One of the most painful aspects of our country’s ongoing border crisis is the sheer number of children who are detained without their parents. While many Catholic bishops describe our immigration system as “broken,” I don’t think the trauma hidden in it is sufficiently addressed.

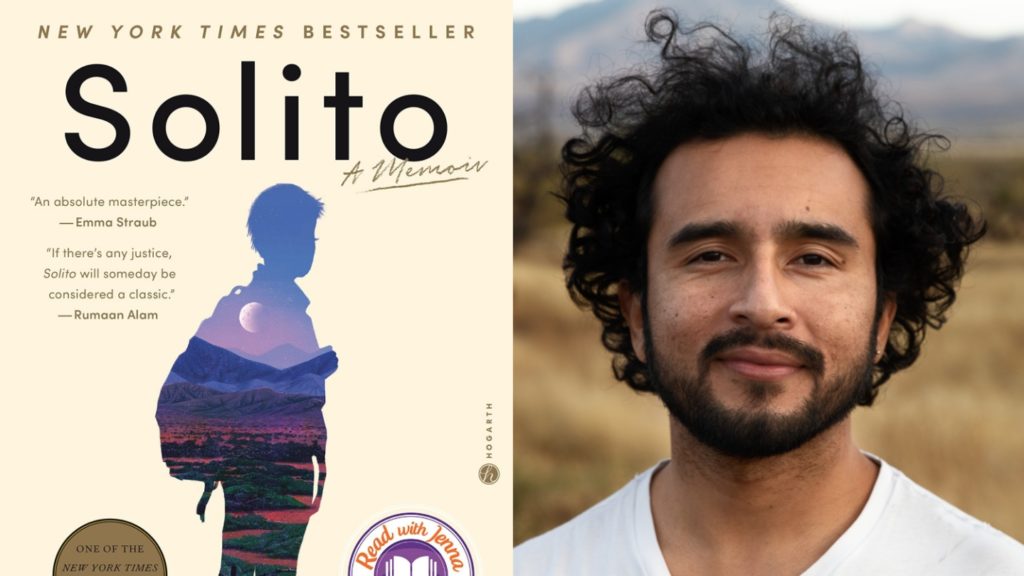

Why are children found at the border without their parents? For me, Salvadoran American poet and activist Javier Zamora’s book “Solito” (Hogarth, $19.95), “Alone” in English, or given the diminutive, perhaps better translated as “All Alone,” offered some important insights.

Officially described as a memoir, it is more of an autobiographical novel. Zamora’s eloquent account of his nine-week journey to the United States at the age of 9 years old was written with the help of a therapist who helped him to remember details of the experience. The text bears signs that we are dealing with a kind of recovered memory process, which is not without certain problems.

The author confesses that he still faces some effects of the trauma surrounding his undocumented entry into Mexico and the United States. The account of his path through the desert of Sonora is especially harrowing by itself. But as the story of a child traveling with strangers to reunite with his parents in California, it is an Odyssey-like epic of memories both poignant and painful.

Zamora’s experience is a key to understanding the problem of the undocumented immigration of minors. His parents were in the United States for several years and wanted their son with them. He was being raised in a small fishing village on the Pacific coast of El Salvador by his grandparents and aunts. For years he heard that one day he would make a “trip” to the United States.

His attempts to get a visa from the U.S. Embassy failed. Then came talk of traveling under an assumed name and passport. Finally, his family turned to “Don Dago,” (pronounced “Dahgo”) a “coyote,” someone who arranges undocumented entry into the United States.

All this makes for an intense reading experience, one that may make you feel, as I did, that you have entered the mind of a 9-year-old child as he faces the strangeness and painful hope of getting to his parents in the land of his dreams.

His idea of the United States, or “La Usa,” was quite different from the reality. Zamora was so traumatized by the experience of being a “mojado” (a commonly used term that means “wet one,” perhaps a reference to those who crossed the Rio Grande River without papers) that he still questions whether the trip was worth it. In his acknowledgments at the end of the book, he assures his parents that he has “already” forgiven them. This was necessary, perhaps, because he said they never knew some of the details of his experience until the book was published.

Again, this book is a reconstruction of his journey. A narrative of events can never be completely accurate. But the book is convincing, and reminds me of something Nobel Prize winner Mario Vargas Llosa said in his book “La Verdad de las Mentiras” (“The Truth of Lies”) (Alfaguara, Spanish, $21.88), about how fiction, although sometimes a form of lying, speaks the truth.

Some years before writing “Solito,” Zamora published a book of poems called “Unaccompanied” (Copper Canyon Press, $15.99) about his experience. There are some contradictions between the poems and the narrative of “Solito.”

In the prose work, little Javier meets up with a mother, Patricia, her daughter, Carla, and their friend, a man called “Chino” (a common nickname in El Salvador). They become his family during the difficult travel by bus, boat, vans, and foot. Chino carries Zamora for part of the trek in the desert. At the end of “Solito,” the author says he has no idea where Chino is presently. He also claims to have no memory of the man calling his parents when Zamora first arrived in California.

But in “Unaccompanied,” a poem dedicated “to Chino,” he explains that he was killed in Virginia by a rival gang from El Salvador. In the “memoir,” it says Chino has a tattoo but nothing else; in the poem, the tattoo denotes affiliation with the notorious street gang MS-13.

Obviously, you can decide to leave out information in the sometimes-exhausting catalog of sights, sounds, and smells experienced during a two-month, 3,000-mile journey. However, if Chino was a gang member, it would make his nobility with Javier more outstanding and his personality more interesting.

So, did the poem or the memoir tell the truth about the man, or just partially or neither? Readers may never be sure, but perhaps that’s part of the point here: “Solito” is a window to the experience of millions of people who now live in our society.

Zamora expresses so much that we should be aware of: their desperate hope; the lonely longing for home and family; the dangers; the hunger, thirst, and frightening encounters with the soldiers and law enforcement; the clandestine hideouts and jails; the fear of dogs and guns and helicopters; the friendship their common fate engenders and the corruption and deception they are exposed to; and the aching fear of being caught or even dying on the way.

All of these human aspects lie underneath real political, social, and economic issues. They demand our recognition and sympathy. Reading “Solito” was an emotional gauntlet that at times shocked me, made me laugh and tear up, and even want to pray as I turned the pages.

“Solito” should be required reading, at least for priests in “La Usa” — not only to better understand the crisis at the border, but also in light of a new Pew Research study showing a 24% drop in identification with the Catholic Church among U.S. Hispanics. We are losing our own.