This Macbeth is the story of a man’s deal with the devil, told in dramatic strokes of black and white.

When Joel Coen decided to direct “The Tragedy of Macbeth,” he knew he faced a dilemma. Should he work hard to make it as un-play-like as possible? Should he switch every soliloquy to voiceover, with footage of mountains and heather and skulls underneath? The only other option, it seemed, was to do something stiff and stagey.

But Coen decided there was a third way, reasoning that, after all, all the world’s a stage. “The Tragedy of Macbeth,” in theaters since Christmas Day, exists in a misty half-abstract space, full of stark black lines and pale castles looming through swirling fog. Such effects give a film the quality of a dream, an opaque and fantastical land where fell spirits lurk in every bog and hollow. Everything looks a bit like a set, but never feels set bound, its surreality giving our imaginations space to fill in the blanks.

The film’s cinematography is a unique achievement, giving it both great beauty and an elemental power. And its simplicity makes us zero in on language and characters, allowing the moral arc to come to the fore. By the end of the film, there’s no doubt that the “tragedy” portion of the title is clear. We are left mourning Macbeth’s deal with the devil.

To refresh your memory, Macbeth is the story of the original medieval Bonnie and Clyde, a couple who go on a murder spree to obtain and secure the throne, only to find that “Nought’s had, all’s spent / Where our desire is got without content.”

Macbeth, in his madness, carries out tyrannous purges of those he deems disloyal, driving shrewd nobles to flee to England. Meanwhile, the insanity of Lady Macbeth (played by Coen’s wife, Frances McDormand) ends not in egotism but in self-annihilation. Following Macbeth’s cruelest massacre, the exiled nobles rally for a climactic confrontation in which the very forces of nature will rise to oust Macbeth.

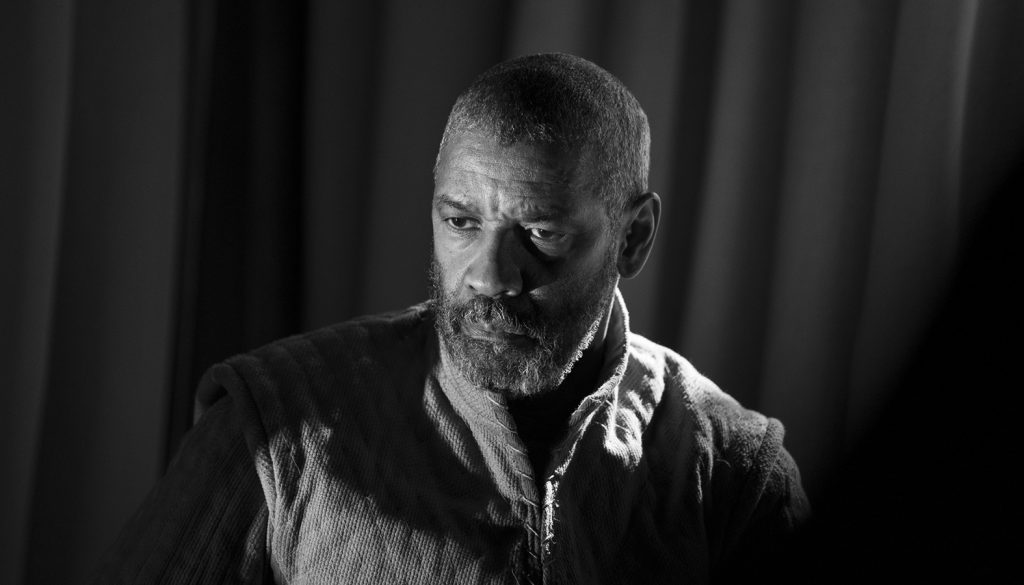

Much has been made of the fact that both McDormand and Washington are older than the Macbeths of ages past. Washington’s hair is brushed with silver, lending him the weary dignity of a lion in winter. Their marriage is one old and settled, a husband and wife “contra mundum” (“against the world”), more friendly than romantic. Childless. This change alters the Macbeths’ motivation from dynastic hopes to a final desperate power play.

“He wants what he’s due; he’s overdue,” Washington said of the character in an interview on The Late Show. And thus Macbeth dove “into the dark side. He listened to the devil.”

Washington’s career as an action star in recent years gives him credibility as a bloody pagan warrior, tormented by the pangs of a Christian conscience. (University of Virginia Professor Paul Cantor argues that Macbeth, like Hamlet, is the story of a man and a country torn between antithetical ideologies, those of Christian England and pagan Norway.)

“Are you so gospeled,” Macbeth disdainfully asks of men in whom he’s trying to arouse resentment, “to pray for this good man and for his issue / Whose heavy hand hath bowed you to the grave / And beggared yours forever?”

Early in the play, Washington plays the wicked Thane as listless to the point of passivity, a sometimes alienating choice. But when Macbeth’s ego is emboldened by his nihilistic murders, Washington’s virtues become very apparent. He is more a movie star than traditional Shakespeareans like Ian McKellan or Paul Scofield — giving a naturalistic performance infused with characteristic dignity, earnestness and star charisma.

Rather than embracing the delirious madman stereotype, Washington plays Macbeth as a nihilistic ubermensch, totally convinced of his invulnerability, numbed to his sins. Tormented at first by scrupulosity, his conscience is quickly seared and his deeds become more and more depraved.

When a prophecy reveals to Macbeth that he can never be defeated until a forest comes to his castle, he responds, “That will never be. / Who can impress the forest, bid the tree / Unfix his earth-bound root?”

Of course, Macbeth was thinking too figuratively — it ends up being an army that looks like a forest. J.R.R. Tolkien found this twist a cop-out, and “fixed” it by writing into his magnum opus “The Lord of The Rings” a scene with a fortress overthrown by walking trees. Coen also leans towards the fantastical, envisioning the very forces of nature arising to topple Macbeth from his bloodily won throne.

By far the film’s greatest achievement, however, is its entrancing production design, which revives the German Expressionist imagery typical of German cinema in the 1920s and 1930s. Its beautiful, unexpected imagery nimbly reinvests the Weird Sisters with their ability to terrify, aided by Coen’s choice to discard any sort of Halloween-ish witch cliches in favor of simple, black-robed figures. Evoking Death from the Ingmar Bergman film “The Seventh Seal,” they perch like vultures on the beams of Macbeth’s castle. An initial appearance by a contortionist witch (Kathryn Hunter plays all three witches and a mysterious old man) is particularly striking.

“Macbeth” is a movie that looks like nothing else in theaters today, vividly and boldly showing that simplicity doesn’t have to mean bland minimalism. That it feels comfortable telling a dark story in such beautiful, careful images shows that it rejects its protagonist’s nihilistic excess (an interesting contrast to the ugly vividity of another medieval 2021 A24 film, “The Green Knight”).

“The Tragedy of Macbeth” isn’t perfect. The first act lags, and the choice to have the actors speak the lines naturalistically and quickly sometimes means that the words sound like so much noise (sound and fury, even), when they should signify something. But once it kicks into gear, it’s a gorgeous and compelling piece of work, easily my favorite film of 2021.