Much of what we “know” today about the inner workings of the Second Vatican Council is thanks to a mischievous priest.

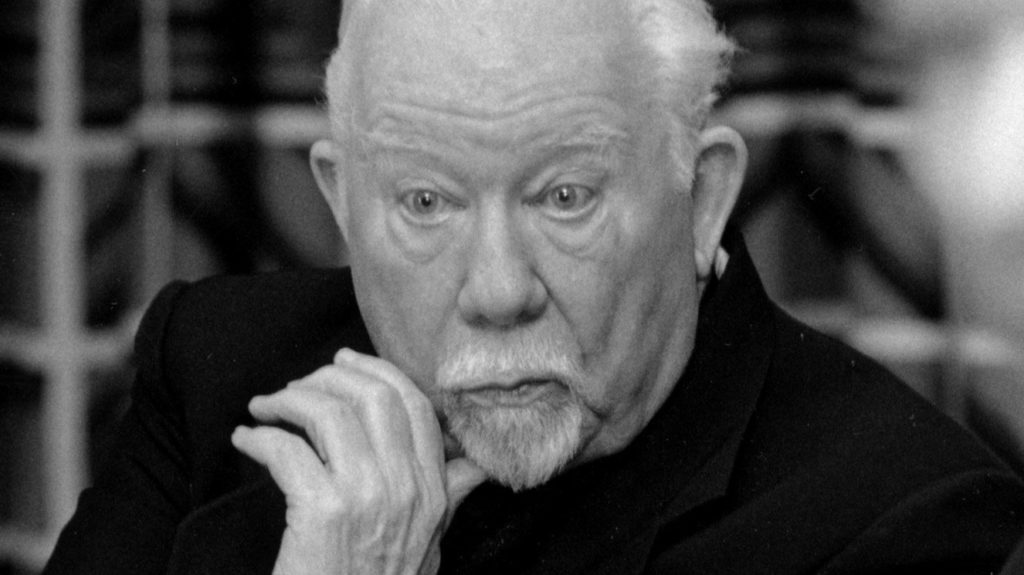

Father Francis Xavier Murphy, C.Ss.R, was a “peritus,” or theological adviser, to an American bishop at the council. He was also a talented journalist and wrote about the Council for the New Yorker under the pseudonym Xavier Rynne (his middle name plus his mother’s maiden name).

Rynne’s “Letters from the Vatican” gave “a gossipy but engrossing account of what was going on” at the council, in the words of one Church historian. His inside scoops were unique and controversial, stirring the anger of Vatican officials who had imposed a vow of secrecy about council proceedings on participants. (Similar restrictions were also in place at the most recent synod gathering in Rome, but with apparently more success.)

Murphy did not come clean about being Xavier Rynne until late in life, and that was because he did not want his heteronym to be claimed by the “damned Jesuits.” I think there was more to it than that, and I understand his nostalgia for an exciting time in his life and that of the whole Church.

His nostalgia prompted him to confide in a layman, Richard Zmuda, who helped him write an introduction to an edition of his New Yorker pieces published in 1999. This year, he published “The Mole of Vatican Council II” (ACTA Publications, $29.95), a work Zmuda says “should be considered historical fiction” that draws from Murphy’s extensive personal correspondence, travels to Rome, perusal of various secret files kept on the priest, and his own close personal relationship with his novel’s protagonist.

Why Zmuda decided on writing a novel about Murphy subtitled “The True Story of ‘Xavier Rynne’ ” is puzzling to me. Much of the book reads like a history, albeit simplified and not immune from the label “tendentious.” He sees the Second Vatican Council as a kind of ecclesiastical version of the movie “High Noon,” with his hero fighting alone against the evil cardinals of the Roman Curia.

The chief villain is the arch-conservative Cardinal Alfredo Ottaviani. Then the head of the Holy Office (now known as the Dicastery of the Doctrine of the Faith), he is depicted with so much antipathy that this reader began to sympathize with the supposed ogre. An outspoken critic of some of the ideas that surfaced during the council, Ottaviani’s episcopal motto was “Semper Idem” (“Always the same”). Zmuda reports this as a kind of “Aha!” detail without mentioning that the phrase is scriptural, referring to “Jesus Christ, the same yesterday, and today and forever” (Hebrews 13:8).

In a speech at the council’s first session, St. Pope John XXIII said that “the great problem addressed to the world, for almost two thousand years, remains unchanged. Christ, radiating at the center of history and life; and men, either with Him and the Church … or … without Him or against Him.” That seems like pretty binary and old-school thinking to me.

Zmuda is no theologian, which is no crime, but that should have made him hold back on some sweeping statements about history. He seems to believe that the Council of Trent “resulted in the cataclysmic split of the Protestants away from the Roman Catholic Church, including the eventual formation of the Lutheran, Reformed, Presbyterian, Anglican, and other Christian denominations.” You cannot cause something ex post facto.

Several times he implies that Pope John XXIII was against the ecclesiastical use of Latin. He forgets that, after the call for the council had already been made, the pope wrote an apostolic constitution, Veterum Sapientia (“The Wisdom of the Ancients”), which stated, “the Latin language, by its nature, is perfectly adapted to all forms of culture en all peoples: it does not inspire envy, is impartial with all, is no one’s particular privilege and is well accepted by all. We cannot forget the Latin language has a noble and characteristic structure, and a concise, diverse, and harmonious style that is majestic and dignified, especially suited for clarity and solemnity.” According to a former seminary professor, theological instruction was mandated in Latin by Veterum Sapientia.

When Zmuda lets the liberal (good)-conservative (bad) trope rest, he ventures into some strange territory. The fictional Father Murphy has his own bank accounts, likes to eat and drink at fancy Roman restaurants, and keeps his fat checks from The New Yorker for himself (in defiance of his vow of poverty).

He is enamored of a wealthy Italian aristocrat (with whom he is pretty up close and personal) and contemplates violating his vow of chastity with a waitress that he flirts with in front of a bishop. To complete the trifecta, he lies to his superiors and hierarchical figures (which would be against the vow of obedience, according to some people I know in the Midwest).

The two women, Cristina and Luciana, are “composite characters,” he says, “invented by me but are considered essential to the authenticity of the overall storyline.” That is a curious statement to make, but I confess that, for me, the book’s only element of suspense comes from the priest’s relationships with the two femmes vitales. I held my breath reading how the priest and the waitress dine on the rooftop of a ritzy hotel, before the cleric stops the elevator on a floor where he has rented a room. (Spoiler alert: the canny working lady quickly punches the button for the lobby and the priest stares as the doors close on her descent.)

The book jacket describes the “novel” as a “timeless and timely thriller.” Needless to say, I was happy to finish reading the thing, but far from thrilled.