In 1970, at the height of their fame, The Band was on the cover of Time magazine when that meant something. One by one, right up to last month, each member of the extraordinary quintet passed away, felled by alcohol, drugs, cancer, and suicide.

With the Jan. 21 death of multi-instrumentalist Garth Hudson — age 87, the organist and grown-up of the group, the only one granted a peaceful death — all are gone from this sphere if not the radio.

Now and then you’ll hear the “Up on Cripple Creek” on an oldies station. Other times, independent radio will air all five-and-a-half minutes of “The Weight,” known via the chorus “...take a load off Fannie.”

Born in Windsor, Ontario, in 1937, Hudson grew up and was classically trained in nearby London, all long before there was such a thing as classic rock. His star turn is the Lowrey Festival organ introduction to “Chest Fever,” a song that runs five minutes and 18 seconds on vinyl.

Onstage, the intro alone could go as long as eight minutes. Grounded in Anglican liturgical music and Baptist hymns he played as a kid at his uncle’s funeral parlor, it’s an operatic swirl of Bach, church music, and whatever happened to be firing behind the virtuoso’s wide, curved brow any given evening.

“Garth’s organ playing is the secret sauce of The Band,” said Peter Aaron, arts editor of Chronogram in the Hudson Valley where Hudson lived in Woodstock for the past 50 years. “The colorful little sprinklings and hues and countermelodies he weaves throughout the songs makes The Band sound different from the other groups of their day.”

To quote Nathaniel Hawthorne, Garth's work “...breathed passion and pathos, and emotions high or tender, in a tongue native to the human heart.” He did so before tens of thousands when The Band accompanied Bob Dylan on his 1974 “Before the Flood” tour and, as the decades and spotlight faded, a few hundred fans at small venues like Cheek-to-Cheek Lounge — now a drug store — in Winter Park, Florida.

It was there in March of 1986 that pianist and plaintive vocalist Richard Manuel played his last show, thanking Garth after “for 25 years of incredible music.”

Manuel, 42, hung himself with his belt in the predawn hours the following day, abetted by despair and bottles of Grand Marnier, in the bathroom of a nearby Quality Inn, an alcoholic unable to reconcile past greatness with the present.

Bassist Rick Danko died in 1999 at age 55 from heart failure exacerbated by drugs and alcohol. Drummer, vocalist, and mandolin player Levon Helm — born in Turkey Scratch, Arkansas, in 1940 — died in 2012 from throat cancer. Guitarist and primary songwriter Robbie Robertson, 80, died of prostate cancer in 2023.

Aside from autobiographies by Robertson and Helm, the primary resource for what these men achieved and how they did it is “Across the Great Divide: The Band and America” (Hal Leonard, $30), a 1993 book by the journalist Barney Hoskyns.

In a 2002 interview, Hudson gave one of the best descriptions of the way music is transformed — The Band a prime example of all strands of Americana — when filtered through the people playing it.

“Different musical styles are like different languages,” he said, fluent as well on accordion and any saxophone he cared to pick up. “It’s all country music; it just depends on what country we’re talking about.”

The country that Hudson explored in 1980 was Los Angeles by way of the empyrean. It was the city’s bicentennial year and he provided the soundtrack to a massive installation by designer and native Angeleno Tony Duquette.

Duquette (1914-1999) called work inside the Museum of Science and Industry at Exposition Park “The City of Our Lady Queen of the Angels on the river Porciúncula.” It included eight 28-foot-tall archangels, a quartet of altars to the elements, and bejeweled tapestries.

Hudson released the music independently on cassette and gave it the same name as the installation. You’d have to be a very ardent follower of his work to know it was him or even know it exists. Upon careful listening — ethereal organ spiced with the chirping of birds, Garth on trumpet and vocals by his late wife Maud — it becomes clear.

Like myself, many fans of The Band and of Hudson had never heard of it until he passed. In the comments section of a video of the album one posted: “May Garth rest in the peace of Christ with Our Lady and the angels…”

A tinker of sound, Garth Hudson was known by insiders as “Honey Boy” for the sweet touches he added to The Band’s music in the studio, on stage, and in post-production. He was the guy who recorded, compiled, and edited songs from 1967 of Dylan and The Band known as “The Basement Tapes” released in 1975.

He was born Eric Garth Hudson on Aug. 2, 1937, in a family that identified with a nonconformist Christian movement known as the Plymouth Brethren, an early 19th-century Irish offshoot of Anglicanism. (Volunteers from the group’s Rapid Relief Team recently assembled in LA during the wildfires and fed firefighters and rescue teams thousands of meals.)

His mother, Olive Pentland Hudson — whose accordion Garth began playing at 12 — was said to be a strict adherent to the Brethren, who hold that the Bible is the only authority on worship and doctrine. His father, Fred, a farm inspector and drummer who also played flute, saxophone, and piano, helped his only child rebuild two pump organs. Both parents sang and the family spent hours together listening to the radio.

To pacify his parents, when Hudson joined a band that played in nightclubs, honky tonks, and roadhouses, he said he was giving the boys music lessons. In many ways, they learned from him to the end.

Loquacious only on an instrument, more is known about Hudson’s thoughts on music than his religious beliefs — though the two merged seamlessly anytime he sat down at a church organ.

I happened to be riding a cargo ship in the North Atlantic when Garth Hudson died on the feast day of St. Agnes. It was organ music I heard — as expansive as a basilica — while saying a rosary for his soul at the Cathedral of Our Lady in Antwerp a week later, the feast of St. Thomas Aquinas.

As I sat for an hour or so before returning to the ship, Mass began. While I don’t understand Flemish, my Catholic muscle memory led me through the celebration by way of cadence.

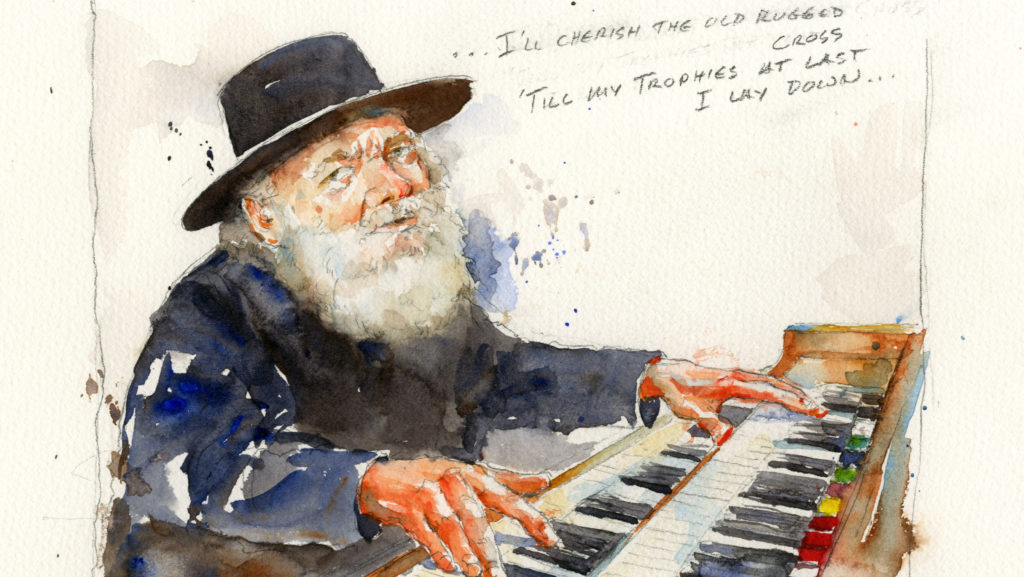

Taking my place in line, I received the Eucharist for the soul of Hudson, a man I’d never met, somehow knowing he wouldn’t mind. His last performance was sitting in a wheelchair at a piano in the nursing home playing and singing The Old Rugged Cross.

“I will cling to the old rugged Cross

And exchange it some day for a crown …"

After the last note, he says, “Yeah, that’s a good ole tune…”

Hudson was mourned during a service at the Old Dutch Church in Kingston, New York, on Jan. 27. He is buried nearby at the Woodstock Artists Cemetery.