, wanted beauty — but, as he said, on his own “turf and terms.” So he made Monroe his personal creator goddess — her own will and desires be damned.

To be fair to Hefner, he is far from the only person who seeks to grasp beauty rather than reflect it. Spiritual directors note that insecurity — which in itself is but a form of pride, for it avoids trusting in God — is often at the root of the temptation to lust. C.S. Lewis was frank about this in a letter to a friend. He wrote that “the real evil of masturbation would be that it takes an appetite which, in lawful use, leads the individual out of himself to complete (and correct) his own personality in that of another (and finally in children and even grandchildren) and turns it back, sends the man back into the prison of himself, there to keep a harem of imaginary brides.”

Hefner did all he could to make that “harem of imaginary brides” real. He even extended his prison of himself into a mansion, with a bedroom full of mirrors so that his lived fantasy might appear to extend into infinity. But “in the end,” Lewis adds, the imaginary women — and in Hefner’s case, I would say, the real ones, too — “become merely the medium through which [the individual] increasingly adores himself. … After all, almost the main work of life is to come out of ourselves, out of the little dark prison we are all born in. … The danger is that of coming to love the prison.”

Hugh Hefner loved his prison so much that he tried to put the whole world inside it. Now his body is in a different kind of prison — a marble vault next to that of a woman whose beauty, which so captivated him, has long turned to dust. As Catholics, we can pray that his soul may be free to enjoy the vision of true beauty. But there remains for us the longer and more arduous task to work and pray to free, by God’s grace, the countless men and women he has left captive to his Playboy philosophy.

Dr. Dawn Eden Goldstein is an assistant professor of dogmatic theology at Holy Apostles College and Seminary and, as Dawn Eden, is the author of several books.