Like many millennial women, I spent my teenage years wanting to be Rory Gilmore, the daughter on the popular dramedy “Gilmore Girls” from the early Aughts. Rory was the first intellectual, literate teen character that popular culture served up to us.

In her valedictorian speech from her fictional preparatory school, Chilton, Rory describes how the characters in the catalog of great books were steady companions and mentors, such as those in William Faulkner’s “As I Lay Dying,” Marcel Proust’s “Swann’s Way,” and Herman Melville’s “Moby Dick.”

Now that I am a mother, I think a bit more about Lorelai Gilmore, Rory’s mother, whose academic career was disrupted by her teenage pregnancy. In one episode, she expressed to one of her beaus that she, too, hoped to read more of the greats:

“I’ve never read Proust. I’ve always wanted to. Every now and then I’m seized with the overwhelming urge to say something like ‘As Marcel Proust would say,’ but of course I have no idea what Marcel Proust would say, so I don’t even go there. I could do, “As Michael Crichton would say,’ but it’s not exactly the same, you know?”

Lorelai never gets around to cracking open the greats, mostly because her life is always a bit chaotic. She’s often depicted flipping through women’s magazines and engaged in constant cordless phone chatter (the source of dopamine hits before the iPhone was created).

Preoccupied with work deadlines, caring for young children, and managing our home, in the early years of my married life, I set aside hopes to read the great books that I had collected while single. They seemed to taunt me from my bookshelves. I understand Lorelai’s plight as a working mother.

If I did find time to read, I prioritized nonfiction books about timely cultural topics or the news. Both paid dividends for work. Everything in those years was aimed at efficiency and productivity.

While that type of reading kept me abreast of cultural trends, the constant barrage of news and commentary, even in long form, was draining. I needed to find time to read fiction, books that served no practical purpose.

I also knew that it would be hard to hold myself accountable. Stay-at-home moms continually see their homes in disarray. There is always something to be picked up or wiped down.

To make things worse, turning a blind eye to check phone notifications and resisting the urge to periodically check Twitter (X) would require outside incentives.

It was providential, then, that at that time I was invited to a book club with women from my parish who were going to be exploring some of the great Catholic writers.

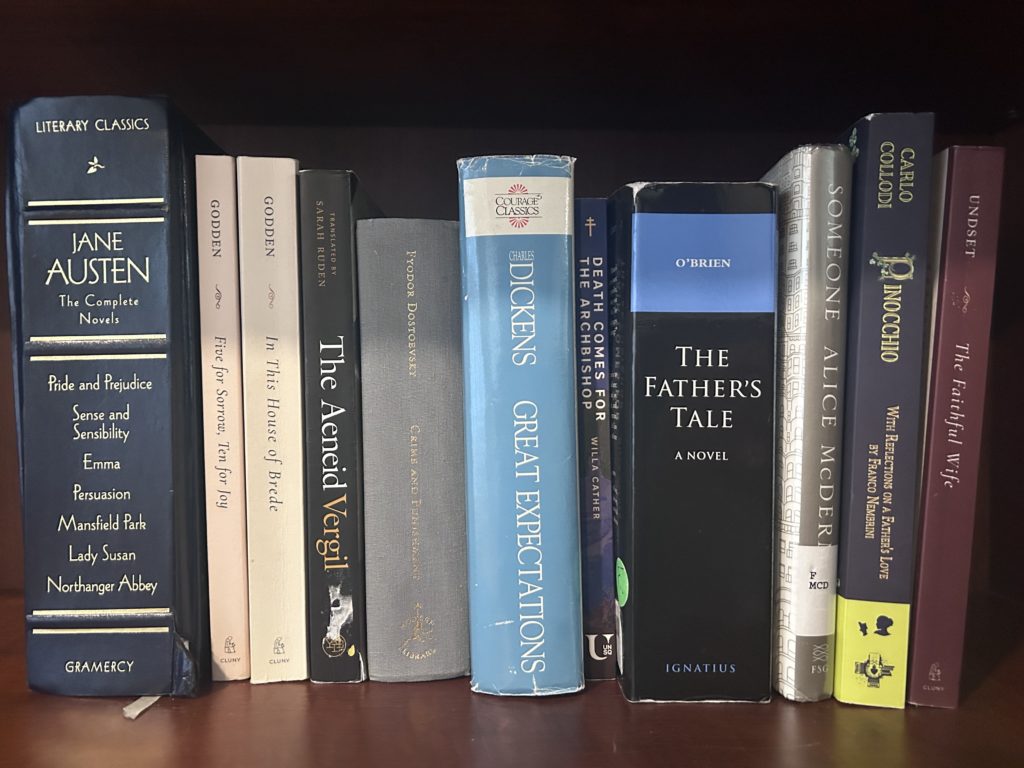

Joining was one of the best decisions I’ve made. Three years in, I’ve explored sin and the human condition with Graham Greene, in the “End of the Affair” and “The Power and the Glory”; examined what makes for a troubled marriage with Francois Mauriac’s “Thérèse,” and peeked inside the convent with Rumer Godden’s “In This House of Brede,” and “Five for Sorrow, Ten for Joy,” among others.

The practice of reading fiction, traveling to faraway places, and meeting characters well outside of my day-to-day encounters made me think of St. Thérèse of Lisieux. Though the Little Flower was confined to her cell as a Carmelite, she saw herself as a missionary, able to bring the Gospel to the ends of the earth through her prayer.

I began to realize that as a mother, reading fiction was a way to be transported beyond the laundry room and nursery, if only I set aside just a few minutes a day. Far from an escape, it has changed the way I look at my tasks, considering more closely the people I’m serving, just as I closely examine the characters in these fictional worlds.

The experience was so enriching that I joined a second book club this year — a local chapter of the Well Read Mom group. Founded by Marcie Stokman who “learned that she was a happier, more whole woman, wife, and mother when she was reading good books,” the program asks participants to commit to one book a month and offers guides for discussion and supplemental reading material, all based on a theme.

To date I’ve discussed the theme of fatherhood illustrated in such works as “Cry the Beloved Country” by Alan Paton, “Peace Like a River” by Leif Enger, and the 1,000-page tome “A Father’s Tale” by Michael O’Brien. It has given me rich material to reflect on my gratitude for my relationship with my own father, the many priests in my life, and my husband’s love for our sons.

Meeting book club deadlines has taken some creativity. I bring the book to physicians’ waiting rooms and pull it out of my diaper bag in the line at the grocery store. I’ve also been so far behind schedule that I’ve woken up at 5 a.m. for a whole week just to get in reading before my kids get up. My husband jokes that I look like an undergrad cramming for a final.

My reading has benefited my family, first in the conversations that I have with my husband, who is also committed to reading fiction, but also because my sons see me read. This is a tried-and-true way of helping pre-readers get interested in books.

It’s also enhanced my empathy. As I encounter different characters, I think about how my sons might turn out, or what challenges might be ahead for me or my loved ones.

This was the insight of another leading lady, not on television but on the front lines of revolutionizing care for the poor.

Dorothy Day was a huge fan of fiction. In the introduction to “The Long Loneliness,” Day’s autobiography, Robert Coles, a former Harvard professor, recounts bringing students to meet her in the mid-1970s.

When asked what she wanted to be remembered for, she included that she loves books and recommended the greats, like Tolstoy and Orwell, to others. “That’s the meaning of my life — to live up to the moral vision of the Church, and of some of my favorite writers.”

“When I die, I hope people will say that I tried to be mindful of what Jesus told us … and that I tried to take those artists and novelists to heart, and live up to their wisdom (a lot of it came from Jesus, as you probably know, because Dickens and Dostoevsky and Tolstoy kept thinking of Jesus themselves all through their lives).”

This is what I have found — good fiction is an examination of the human condition. And since mothers are in the business of forming humans, what better teachers are there than the greats?

To every mother, I urge you: read novels, even for 15 minutes a day. You’ll also feel like a human again.