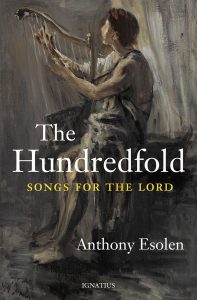

Jane Greer interviewed Anthony Esolen by phone about his new book, “The Hundredfold: Songs for the Lord” (Ignatius Press, 2019, $15.26). Some of his remarks appear in this review of his book.

“Let’s suppose you have in your attic 200 original great paintings by the masters,” says Anthony Esolen. “Most of them are religious paintings — by Rembrandt, Raphael, Titian, Angelico. They’re up there! Aren’t you gonna go up there and take ’em out and look at ’em? Wouldn’t you do that? I think you would do that! Because it’d be crazy not to!”

We have the equivalent of that attic, 2,000 years’ worth of Christendom’s magnificent poetry, and we seldom visit it. “Why? It’s all ours, there for the taking,” Esolen says. “I’m hoping to get Christians in general, and Catholics in particular, to take back this art.”

Esolen is a renowned Catholic scholar, speaker, teacher, and author of more than 700 articles and two dozen books of translation, scholarship, and social commentary. He’s a tireless champion of scriptural fidelity and imaginative writing as he takes to task insipid modern hymns and adulterated Bible translations.

What many of his readers may not know is that he’s also a gifted poet who for 30 years has channeled his considerable poetic muse into other work. With this book, he at long last offers us his own poetry again.

But “The Hundredfold” is not just a book of poetry, and not just social or liturgical commentary. It’s all that and more. It actually demonstrates what it encourages: reclaiming the literary bounty that belongs to us as human beings, Christians, and Catholics.

Monumental in almost every way except for its physical slenderness, the book comprises an introduction and a poem, “The Hundredfold.” The introduction is a gentle poetry primer. It also explains in detail the poem’s extraordinarily complex organization, comprising 100 smaller poems on various scriptural themes.

There are 67 lyric poems, 12 long dramatic poems in blank verse, and 21 hymns. The organization of styles, stanzas, and lines as they tell the story of our faith is mathematically intricate — think “The Name of the Rose,” by Umberto Eco.

Not everyone will be interested in admiring the poem’s architectonics, but any reader can enjoy the meaning and the sound. Esolen’s scholarship is towering, but it doesn’t get in the way of goodness and beauty. Still, the complexity mattered to him: He created the poem’s outline and planned most of the parts and arrangement before ever starting to write.

“For heaven’s sake, why?” some might ask, and the answer is: for heaven’s sake. “Poets in the Middle Ages and Renaissance — Dante, Petrarch, Spenser, Shakespeare — wrote like this all the time,” he says.

“The idea was that God created this cosmos in ‘measure, weight, and number’ ” (Wisdom 11:20. God made language but also made math, science, and music. “Artists took it for granted that they should try to reflect that order. … Art is a reflection of the power and glory of God.”

But that was then. Today, many Catholics — many Americans — do not love or appreciate poetry. Schools no longer teach either poetry or much history, ignoring the marvelous heritage of poems from the past.

The most recent century is filled with “free verse” that does little with sound and is almost uniformly secular, even though, as Esolen writes, “the most exalted themes for the music of man have always been religious, in a broad sense.” The result of all this is that for perhaps the first time in history, many people feel no connection to poetry.

This makes Esolen come undone. “Poetry is dynamite! You don’t have to spend three weeks reading a 600-page novel. You could spend five minutes reading a great poem. And a poem will be with you for the rest of your life, maybe, if you commit it to memory. It’s concentrated power.

“If you’re trying to form your children’s imaginations and you’re not using poetry,” he says, “it’s like you’re trying to dig a tunnel through a mountain with picks and shovels and you won’t use dynamite. Use the dynamite!

“There’s no reason why poetry has to be so far removed from the ordinary experience of people. It never used to be that way. What I really want to do is to write for fairly intelligent people who would be willing to read a poem — my fellow believers. I’m writing for them.”

As an example, here’s lyric poem 26, whose epigraph is Exodus 20:19: “Let not God speak with us, lest we die.” The Israelites were afraid of the thunder and lightning, and blew “shofars” (“horns”) from the smoking mountain where God waited.

They wanted Moses to be the go-between because they were too fearful of God speaking directly to them. There’s a vast difference between the “they” in the first line and the “we” in the second line, between then and now — and someone is watching.

“They dared not look upon Him, lest they die.

But we go blandly past Him all day long,

Or what we vaguely fable in the sky,

Daddy who shakes his head when we do wrong,

And sighs, and shrugs, and hums a little song,

Something with faith and flowers and heaven in it.

Not grandly evil, only small and vile,

We seek our pleasure till the latest minute,

Sinning away in soft assurance, while

Satan observes us with a frozen smile.”

In the U.S. today, Catholic churches are nearly uniform in limiting their music to 10 or 20 songs written in the past 50 years. From antiquity to the 1970s, a hymn has always been understood as a song praising the greatness of God. Modern “hymns” focus instead, to a large extent, on making us feel happy.

In his book, Esolen calls it “the severe constriction of mood: the songs at their best and most innocent are fit for happy children clapping their hands in a kindergarten jingle. At their worst they are sickly sweet songs of self-celebration for sinners not desiring reform or the terrible soul-cleaving power of love; or they are political slogans, as ephemeral as last week’s newspaper, though not so good for lining a bird cage.”

The old hymns, from the early Fathers of the Church to the early 20th century, “were always talking about the Trinity. They were always talking about the Word made flesh,” Esolen says. “It’s pretty high theology. It never focuses on the feelings of the singer. That would have struck them as kind of beside the point.”

Here’s hymn IV, for which Esolen suggests the tune “Picardy.” (You may know the tune as “Let All Mortal Flesh Keep Silence.”) He writes his hymns to fit the tunes, and once you’ve read — or sung — this hymn to this haunting tune, any other way will feel wrong.

“From the desert came the sages,

Crossed the Jordan in the cold,

With the star of Judah gleaming,

Making straight the way foretold;

Found the Child and gave in homage

Frankincense and myrrh and gold.

From the desert of Judea

Came the prophet’s piercing cry,

Calling sinners to the waters

Of the Jordan rushing by,

That they might be found preparing

For the Savior drawing nigh.

Unto John then came our Savior,

In the fire of righteousness;

Dove-like, brooding on the waters,

Fell the voice from heaven to bless;

Then the most beloved Messiah

Fasted in the wilderness.

Come to us then in the desert,

Where Thy sheep have lost their way,

Lost the pasture by the river,

While the lion stalks his prey;

In the trackless night, O Savior,

Be Thyself our break of day.”

In the Bible, a hundredfold refers to receiving in return much more than has been given, sown, or invested. Esolen wants us to rediscover our powerful birthright of poetry — that dynamite! — and experience the hundredfold return of joy and faith. He wrote this book “as a first salvo in the Christian reclamation of the land of imagination and song.”

“I am not so much showing what I can do as showing what can be done, and what might be done by people with greater skill than mine. I want not emulators and imitators but people who will charge past me in blood and triumph.

I am a battered old soldier on bad knees, who knows that the hill must be charged and who knows of one or two ways it might be done. He takes up the torn standard of the cross and hobbles up the first reaches of that height, crying out instructions that he himself has not the strength to fulfill, teaching more by audacity and exposure than by success, willing to look like a fool, to be shot down in the first volleys, but knowing that unless he or someone like him does this, the hill will remain always in the fist of the enemy.

So he goes.”